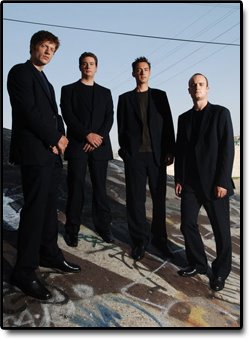

The Calder Quartet's Washington Debut: Thanks, but No Thanks!

On the surface, the Calder Quartet from Los Angeles seems the kind of West Coast ensemble where youth, flair and image are more important than substance. In general that should suffice for Washington, D.C., also. Their performance Tuesday night at the Kennedy Center’s Terrace Theater – presented as part of the Washington Performing Arts Society’s Kreeger String series – did nothing to prove either assumption wrong. The name of the quartet is a reference to the Philadelphia-born sculptor Alex “mobilé” Calder, “whose works embody the lyrical cadences and mathematical combinations of nature.” Whether the promise that lies in such flowery words was met on Thursday depends entirely on your reaction to that kind of prose.

On the surface, the Calder Quartet from Los Angeles seems the kind of West Coast ensemble where youth, flair and image are more important than substance. In general that should suffice for Washington, D.C., also. Their performance Tuesday night at the Kennedy Center’s Terrace Theater – presented as part of the Washington Performing Arts Society’s Kreeger String series – did nothing to prove either assumption wrong. The name of the quartet is a reference to the Philadelphia-born sculptor Alex “mobilé” Calder, “whose works embody the lyrical cadences and mathematical combinations of nature.” Whether the promise that lies in such flowery words was met on Thursday depends entirely on your reaction to that kind of prose.

The quartet, consisting of Benjamin Jacobson (first violin), Andrew Bulbrook (second violin), Jonathan Moerschel (viola), and Eric Byers (cello), is said to have a reputation “for choosing works from the Austro-Germanic mainstream with a bit of flair. The members of the quartet,” so states the press release, “combine the masterful and more traditional fare of Haydn’s String Quartet, op. 46, no. 1, and Beethoven’s String Quartet, op. 135, with Bartók’s Fourth Quartet.”

I see the Austro-Germanic mainstream… is Bartók the element of “flair”? Don’t get me wrong: that combination is, on paper, a near ideal evening of string quartet entertainment. But I wonder in what musical wasteland (L.A., I’d think, is clearly no such a thing) a Bartók quartet could be mistaken for something other than the most solid mainstream!? Ask a string quartet lover for the three greatest composers in that genre and you’ll get Haydn-Beethoven-Bartók as an answer most of the time. Indeed, you’d think the Bartók would be the main draw for many (including myself), as Bartók profits most from a great live performance. An enthusiastic “yes” then for having put it on the program, but a curiously raised eyebrow if that’s the quartet’s idea of adventurous programming.

The Haydn quartet that opened the whole affair was unremarkable. All four players contributed adequately for most of the time in most of the movements (the final Allegro ma non troppo coming off best, but Haydn’s joke, the false end, being a bit self-consciously employed), but the sound of the instruments was not very pleasing (the first movement’s opening was not jarring, per se, but odd) and the interpretation pedestrian.

Playing Bartók in D.C. puts any quartet up against very fine preceding performances. Most notably the Takács Quartet but also excellent offerings from the Chilingirian, Juilliard, and Zehetmair Quartets. The Bartók Fourth, one of the most energizing (perhaps even most accessible) of the half-dozen, was given a little explanation beforehand which underlined the suspicion of this being the ‘difficult’ work. There is no point in dismissing a little witty and informative introduction à la “Bartók for Dummies”; it would simply be arrogant (and furthermore wrong) to assume that everyone in an audience was already converted to Bartók’s music or that they know what “pizzicato” meant. (Gilligan, for example, only learned a few weeks ago.) What will ultimately do the job, though, is a killer performance in a great acoustic. The Terrace Theater is a wonderful venue, but it cannot compare to the Corcoran and brings no noticeable advantages for quartets over the Library of Congress’s or Freer’s stages.

The performance of the duly engaged Calder Quartet was better than in the Haydn, but the Bartók never took off, either. It lacked the bold presence in the first movement, then was sleepy instead of wide-eyed and eerily lyrical in the third movement, and didn’t muster that indelible joy and vivaciousness that makes great Bartók such an emotional spark plug. Lest anyone think the pizzicato movement (Allegretto pizzicato) is fail-safe amusement, the Calder Quartet clarified the difference between ‘amusing’ and ‘riveting’ by landing squarely on the the former. Second violinist Andrew Bulbrook alone seemed to take his plucking with the seriousness and skill that is the necessary condition for the fun to radiate from it. Despite these criticisms, the performance the four gentlemen turned in turned out to be nothing less than amiable. The last movement was – like in the Haydn – a cut above the preceding ones.

Beethoven’s late string quartets are among the most forceful, dense, and awe-inspiring works of his – perhaps even in all of music. Theirs is an inner tension that can cause unease while enlightening at the same time. The last and shortest of them, op. 135, is so no less than the others. All that, of course, presupposes a good performance – and, before a noticeably smaller audience in the second half, the Calder Quartet’s wasn’t even that. The opening notes needn’t always sound like the most somber and probing of existential questions, but I don’t like to hear them hectic and in shallow sound. Benjamin Jacobson on first violin had many pronounced difficulties (as in the Haydn Adagio) – and much of the Allegretto became an incoherent jumble of notes. The Vivace became a study in rubato – alas not with the whole quartet but among the individual instruments. Just like modern-day rubato, things started together and finished together; whatever came in between was up for grabs.

Lento assai, cantate e tranquile is the instruction above one of the most sublime Beethoven movements ever written. Its sotto voce opening could soften a stone, and it might even be said (in retrospect) to foreshadow the harmonic language of Metamorphosen, the Capriccio Sextet, Tod und Verklärung, or even Verklärte Nacht. It would have been better if the violins had played in 'piano' (and then pianissimo for the Più lento) instead of 'timid'; 'tender' instead of 'shaky'. The thrillingly confident pianissimos of a Nikolaj Znaider came to mind as contrast – or even the sometimes thin but 'steady-as-a-rock' hushed passages from the Minetti Quartett’s performance still fresh in the ears. The rest of the Beethoven wasn’t exactly butchery… but it had moments that were sad as opposed to haunting.

Lento assai, cantate e tranquile is the instruction above one of the most sublime Beethoven movements ever written. Its sotto voce opening could soften a stone, and it might even be said (in retrospect) to foreshadow the harmonic language of Metamorphosen, the Capriccio Sextet, Tod und Verklärung, or even Verklärte Nacht. It would have been better if the violins had played in 'piano' (and then pianissimo for the Più lento) instead of 'timid'; 'tender' instead of 'shaky'. The thrillingly confident pianissimos of a Nikolaj Znaider came to mind as contrast – or even the sometimes thin but 'steady-as-a-rock' hushed passages from the Minetti Quartett’s performance still fresh in the ears. The rest of the Beethoven wasn’t exactly butchery… but it had moments that were sad as opposed to haunting.

I haven’t yet heard a young professional string quartet in a professional setting that didn’t leave a more memorable impression. One always wonders after a lukewarm performance such as this if extraneous circumstances were to blame. Jet lag, illness, et al. Possibly. But merely judging from what I could hear, it stretches the imagination to think that this group was able to make “a phenomenal impact on the West Coast music scene” with an alleged “soulful intensity and effortless ability.” The quartet taught a master class at the Levine School of Music the night before their performance; one wonders whether it was in marketing or music-making. The current approach might work for four young, attractive men. But lest their playing catch up to their reputation (and quick!), their youth will go and with it their careers.