Gunther Schuller: "I Am the Eternal Student"

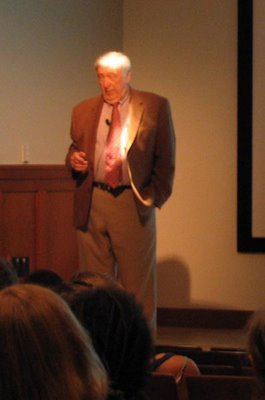

Last year, American composer Gunther Schuller -- an American institution unto himself, who has won both a Pulitzer Prize and a Grammy -- turned 80 years old. After being honored with a series of concerts in Boston (covered by Frank Pesci for Ionarts), he showed up here in Washington at the Library of Congress to accept the honor of being named a Living Legend. Thursday night he was back, this time at the Phillips Collection, as part of the museum's latest Artful Evening, to draw attention to its most recently opened exhibit, Paul Klee and America. This took place in the fancy new auditorium in the museum's renovated wing, a nice place to hear a lecture but not yet without some technical kinks. After extensive pre-lecture sound checks, which held up a sizeable crowd from entering, there was still feedback during the introduction of the speaker.

Last year, American composer Gunther Schuller -- an American institution unto himself, who has won both a Pulitzer Prize and a Grammy -- turned 80 years old. After being honored with a series of concerts in Boston (covered by Frank Pesci for Ionarts), he showed up here in Washington at the Library of Congress to accept the honor of being named a Living Legend. Thursday night he was back, this time at the Phillips Collection, as part of the museum's latest Artful Evening, to draw attention to its most recently opened exhibit, Paul Klee and America. This took place in the fancy new auditorium in the museum's renovated wing, a nice place to hear a lecture but not yet without some technical kinks. After extensive pre-lecture sound checks, which held up a sizeable crowd from entering, there was still feedback during the introduction of the speaker.

| Available at Amazon: Gunther Schuller, Seven Studies on Themes of Paul Klee and other orchestral works (released on September 15, 1998) |

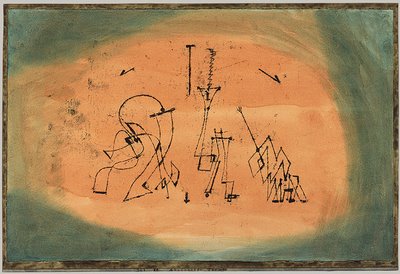

For each painting, Schuller explained, he analyzed the movement and form and assigned musical ideas that could express them. For the irregular pattern of colored blocks in Alter Klang (Antique Harmonies, 1925), he created blocks of sound, made up of the old, fundamental intervals of Western music, 4ths and 5ths. For the rows and rows of shapes representing the world of nature in Pastorale (1927), he layered up overlapping rhythmic ostinatos. For the three quirky and abstracted musicians in Abstraktes Terzett (Abstract Trio, 1923) -- the only painting featured in the piece that is actually in the Phillips exhibit (shown below) -- he selected a chamber assortment of four instrumental trios, giving them all jagged melodies, first as separate trios and then all together.

The most famous movement of the seven, The Twittering Machine (1922), was explained by Schuller as a "parody of serialism," the aviary of birds creating the sound that Klee's strange bird machine cannot produce. All the instruments create a 12-tone fabric of sound, an ingenious image for the mechanization of composition that is often criticized in the 12-tone style. Schuller was quick to point out, however, that his parody is mostly a good-hearted joke, since he has used the 12-tone style in his own work. We heard recorded examples of each movement after Prof. Schuller had introduced them. In a grand gesture that says a lot about the state of classical music audiences, he gave his listeners permission to laugh at the silly sounds of the Twittering Bird movement, the one piece that has become truly famous of the seven. And laugh we did, as Schuller's piece described the turning of the machine's crank, the ever faster whirring of the birds, the phonograph-like winding down of the machine's internal machinery, and a final, frenetic gasp after a quick second cranking.

In a short and genial question period after this lecture, Gunther Schuller showed more of the professorial persona that is so charming. In answer to one query, he replied, "I am the eternal student": even at 81, he is still seeking, still learning, still able to appreciate new perspectives. Long may he do so.

In a short and genial question period after this lecture, Gunther Schuller showed more of the professorial persona that is so charming. In answer to one query, he replied, "I am the eternal student": even at 81, he is still seeking, still learning, still able to appreciate new perspectives. Long may he do so.I took a brief turn through the exhibit, too, which is not a major retrospective but is focused around Klee's relationship with the United States. There are some major works, but the absence of nearly all the paintings selected for musical setting by Schuller gives an idea of what has been brought together -- and what has not. (One other painting at the Phillips, Neue Harmonie from 1936, now at the Guggenheim, is clearly related to Alter Klang, mentioned above.) It is a good opportunity to get a fuller idea of Klee's work, with many paintings owned by Germans and other Europeans who emigrated to the United States at around the same time that Klee himself was ruined by the Nazis and driven into exile. Much of the wall text is concerned with the idea of the United States in Klee's painting and who his major patrons in America were.

Some of the works selected are very rudimentary sketches, the value of which in this sort of exhibit seems low to me. These sorts of works, if they are not extraordinary in and of themselves, are most interesting if they are hung next to the more finished versions that followed them. As a tribute to Klee's fascination with the artwork of children, there is an accompanying exhibit of charming children's drawings, along with an extensive exhibit of the artwork of D.C. public schoolchildren on the lower level of the new annex.

There were a few other paintings with musical themes that stuck out as I perused the exhibit, beginning with the watercolor Notturno für Horn (1921), now in a private collection, which I am surprised that Schuller, an accomplished horn player, did not take up for his piece, if he knew about it. A quintessentially musical character of mythology appears in another watercolor, Orpheus (1929), also from a private collection. Finally, a painting purchased by Duncan and Marjorie Phillips, the Arabisches Lied (1932, oil on burlap), shows the veiled face of a person singing, whose mouth and nose appear to have been transformed into an abstract flower.

No comments:

Post a Comment