Notes from the 2013 Salzburg Festival ( 5 )

Jeanne D'Arc • Walter Braunfels

Walter Braunfels • Jeanne D'Arc

The Would-Be Future of Opera at Stake

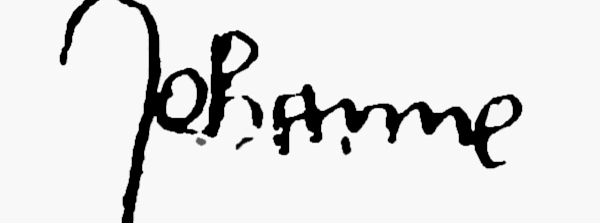

Jeanne d'Arc, signature

There is a special pleasure when an anticipated highlight turns into an experienced highlight. Walter Braunfels’ opera Jeanne D’Arc, Scenes from the Life of Saint Joan, one of the initial reasons not to miss this year’s Salzburg Festival (the other having been the hindsight-makes-you-smarter Gawain) was just such a pleasure. And indeed “pleasure” is the best-fitting description for the experience.

Happily a full Felsenreitschule greeted Jeanne D’Arc with the ORF Radio Symphony Orchestra under Manfred Honeck. Honeck is one of the few and necessary Braunfels-champions ever since he discovered this opera for a performance with the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra in Munich. He also went on to perform it with the Swedish Radio Symphony Orchestra in Stockholm which yielded a splendid recording that Decca eventually, grudgingly, generously released.

From this recording we know just how beautiful an opera Jeanne D’Arc is. There were doubts if the ORF RSO—not an orchestra that specializes in the lush and melodious, whereas opera and conductor do—would pull it off. While the performance was noticeably different from the recording, no such qualms turned out necessary. The orchestra, the Salzburg Bach Chorus, and especially the singers put on a show that made for a wholly, soundly gratifying night out at the theater. Even possible, perfectly understandable carping about the lack of a staged performance (why not Braunfels staged and Birtwistle in concert?!) were nixed by the sensitive, charming way the singers acted with their voices and their looks and facial expressions alone.

Jeanne d'Arc, Clément de Fauquembergue, 1429. Detail.

They were much helped in their compelling, enchanting ways by a libretto so uncommonly good that it merits mention ahead of any other individual ingredient. How Braufels has managed to put together from the original French and Latin 15th century trial documents of Joan of Arc a libretto that makes this distant, far-removed story and its characters not just palpable but riveting for a 21st century audience is amazing. The text is alive, sensitive to modern sensibilities, gives life to its characters, is realistic and natural, taken straight out of life, written off the mouths of actual people, and not at all stereotypically “opera”. There was genuine laughter, there were genuinely heartbreaking moments, and the ears were glued to the text—either the always clearly understandable lyrics or the supertitles—at all times, to make sure they wouldn’t miss how the story progressed. It was possible to identify with every character, whether the worries were about the 14 black-spotted piglets having died or how to best entrap Joan into making a confession and retraction.

The most touching element of them was probably the insinuated would-be love story between Joan and Gilles de Rais (a.k.a. Bluebeard). I can’t have been the only one who loved how those two—Juliane Banse and Johan Reuter (Wotan in Munich’s Ring)—played their rôles as best of friends and, as was faintly suggested by the libretto, perhaps future partners. I might have been the only one, though, to take the imagination a little further: They might have married and made a fine, hospitable castle their home—bright with many windows and flags flapping merrily in the wind. Put together with deft and tasteful hand and guided by humility and compassion. They would have had seven children: three wide-eyed, curly-headed girls in dresses with frills and four little boys who’d break their wooden swords over each other’s heads until the first splinter-pricked finger among the lot started crying. They’d all play hide and seek in the orchards on the ground… the youngest excited and giddy and the two eldest humoring them by not immediately finding the hidden rascals in the very hollow trees that they themselves had already hidden in when they were small. Joan and Gilles would have been the most popular rulers in near and far.

Miniature portrait of Jeanne d'Arc, ca.1485. Detail.

We know of course that this is not what happened, because of the flammable end of Jeanne D’Arc and because of operas about Bluebeard (Dukas and Bartók) himself. In a way Jeanne D’Arc is the prequel to Bluebeard’s Castle—it’s a story that hints at his utter devastation at the loss and fate of Joan, and how it turned him into the devastated, warped character he becomes… and how his murderous quest for women is perhaps only a quest to find the innocence and refined love that he lost with Joan’s demise. Bluebeard even has premonitions of his inner demons taking over, should he lose Jean:

M.Honeck / Swedish RSO / Banse Stensvold et al. Decca     |

If God decreed / that you should suffer harm, / I could not bear it! / A force weighs dully on me / that has nothing to do with you: / it rebels against your gentle certainty. / And if you were to fall, Joan, if you were to fall, / then I would fall, too, a long and terrible fall. / Then from the dull, black-veiled depths of my soul / a voice would struggle to break free, / the voice that groans within me: / I will not serve, / I will not, God, I will not come to you through so much suffering!

So much for fantasizing and what-ifs. Very real, however, is the music, and this music is unique, for all the helpful (or helpless) comparisons to his more-or-less contemporary opera colleagues: Richard Strauss (easily dismissed for their very different musical accent), or Paul Hindemith (who hasn’t Braunfels’ touch for melody and easygoing charm), or Hans Pfitzner (whose talent in referencing earlier musical styles rings a bell in Braunfels’ work, too), or Wagner (who pops up several times in the treatment of the voices). But the music is all inimitably Braunfels and it offers an aural window into a music—the romantic strand of it—that might have been, had it not been for the aesthetic paradigm shift after World War II. The sea of Braunfels’ music envelops the ears in its unique, yes-late-romantic but-not-the-way-we-think-of-stereotypically-late-romantic-music kind of way. Honeck tried—and succeeded to considerable degree—in making the ORF RSO play not just with precision but color and passion.

Jeanne d'Arc, illustration from a 1505 manuscript. Detail.

A passionately performing cast, virtually without weaknesses but choc-full of delights furthered the experience. The small rôle of St. Catherine was helped to unexpected prominence by the wonderfully appealing, charismatic voice of soprano Siobhan Stagg, a fresh and healthy instrument, with friendly ease through every register. St. Margaret—Sofiya Almazova—wasn’t half shabby either, with her disembodied, mysterious mezzo. Juliane Banse has made the part of Joan hers over the last decade, with a voice for the ears to embrace despite or probably because of a flattened quality with soft metallic notes. Her tasteful light silver silky shimmering dress served as a subtle homage—intended or not—to the armor of Joan, and the infusions of red an omen of things to come.

Joan’s father, Jacobus d’Arc, was sung by Tobias Kehrer with his low and perfectly enunciated voice, so clear it sounded like words etched on paper. Although a good number of notes were frayed, the comfort and clarity from top to bottom was a joy. Colin, the Sheppard, was sung by the fresh-voiced tenor Norbert Ernst, who reminded of Wagner’s David in Die Meistersinger… not surprisingly a rôle he’s sung regularly throughout his career, including at the Vienna State Opera. St. Michael was one of the exceptions, cast as he was by a singer who sounded like a failed French Heldentenor, ever-forced and nasal from somewhere down his throat.

"Jeanne d'Arc in armor before Orléans", Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres, 1854. Detail.

Robert de Baudricourt, Joan’s guardian of sorts, gets to sing in a wonderful parlando, composed right around the words, which Martin Gantner executed to composed, levelheaded perfection. Similarly Michael Laurenz as Bertrand de Poulengy (he also sang the nasty-eager Bishop Cauchon)… a singer I am surprised to learn has not yet sung the parts of Loge or even Mime. Lison, Lady Baudricourt, was Wiebke Lehmkuhl with a strong and fiercely channeled voice equally beautiful and suited to scare little children with. The Danish baritone Johan Reuter’s Bluebeard was commanding, stentorian at first, and softened with the story adding lots of sensitivity to his tone. Georges de la Trémoille, sung by the young Ruben Drole, started out with effort, but by the time he sang his extensive intermezzo before the second act he had quite come into his own… except for the ungrateful, perhaps intentionally uncomfortable high note that Braunfels squeezes in… a fact around which Drole successfully sang by giving it a mildly comic note.

Finally there was Pavol Breslik as the Dauphin and Charles VII to-be. He has a personable and dramatic voice, with natural pressure beyond it so that it can often sound anguished even when it’s not clear that that’s the intent. There’s a boyish and yet mature quality in it, which was quite apt for the haunted Dauphin. He’s also got such a distinct color that once you know his voice, you can’t miss it. His voice doesn’t adapt to characters, characters have to adapt to his voice—a quality that reminds me of his somewhat more famous tenor-colleague, Plácido Domingo. Certainly in marvelous Braunfels, that was hardly a detriment.

"Jeanne at the coronation of Charles VII", Jules-Eugène Lenepveu, 1886. Detail.

See also: