Political Piano: Zimerman at Shriver Hall

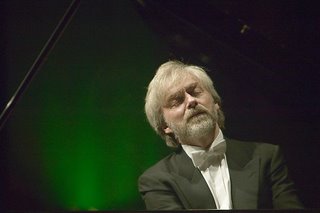

Krystian Zimerman has made a name for himself as one of the great pianists of our time – one of the few I would include in that rarified first tier of pianists where no more than half a dozen pianists roam. Relative scarcity may well play a part in this. Whenever he makes a recording or appearance, it becomes an ‘event’. Particularly meticulous with recordings, few of his ever receive anything less than highest praise. (He's just released a recording of the Brahms d-minor concerto that created some stir, for example.)

Krystian Zimerman has made a name for himself as one of the great pianists of our time – one of the few I would include in that rarified first tier of pianists where no more than half a dozen pianists roam. Relative scarcity may well play a part in this. Whenever he makes a recording or appearance, it becomes an ‘event’. Particularly meticulous with recordings, few of his ever receive anything less than highest praise. (He's just released a recording of the Brahms d-minor concerto that created some stir, for example.)

Grażina Bacewicz, Piano Quintets, Piano Sonata No.2 K.Zimerman, K.Danczowska, A.Szymczewska, R.Groblewski, R.Kviatkowski DG |

Then came Beethoven’s Pathétique, op. 13. And with it a dramatic – indeed pathetic – dedication to those men in prison who have had no fair trial because “some men broke the law because they decided to be the law.” Despite some supportive hollers, the air of inappropriateness hung heavy over Shriver Hall at that unexpected political outburst. I am sure that the assorted inmates at Gitmo – terrorists, soldiers, innocents, and Mudjaheddin alike – (the kind who support regimes that outlaw Beethoven, blow up statues of Buddha, condemn converts to Christianity to death, generally unenthusiastic about womens' rights) appreciated his gift of the Beethoven sonata tremendously. At least as much as the present Polish Ambassador must have appreciated Zimerman’s venture into his business. (At any rate, if he had been serious about his statement, he should have played the Fidelio transcription.)

Were the violent outbreaks in the Grave: Allegro di molto e con brio political statements, too? Was letting the chord just before the Adagio (measure 294) ring forever and then some? Or taking the first repeat back to the beginning, not just the Allegro? Nice touches in that first movement, but it was all over the place. The Adagio Cantabile was better; strong while melancholic, moving but never wavering, dramatic in a very specific sense: self-consciously hurtling itself to the end – a tragic one or one of resolve we don’t know until the final notes. The Rondo started bubbly, only to offer harsh cliffs. With eccentricities sprinkled everywhere and some anger management in the banged-out chords of the Allegro part of the third movement, the Beethoven was a very mixed bag.

The second half started with much-anticipated Chopin – the F minor Ballade, op. 52. Tempi were pulled here and there, not in a grid of rubato (Pollini-style), nor swimming slowly, loosely (Arrau). But then, especially in passages that eschew extremes of tempi or volume there were profoundly beautiful, exquisitely judged moments. The three hushed chords leading into the coda might be a question of personal taste as he played them, as was the Debussy-like opening of separate color dots that were supposed to come together as a coherent introduction. The run-up to the finale was undoubtedly the most impressive part of this Ballade: like clockwork did those fingers accentuate every individual note in that very dense and fast passage work.

I’ve always listened to Ravel’s Valses Nobles and Sentimentales more than my appreciation of them actually would merit – both in piano and orchestral versions – because the music, in its orchestrated form made for a ballet named Adélaïde (…ou le langage des fleurs). Long story I won’t get into. If I am to enjoy these thoroughly, they had better be played to the hilt. And here Krystian Zimerman’s attitude-filled playing worked splendidly for me! Violent and contemplative stresses and emphases, zooming in on one element, brushing over another, he turned those waltzes into wholly unpredictable little things. At the anonymous premiere the audience could not guess Ravel its author. Some - at that premiere - apparently thought ‘Satie’. Ridiculed as that suggestion is nowadays, Zimerman could have sold me those waltzes as Satie for a premium. Loved it. (His Ravel excellence is not surprising: his recording of the two piano concertos absolutely towers over any and all competition – a must-have for anyone remotely interested in Ravel, Zimerman, or piano concertos.)

Concluding the recital – before he was off, encore-less, despite wildest ovations – was the Grazyna Bacewicz Sonata no. 2. Music that has its home in a black pool of deep sounds all the way on the left of the keyboard, it jumps to life, repeatedly, into the higher register. Every one of its three movements ends contemplatively. It was delivered with panache and his usual, incredible skill – and a weird, personal story (the sonata is about “war, suffering, freeing people” – again) after which I had the impression that his daughter had been liberated by English officers from a German concentration camp. (Zimerman – the ninth Chopin International Piano Competition winner – was born on December 5th, 1956.) Whatever he meant, it is a work obviously close to his heart, and he won many new ears for it with his performance.

Follow @ClassicalCritic

|

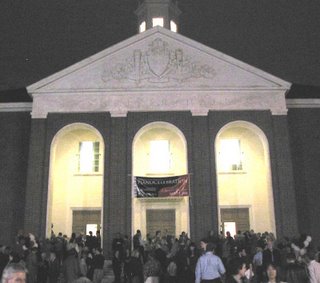

In 1965, Dr. Ernst Bueding and a group of Johns Hopkins faculty started the concert series at Shriver Hall. On Friday night, Ionarts was on hand to help celebrates its 40th anniversary, with the opening of a three-day Piano Celebration of concerts, lectures, and other presentations. A banner and bunches of balloons decorated the entrance, and all audience-members were invited to lift a cup of complimentary wine. The fact that we have made a number of trips up to Baltimore over the short history of Ionarts should indicate the high quality of the concerts they offer, over 200 since that first season 40 years ago.

The chance to hear Krystian Zimerman was certainly enough to draw me to Baltimore for this concert. I have long admired his recording of the Chopin ballades but had never had the chance to hear him live. What struck me most was the pianistic range of touch, even on an instrument of which he disapproved. The Mozart K. 330 was both gentlemanly and giocoso, light of hand, with carefully distinguished differences between détaché and legato. Even from our not bad (yet somewhat far left) vantage point, his hand seemed never to strike the key without forethought. On the other hand, there were almost Chico Marx-like moments of play, as Zimerman lifted his right leg up under the piano at moments of abandon and humorously skipped his finger across the keys in the main theme of the Allegretto. I found the same sense of humor in the Ravel waltzes, especially in the more introspective passages -- alternately torpid and saccharine or elfin and feathery -- between the stormy crashing passages, one of which induced the audience to applaud in the middle of the work.

As expected, the Chopin fourth ballade was everything I could have hoped. I am not sure that being Polish would actually help Zimerman understand Chopin's music more than other players, but it certainly seems that he is more in the composer's skin than many others. Robert Schumann wrote that Chopin had told him that the ballades were based on poems by Poland's national poet, Adam Mickiewicz, apparently words that the composer cherished in his self-imposed exile from his homeland. (The calm homophonic tune in the second ballade may be a setting of an unspecified Mickiewicz poem in trochaic meter.) This has been discussed in much greater detail by musicologists, of course (for example, see Dorota Zakrzewska, Alienation and Powerlessness: Adam Mickiewicz's Ballady and Chopin's Ballades, an article in the 1999 volume of Polish Music Journal). The ballades have a strong Polish connection, and Zimerman's playing had an enigmatic, at times almost ghostly, character. More to come from Baltimore this weekend.