Last month | Next monthClassical Month in Washington is a monthly feature that appears on the first of the month. If there are concerts you would like to see included on our schedule, send your suggestions by e-mail (ionarts at gmail dot com). Happy listening!Saturday, April 1, 5 and 8 pm; Sunday, April 2, 2 pm

Folger Consort: Landini and MachautFolger Shakespeare Library

Saturday, April 1, 7 pm; Tuesday, April 4, 7:30 pm; Thursday, April 6, 7:30 pm; Sunday, April 9, 2 pm

Donizetti, L'elisir d'amoreWashington National Opera

Kennedy Center Opera House

See the

review by Jens F. Laurson (Ionarts, April 3)

Saturday, April 1, 8 pm

Merce Cunningham Dance CompanyKennedy Center Eisenhower Theater

See the

review by Sarah Kaufman (

Washington Post, April 3)

Saturday, April 1, 8 pm

Yundi Li, pianoMusic by Mozart, Schumann, Chopin, and Liszt

Music Center at Strathmore

See the

review by George A. Pieler (Ionarts, April 3)

Sunday, April 2, 2 pm; Wednesday, April 5, 7:30 pm; Saturday, April 8, 7 pm; Monday, April 10, 7 pm; Friday, April 14, 7:30 pm

Wagner, Das RheingoldWashington National Opera

Kennedy Center Opera House

See the

review by Jens F. Laurson (Ionarts, March 26)

Sunday, April 2, 5 pm

Natasha Mah, piano

Phillips CollectionSunday, April 2, 6 pm

Rossini,

TancrediWashington Concert OperaLisner AuditoriumSee the

review by Jens F. Laurson (Ionarts, April 6)

Sunday, April 2, 6:30 pm

Kronos Quartet, with Wu Man, pipa player

Music by Rahul Dev Burman, Michael Gordon, Terry Riley, and John Zorn

National Gallery of Art (East Building Auditorium)

Sunday, April 2, 7:30 pm

Sequenza (piano trio)

Kennedy Center Terrace Theater (Fortas Chamber Music series)

Monday, April 3, 7:30 pm

All Copland (part of

President's Festival of the Arts 2006)

CUA Symphony Orchestra

Church of the Epiphany (13th and G Streets NW)

See the

review by Daniel Ginsberg (

Washington Post, April 5)

Tuesday, April 4, 12:10 pm

Noontime Cantata:

Tue Rechnung! Donnerwort, BWV 168

Washington Bach Consort

Church of the Epiphany (13th and G Streets NW)

Tuesday, April 4, 7:30 pm

Chamber Music: All Copland (part of

President's Festival of the Arts 2006)

Ivo Kaltchev, Rome Trio, Sharon Christman

Pryzbyla Center, Catholic University

Tuesday, April 4, 8 pm

Yo-Yo Ma, cello (WPAS)

Solo cello suites by J. S. Bach

Kennedy Center Concert Hall

See the

review by Jens F. Laurson (Ionarts, April 7)

Wednesday, April 5, 7:30 pm

New Old American Songs (part of

President's Festival of the Arts 2006)

CUA Chorus

Pryzbyla Center, Catholic University

Wednesday, April 5, 8 pm

Academy of Ancient Music (Giuliano Carmignola, director)

All-Mozart program

Clarice Smith Performing Arts Center (College Park, Md.)

Thursday, April 6, 7:30 pm

Irwin Shaw's

Quiet City (part of

President's Festival of the Arts 2006)

Semi-staged reading with music by Aaron Copland (CUA Chamber Ensemble)

Pryzbyla Center, Catholic University

Thursday, April 6, 8 pm

Turtle Island String Quartet [FREE, and no ticket required]

Library of CongressThursday, April 6, 8 pm

Baltimore Symphony Orchestra: Monet and the Impressionists, with conductor Jahja Ling

Music by Debussy, Ravel, and Beethoven (Third Symphony)

Music Center at Strathmore

See the

review by Tim Smith (

Baltimore Sun, April 8)

Friday, April 7, 7:30 pm; Saturday, April 8, 7:30 pm

Aaron Copland,

The Tender Land (chamber version) (part of

President's Festival of the Arts 2006)

Pryzbyla Center, Catholic University

See the

review by Cecelia Porter (

Washington Post, April 10)

Friday, April 7, 8 pm

Juilliard String Quartet [FREE]

Music by Schubert, Viñao, and Beethoven

Library of CongressFriday, April 7, 8 pm

Krystian Zimerman, pianoShriver Hall (Baltimore, Md.)

See the

review by Jens F. Laurson and Charles T. Downey (Ionarts, April 8)

Friday, April 7, 8 pm; Saturday, April 8, 8 pm

Reto Reichenbach, pianoMusic by Martin, Brahms, Franck

Embassy of Switzerland (2900 Cathedral Avenue NW)

See the

review by George A. Pieler (Ionarts, April 8)

Friday, April 7, 8 pm; Sunday, April 9, 2 pm

Bellini, NormaVirginia Opera

George Mason University Center for the ArtsSee the

review by Grace Jean (

Washington Post, April 10) and the

review by T. L. Ponick (

Washington Times, April 11)

Saturday, April 8, 2 pm

Malcolm Bilson, lecture/piano recitalPerforming on a replica of the 1814 Nanette Streicher piano

Baltimore Museum of Art

See the

review by Jens F. Laurson (Ionarts, April 9)

Saturday, April 8, 8 pm

Leon Fleisher, pianoMusic by Bach (Capriccio in B-flat major, BWV 992, and Chromatic Fantasy and Fugue), Stravinsky (Serenade for Piano in A Major), and Schubert (Sonata in B-flat, D. 960)

Shriver Hall (Baltimore, Md.)

See the

review by Jens F. Laurson (Ionarts, April 11)

Saturday, April 8, 8 pm

Lent in Leipzig (music by Keyser, Kuhnau, J. S. Bach)

Cantate Chamber SingersSt. John’s Norwood Parish (Chevy Chase, Md.)

Saturday, April 8, 8 pm

Elmar Oliveira, violin [FREE]

Library of CongressSaturday, April 8, 8 pm [free masterclass at 1 pm]

Pacifica Quartet

Music by Mendelssohn, Janáček, Tchaikovsky

Kreeger Museum Saturday, April 8, 8 pm

National Philharmonic, with Cho-Liang Lin, violinMusic by Beethoven and Mussorgsky

Music Center at Strathmore

Sunday, April 9, 3 pm

Fazil Say, pianoMusic by Bach (Prelude and Fugue in A minor, BWV 543, and Busoni's arrangement of the D minor chaconne from the second violin partita), Beethoven (Tempest sonata), and Stravinsky (Rite of Spring for piano, four hands)

Shriver Hall (Baltimore, Md.)

See the

review by Jens F. Laurson and Charles T. Downey (Ionarts, April 12)

Sunday, April 9, 3 pm

Washington Chorus: William Walton, Belshazzar's Feast, and motets and Gloria by PoulencKennedy Center Concert Hall

See the

review by Robert R. Reilly (Ionarts, April 10)

Sunday, April 9, 6:30 pm

Eusia String Quartet, with James Dick, pianist

Music by Debussy, Fauré, and Gregory Vajda

National Gallery of ArtSunday, April 9, 7:30 pm

Courtenay Budd, soprano

Jewish Community Center of Greater Washington (Rockville, Md.)

Monday, April 10, 7:30 pm

Diotima String Quartet

Hosokawa,

Silent Flowers; Berg,

Lyric Suite; Webern,

Six Bagatelles, op. 9; Ferneyhough,

Quartet No. 2; Janáček,

Quartet No. 2La Maison Française (4101 Reservoir Road NW)

Request a reservation by sending an e-mail to Culturel.WASHINGTON-AMBA@diplomatie.gouv.fr

See the

review by Charles T. Downey (Ionarts, April 12)

Thursday, April 13, 7 pm; Friday, April 14, 1:30 pm; Saturday, April 15, 8 pm

National Symphony Orchestra, St. Matthew Passion, with Helmuth RillingKennedy Center Concert Hall

See the

review by Jens F. Laurson (Ionarts, April 14)

Thursday, April 13, 8 pm

Lang Lang, piano (WPAS)

Music Center at StrathmoreSee the

review by George A. Pieler (Ionarts, April 15)

Friday, April 14, 8 pm

Choral Arts Society of WashingtonMusic Center at Strathmore

See the

review by Jens F. Laurson (Ionarts, April 17)

Saturday, April 15, 8 pm

Left Bank Concert Society: Shades of Our TimesMusic by Moravec, Dutilleux, Ewazen, Stucky, and Bartók (String Quartet No. 5)

Clarice Smith Performing Arts Center (College Park, Md.)

See the

review by Cecelia Porter (

Washington Post, April 17)

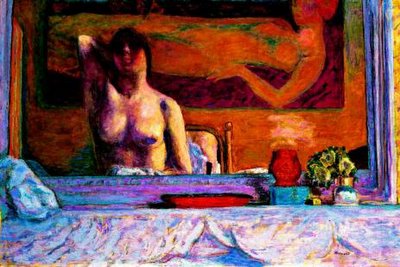

Sunday, April 16, 5 pm

Haskell Small, piano

World premiere of commissioned composition:

Renoir’s FeastPhillips CollectionSee the

review by Joan Reinthaler (

Washington Post, April 18)

Monday, April 17, 8 pm

National Symphony Orchestra/JCC Chamber Music Series

Jewish Community Center of Greater Washington (Rockville, Md.)

Thursday, April 20, 7 pm; Friday, April 21, 8 pm; Saturday, April 22, 8 pm

National Symphony Orchestra: Rafael Frühbeck de Burgos, conductor/Julian Rachlin, violinMusic by Beethoven (Sixth Symphony), Prokofiev (second violin concerto), and Stravinsky (Firebird Suite)

Kennedy Center Concert Hall

See the

review by Jens F. Laurson (Ionarts, April 21)

Thursday, April 20, 7:30 pm

Garth Newel Piano QuartetMansion at Strathmore

Thursday, April 20, 8 pm; Friday, April 21, 8 pm

Mendelssohn Piano Trio with Michael Stepniak (viola) and Claudia Chudacoff (cello)Robert Schumann Festival

Embassy of the Federal Republic of Germany (4645 Reservoir Road NW)

Thursday, April 20, 5 pm

Alex Ross (of

The New Yorker and The Rest Is Noise), “Hitler and Stalin as Music-Lovers”

Peabody Musicology Colloquium

Cohen-Davison Theatre at Peabody (Baltimore, Md.)

See the

calamity summary by Charles T. Downey (Ionarts, April 22)

Friday, April 21, 7:30 pm; Sunday, April 23, 3 pm; Tuesday, April 25, 7:30 pm; Thursday, April 27, 7:30 pm; Saturday, April 29, 7:30 pm; Sunday, April 30, 3 pm

Cimarosa, Il Matrimonio SegretoUniversity of Maryland Opera Studio, conducted by Ryan Brown

Clarice Smith Performing Arts Studio (College Park, Md.)

See the

review by Charles T. Downey (Ionarts, April 28)

Friday, April 21, 8 pm

Washington Bach Consort [FREE]

Bach's Cantata

Es ist das heil uns kommen her, BWV 9, and twentieth-century choral works by American composers

Library of CongressSee the

review by Joe Banno (

Washington Post, April 24)

Friday, April 21, 8 pm

Trio Solisti with David Krakauer, clarinetMusic by Moravec

Barns at Wolf Trap (Vienna, Va.)

See the

review by Cecelia Porter (

Washington Post, April 24)

Saturday, April 22, 4:30 pm

San Francisco Symphony Orchestra, with Michael Tilson Thomas, conductor (WPAS)

Music by Debussy,

Berg Ravel, Mahler, and Wagner

Lulu Suite, with soprano Celena ShaferReplaced by Jean-Yves Thibaudet, Ravel's Piano Concerto in D Major for Left Hand

Kennedy Center Concert Hall

See the

review by Jens F. Laurson (Ionarts, April 26)

Saturday, April 22, 8 pm

National Philharmonic, with Philip Hosford, pianoMusic by Haydn, Salieri, and Mozart

Music Center at Strathmore

See the

review by Mark J. Estren (

Washington Post, April 24)

Saturday, April 22, 8:30 pm; Sunday, April 23, 7:30 pm

Jerusalem Quartet

Jewish Community Center of Greater Washington (Rockville, Md.)

See the

review by Charles T. Downey (Ionarts, April 24)

Sunday, April 23, 3 pm

The Master Chorale of WashingtonMusic by Copland and world premiere by Hailstork

Kennedy Center Concert Hall

See the

review by Tim Page (

Washington Post, April 25)

Sunday, April 23, 4 pm

Verdi,

RequiemNew Dominion ChoraleRachel M. Schlesinger Concert Hall (Alexandria, Va.)

See the

review by Mark J. Estren (

Washington Post, April 26)

Sunday, April 23, 4:30 pm

Contemporary Music ForumMusic by Frederick Weck, Douglas Boyce, Steve Antosca, and Miroslav Pudlak

Corcoran Gallery of Art

See the

review by Daniel Ginsberg (

Washington Post, April 26)

Sunday, April 23, 5 pm

Gregory Sioles with Marcolivia, piano trio

Phillips CollectionSunday, April 23, 6:30 pm

Piotr Andrszewski, pianist

Music by Bach, Mozart, and Karol Szymanowski

National Gallery of ArtSee the

review by Jens F. Laurson (Ionarts, April 27)

Monday, April 24, 7:30 pm

Ensemble Doulce Mémoire17th-century French music, with Baroque dance

La Maison FrançaiseSee the

review by Charles T. Downey (Ionarts, April 26)

Monday, April 24, 8 pm

Itzhak Perlman, violin, and Pinchas Zukerman, violin/viola (WPAS)

Kennedy Center Concert Hall

See the

review by Jens F. Laurson (Ionarts, April 28)

Tuesday, April 25, 7:30 pm

Efe Baltacigil, cello (WPAS)

Kennedy Center Terrace Theater

See the

review by Jens F. Laurson (Ionarts, April 29)

Wednesday, April 26, 7:30 pm

Shanghai Quartet [FREE]

Bartók, first string quartet; Ravel, Quartet in F; Yi-wen Jiang, ChinaSong

Freer Gallery of ArtSee the

review by Jens F. Laurson (Ionarts, May 2)

Thursday, April 27, 7 pm; Friday, April 28, 8 pm; Saturday, April 29, 8 pm

National Symphony Orchestra: Mstislav Rostropovich, conductor/Dawn Upshaw, sopranoMusic by Bernstein (Slava! [A Political Overture]), Britten (Peter Grimes Sea Interludes), Dutilleux (Correspondances, 2003), and Dvořák (Eighth Symphony)

Kennedy Center Concert Hall

See the

review by Jens F. Laurson (Ionarts, April 28)

Thursday, April 27, 8 pm; Friday, April 28, 8 pm; Sunday, April 30, 3 pm

Baltimore Symphony Orchestra, with conductor Carlos KalmarProgram includes John Adams,

On the Transmigration of SoulsConcert Artists of Baltimore Symphonic Chorale and Peabody Children's Chorus

Meyerhoff Symphony Hall (Baltimore, Md.)

See the

review by Charles T. Downey (Ionarts, April 29)

Friday, April 28, 7 pm

Georgetown University Chamber Singers, “Sing Joyfully”

Byrd’s “Mass for Four Voices”, “Ave Verum Corpus,” and “Sing Joyfully”

Dumbarton United Methodist Church (3133 Dumbarton Street NW)

Friday, April 28, 7:30 pm

East Coast Chamber OrchestraKennedy Center Terrace Theater

See the

review by Mark J. Estren (

Washington Post, May 1)

Friday, April 28, 7:30 pm

Antoine Tamestit (viola) and Alexis Descharmes (cello)

Contemporary, mostly Hungarian music

La Maison FrançaiseFriday, April 28, 8 pm

London Haydn Quartet, with Eric Hoeprich, clarinet [FREE]

All-Mozart program: Clarinet Quartet in B-flat Major (18th-c. arr. of Violin Sonata, K. 378), String Quartet in F Major, K. 590 ("Prussian"), Fugues in C minor and D Major for string quartet, K. 405 (arr. of BWV 871 and 874), and Clarinet Quintet in A Major, K. 581

Library of CongressSee the

review by Stephen Brookes (

Washington Post, May 1)

Friday, April 28, 8 pm

Weilerstein TrioAll-Dvořák program

Corcoran Gallery of Art

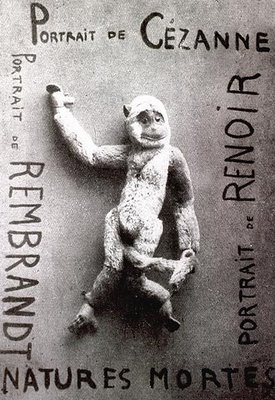

Saturday, April 29, 4:30 pm

Ute Lemper, vocalist [CANCELLED]

Cabaret concert, presented in honor of Dada

National Gallery of Art (East Building Auditorium)

Saturday, April 29, 5 pm

21st Century Consort, with soprano Lucy Shelton

Tom Flaherty, When Time Was Young; Jacob Druckman, Lamia; Jon Deak, Rapunzel

Hirshhorn Museum

Saturday, April 29, 8:15 pm; Wednesday, May 3, 7:30 pm; Friday, May 5, 8:15 pm; Sunday, May 7, 3 pm

Puccini,

La BohèmeBaltimore Opera

See the

review by Grace Jean (

Washington Post, May 1)

Sunday, April 30, 3 pm

Metropolitan ChorusMusic by Vaughan Williams, Tchaikovsky, and Luis Bacalov (

Misa Tango)

Rachel M. Schlesinger Concert Hall and Arts Center (Alexandria, Va.)

Sunday, April 30, 5 pm

Christopher Guzman, piano

Phillips CollectionSunday, April 30, 6:30 pm

Modern Musick

Music by Charles Avison, Handel, Locke, Purcell, Vivaldi, and other composers, played on period instruments

National Gallery of ArtSunday, April 30, 7:30 pm

Russian Chamber Art Society

Galina Sakhnovskaya (soprano), Timothy Mix (baritone), with Tamara Sanikidze and Mikhail Yanovitsky (piano)

Vocal music by the Mighty Five

The Lyceum (Alexandria, Va.)

See the

review by Mark J. Estren (

Washington Post, May 2)

In creating this music, Chartier and Deupree were inspired by the Seascapes series of photographs made by Hiroshi Sugimoto, in response to a desire to view natural sites as primitive man might have seen them. To make these 13 large-format photographs (and four smaller ones), he traveled to seashores around the world and photographed only water and sky at the site, with no other object or person or animal in them. In most of them, the horizon line is placed right at the center of the photograph, so that the frame is equal parts light sky and dark water. The room in which they are shown is cavernous and dark, with spotlights on the photographs, assisting in Sugimoto's ritualistic plan.

In creating this music, Chartier and Deupree were inspired by the Seascapes series of photographs made by Hiroshi Sugimoto, in response to a desire to view natural sites as primitive man might have seen them. To make these 13 large-format photographs (and four smaller ones), he traveled to seashores around the world and photographed only water and sky at the site, with no other object or person or animal in them. In most of them, the horizon line is placed right at the center of the photograph, so that the frame is equal parts light sky and dark water. The room in which they are shown is cavernous and dark, with spotlights on the photographs, assisting in Sugimoto's ritualistic plan.