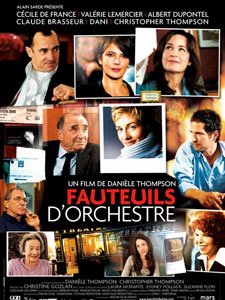

Fauteuils d'Orchestre

A dear friend in Paris advised me to see the new film by Danièle Thompson, Fauteuils d'Orchestre (Orchestra Seats). Although I was not able to do that during my trip to Paris, I did manage to make it to the inaugural reinstitution of the Cinémathèque (formerly the Cine-Club) at La Maison Française, a special screening of this charming, sugary movie. Danièle Thompson got her start writing screenplays, most famously a partial credit for a marvelous history film, La Reine Margot. In the last several years, she has been directing her own comic screenplays, beginning with La Bûche (1999) and Décalage horaire (2002). For Fauteuils d'orchestre, she worked with her son, Christopher Thompson, on the screenplay, and he plays the lead romantic role in the movie as well.

A dear friend in Paris advised me to see the new film by Danièle Thompson, Fauteuils d'Orchestre (Orchestra Seats). Although I was not able to do that during my trip to Paris, I did manage to make it to the inaugural reinstitution of the Cinémathèque (formerly the Cine-Club) at La Maison Française, a special screening of this charming, sugary movie. Danièle Thompson got her start writing screenplays, most famously a partial credit for a marvelous history film, La Reine Margot. In the last several years, she has been directing her own comic screenplays, beginning with La Bûche (1999) and Décalage horaire (2002). For Fauteuils d'orchestre, she worked with her son, Christopher Thompson, on the screenplay, and he plays the lead romantic role in the movie as well.

The various plot strands are brought together around a young drifter from the provinces, Jessica (the impossibly cute Cécile de France). Following the lead of her beloved grandmother (Suzanne Flon, who died in post-production and to whom the film is dedicated), she moves to Paris and lies and scraps her way into a job at the café across the street from the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées (where I recently heard Sandrine Piau, which made the movie personal in a fun way). Slowly, the irresistible Jessica crosses paths with a concert pianist, Jean-François Lefort (Albert Dupontel), playing the Emperor concerto at the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées; Claudie (Dani), the whiskey-voiced gardienne of the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées; Catherine Versen (Valérie Lemercier), an actress starring in a Feydeau play at the Comédie des Champs-Élysées next door; and a wealthy art collector, Jacques Grumberg (Claude Brasseur), putting up his art for auction at the Hotel des Ventes Drouot-Montaigne, also next door. It's an ingenious way to embed a story in a quartier particulier, even though one character remarks in the film about this neighborhood, quite correctly, "c'est pas un quartier." That area of Paris is a collection of buildings, some of which have people in them, but the combination of luxury hotels and a lack of places to eat and buy normal things like groceries makes it inhospitable. Of course, it is now impossible to make a whimsical movie set in Paris without setting oneself up for comparison with Jean-Pierre Jeunet's Le fabuleux destin d'Amélie Poulain (2001). As I have written before, this is unfair, since Jacques Demy was making whimsical movies, just not really about Paris, long before Amélie. Jeunet's film was goofy in a way that Fauteuils is not, although it is definitely a long way from that depressing realism we associate with French cinema. Some parts of the various plots are over the top and do not ring true, but the fantasy is just fine with me. It's a droll story, smart in its intellectual leanings. The biggest laugh for me was related to American director Brian Sobinski (played by Sidney Pollack, in a funny mixture of French and English), who is casting a new biopic on Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir. At one point, with no textual reference to give away the joke, there is a cutaway to a waiting room with five actors lined up against the wall in chairs, all ringers for Jean-Paul Sartre, with pipes and glasses.

Of course, it is now impossible to make a whimsical movie set in Paris without setting oneself up for comparison with Jean-Pierre Jeunet's Le fabuleux destin d'Amélie Poulain (2001). As I have written before, this is unfair, since Jacques Demy was making whimsical movies, just not really about Paris, long before Amélie. Jeunet's film was goofy in a way that Fauteuils is not, although it is definitely a long way from that depressing realism we associate with French cinema. Some parts of the various plots are over the top and do not ring true, but the fantasy is just fine with me. It's a droll story, smart in its intellectual leanings. The biggest laugh for me was related to American director Brian Sobinski (played by Sidney Pollack, in a funny mixture of French and English), who is casting a new biopic on Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir. At one point, with no textual reference to give away the joke, there is a cutaway to a waiting room with five actors lined up against the wall in chairs, all ringers for Jean-Paul Sartre, with pipes and glasses.

The problem encountered by the concert pianist is that he has come to despise the classical music culture. He is upset that Jessica feels intimidated by classical music, which she does not really know or understand. He enjoys playing Liszt (Consolation No. 3) for a group of patients at a hospital but ends up stripping off his tuxedo -- one of those unrealistic scenes -- when playing a concert at the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées. Music bloggers have been chewing on the related question of how to bring broader audiences back -- or, rather, for the first time -- to listening to classical music. Will young people come to concerts if there are martini bars? Singles' nights? A dance club ethos? Cheaper tickets? Is the atmosphere of classical concerts terminally stuffy? Would it help if classical composers start using more popular idioms? If they use pop music voices -- amplified, of course -- would that help? Is there not enough classical music education in schools? No one can tell. In an interview with Fernand Denis (Danièle Thompson: les artistes sont insatisfaits, March 8) for La Libre Belgique, Danièle Thompson had the following to say about the inspiration for the character played by Albert Dupontel:

Cinema is much less restrictive than classical music. This character was inspired by a pianist, François-René Duchâble, a friend who exploded about three years ago. He also did something crazy: he attached his piano to a helicopter and dumped it into Lake Annecy. The musical world felt like he was spitting in their faces. I, too, wanted to express that transgression against a taboo, that revolt against the straitjacket. But any artist can go to pieces like that. I still remember when Daniel Day Lewis messed up in Hamlet and left a prestigious London theater in the middle of the show. It was the beginning of a serious depression.I agree with the newspaper critics that Valérie Lemercier's performance is the best. She makes a ridiculous salary acting in a glorified television soap opera and rankles that people everywhere recognize her and love her for it. In her bid to land the role of Simone de Beauvoir, she pulls out all the stops, including ranting to the American director about de Beauvoir's real identity, about which the French intellectual world has recently adjusted its perception (see my post on de Beauvoir two years ago). Best of all, seeing that the American director is in the audience to watch her Feydeau play (Mais n'te promène donc pas toute nue, 1912), she shamelessly improvises, throwing off the famously outrageous hat to reveal her hair done exactly as de Beauvoir wore it. Throughout, the comedy is never heavy-handed, making this an overall enjoyable film.

Jean-Luc Douin, "Fauteuils d'orchestre" : chassés-croisés et bons sentiments (Le Monde, February 15): With talent (Danièle Thompson has it) and good actors (see the cast list), it certainly manages to make us laugh, to move us, which is the goal. That is not enough, however, to remove the superficial nature of these intersecting plots or to dispel the thin layer of feel-goodness. [...] But there is Valérie Lemercier, who plays a bitch on wheels tired of acting in Feydeau and television series, a viper-tongued flatterer, who twice tries to seduce an American director in Paris to finish casting his movie. In particular, the scene where she dines alone with him and explains in a clownish franglais how she would interpret Simone de Beauvoir is a great moment. She dares to make a big deal of it, squealing, a face of tics, false modesty, seduction, wielding an irresistible inventory of grimaces. She is worth the ticket by herself. | Marie-Noëlle Tranchant, Paris est une fête (Le Figaro, February 15): Danièle Thompson has created (with her son Christopher, co-screenwriter) an ideal comedy: sparkling with intelligence and elegance, precise and light, joyous and sensitive, touching on bitterness and the pains of life while leading them into a healing generosity. The most beautiful scene in the film has a poignant gravity, a mysterious dialogue between music and suffering, and it is remarkable to see how perfectly it fits into the middle of a comedy, isolated like a pure tear, and nevertheless secretly prepared by the melancholy characters. Their heart has its secret, and their soul its mystery. Dupontel creates a virtuoso inspired by François-René Duchâble (the film's music consultant), tired of the show; Brasseur, a man who sees his own end approaching; alone in this trio of beautiful people, Valérie Lemercier is a comic character, a media celebrity with intellectual pretensions whom she makes irresistible. | Fernand Denis, L'auteur est au balcon (La Libre Belgique, March 8): If the tone chosen by Danièle Thompson is decidedly light, there is a whiff of retrospection after 40 years writing screenplays and three feature films. Fauteuils d'orchestre is a rather skillful film because it uses, paradoxically, the spunky Cécile de France to confront the problem of old age and some of its questions. The transfer, for example, through the enthusiasm that the marvelous grandmother Suzanne Flon inspires in her granddaughter. The inheritance? What does one leave to one's children, asks this man who has understood everything about business, about art, but nothing about his children. |

No comments:

Post a Comment