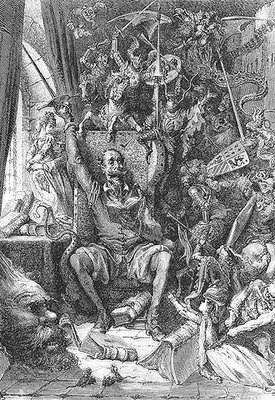

Don Quixote and Music, Part 4

| Available at Amazon: Don Quixote, new translation by Edith Grossman (released on October 21, 2003) Don Quixote (online version, English translation) Don Quijote (online version, Spanish original) Ruta de Don Quijote (pilgrimage route following Don Quixote around Spain) Don Quijote de La Mancha: Romances y Músicas, Montserrat Figueras, Hespèrion XXI, La Capella Reial de Catalunya, Jordi Savall (released on January 10, 2006) |

Part 5 | Part 6 | Part 7 | Part 8

For lack of mention of music in the text of Cervantes, Savall's recording skips over many of the most memorable passages, including Don Quixote's attack on the two herds of sheep, which he takes to be two opposing armies, and the attack on the group of penitents carrying a dead body. Richard Strauss also set these episodes to memorable effect in his tone poem based on the novel, and most people would probably think of one of them, or the attack on the windmills, if asked to identify a story from Don Quixote. What Savall's recording does is to flesh out the rest of the story. I tend to read quickly, and I admit that I move more quickly over the poetic interpolations in the novel than I probably should. Listening to the recording as much as I have, however, I have absorbed the poems much more and now have a sense of the musical content of the story behind them.

The next section of the recording (Lying at their ease in the shade) brings us the music for the next song, found in Chapter 27. Don Quixote's concerned friends have come to find him at the place where he isolated himself in the wilderness, in the Sierra Morena. It is mid-August, and the heat is heavy. They sit down in the shade of a copse of trees by a gently flowing brook:

And then, as they were taking their ease in the shade, they caught the sound of a voice, which, unaccompanied by an instrument of any kind, reached their ears with a sweet and regular cadence. They were quite astonished at hearing so good a singer in a place like this; for though it is said that in the wood and fields one comes upon shepherds with superlative voices, this is an embellishment of the poets rather than the truth, and they wondered still more when they discovered that these were not such verses as rustic herdsmen compose but were, rather, the work of a city-bred poet. [...] The hour, the season, the solitude, the voice and skill of the singer aroused admiration in the listeners and brought them contentment as they waited to see if there was more of the song.In effect, the two men, who are refined enough to recognize good poetry and music, hear two songs: a pastoral poem ("Who robs me of my ease and gives me pain?), presented here in a setting by Sant Juan, and a sonnet ("Sacred friendship, who on wings of air"), to music by Francisco Peñalosa. Both are pieces of Spanish music of the period, adapted to the words penned by Cervantes. Even though these are speculative reconstructions, the words are meant to enter the mind through the vehicle of melody. Here Lluís Vilamajó sings both songs unaccompanied, with a pure and sweet tenor that is a nice contrast with the Song for Olalla, the goatherd's song mentioned in my last post.

Much of the remainder of the first part of Don Quixote is not really about the title character. In fact, a series of new characters join the narrative at the same inn, telling their own stories, in the sort of frame narrative technique accomplished so skillfully by Boccaccio, Chaucer, and others. The first of these is the Sierra Morena story, a modern romance of a young couple not allowed to marry. Here is where Cervantes further skewers the fantasy epic that has driven Don Quixote to insanity. Don Quixote plans to "pretend to be crazy" deliberately in the wilderness, in imitation of the heroes in his books (especially Amadis de Gaula and Orlando Furioso) as a way to show Dulcinea his faithful devotion. Cervantes contrasts this eccentric and frankly idiotic activity with the young protagonist of the story, Cardenio, who actually does go crazy in the wilderness because of the series of bad events that he recounts. Fortunately, Don Quixote's friends, the concerned barber and curate, are able to bring both their friend and Cardenio out of the Sierra Morena.

Much of the remainder of the first part of Don Quixote is not really about the title character. In fact, a series of new characters join the narrative at the same inn, telling their own stories, in the sort of frame narrative technique accomplished so skillfully by Boccaccio, Chaucer, and others. The first of these is the Sierra Morena story, a modern romance of a young couple not allowed to marry. Here is where Cervantes further skewers the fantasy epic that has driven Don Quixote to insanity. Don Quixote plans to "pretend to be crazy" deliberately in the wilderness, in imitation of the heroes in his books (especially Amadis de Gaula and Orlando Furioso) as a way to show Dulcinea his faithful devotion. Cervantes contrasts this eccentric and frankly idiotic activity with the young protagonist of the story, Cardenio, who actually does go crazy in the wilderness because of the series of bad events that he recounts. Fortunately, Don Quixote's friends, the concerned barber and curate, are able to bring both their friend and Cardenio out of the Sierra Morena.The final section of the first part of the CD (A voice that chants enchantingly) takes us over many chapters to Chapter 43. In a sense, it is only Don Quixote's misguided wandering that has brought all of these characters together in the simple country inn, where they eventually meet those whom they have lost. As Cervantes ties all of these external stories together, the now large band of characters tries to sleep in the cramped conditions, with all of the women together in one large room:

And so it was that, shortly before daylight, the womenfolk heard a voice so sweet and musical that they were compelled to pay heed to it, especially Dorotea, who was lying there awake while Doña Clara de Viedma, the judge's daughter, slumbered by her side. None of them could imagine who the person was who sang so well without the accompaniment of any instrument. At times the singing appeared to come from the courtyard, at other times from the stable. [...] It occurred to Dorotea that it would not be right to let Clara sleep through it all and miss hearing so fine a voice, and so, shaking her from side to side, she roused her from her slumbers. "Forgive me for waking you, my child," she said. "I do it because I wish you to hear the best singing that you have ever heard in all your life, it may be."We learn that the singer is none other than the man who loves Clara, from whom she has been separated. That praise-filled description is a hard one for most singers to try to match, but Savall has his own son, Ferran Savall, sing a Sephardic melody adapted to the lovely poem by Cervantes. The young Savall has a light and very high tenor, straight and almost pop music-like in its affectation. The effect is quite lovely and appropriate. Savall recently performed in Paris with his wife and two children. There was an interview («La musique ancienne parle à l'âme», May 18) with Bertrand Dermoncourt in L'Express and reviews in Le Monde and Libération, neither available online except for a fee.

Music and poetry are central to Don Quixote's story, because as he tells Sancho, "all or nearly all knights-errant in ages past were great troubadours and musicians, both these accomplishments -- or better, graces -- being characteristic of love-lorn and wandering men of arms" (Chapter 23). What the musical interpolations seem to be telling us are that those old songs are still around, sung by men (no women, yet) from all walks of life, not just the noble troubadours or their modern, crazy equivalent. In fact, Cervantes intentionally renders Don Quixote's attempts at poetry ridiculous. (He never sings, which is probably for the best.) The best example is the only poem that survives of the inscriptions Don Quixote leaves in the wilderness, in which he destroys the scansion of the final line of each stanza, by adding "del Toboso" as an afterthought each time he wrote "Dulcinea" (Chapter 26).

Like Voltaire's Candide, Don Quixote is an optimist, always searching for the rosy way to interpret life's misfortunes, often to the chagrin of Sancho Panza. At one point, he tells his squire, "All these squalls that we have met are merely a sign that the weather is going to clear and everything will turn out for the best" (Chapter 18). Also reminiscent of Voltaire's equally semiautobiographical story, Don Quixote and Sancho's trials are often just as funny as they are painful. In one of the grossest passages in the book, knight and squire ingest a disgusting homemade elixir supposed to have magical curative properties, which causes them to vomit on one another (Chapter 18). This is a real "South Park" moment.

(To be continued.)

No comments:

Post a Comment