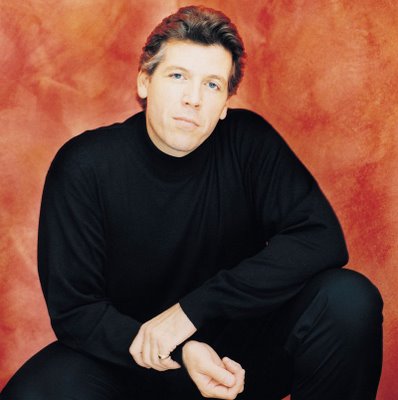

Thomas Hampson at the Library of Congress

Joe Banno, Baritone Turns The Rare Into The Well Done (Washington Post, December 9) |

In fact, this concert, cosponsored by the Vocal Arts Society, was the inauguration of a major project, involving Hampson and his Hampsong Foundation, to revive interest in America's art song. In the course of his remarks during the program, Hampson promised that there will be a Web site from the Library of Congress that will feature repertoire lists, scanned sheet music, and video and audio recordings of as many songs as possible. (This will, I presume, be added to the already remarkable collections in Performing Arts and Music from the Library's American Memory site.)

The high-profile nature of the event meant that the glitterati factor was much more in evidence than a normal concert at the Library of Congress. Not having reserved a ticket, I waited on line to take an unclaimed seat. The one I took happened to be near the front, in an uncharacteristically large reserved section, directly behind Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, who wore her coat and gloves the whole night because of the cool temperature in the auditorium. (Washington Post critic Joe Banno was seated in the row behind me. See the link to his review above.) At the intermission, I heard a waiting limo driver being told to rearrange late dinner reservations. ("Well, here are the pieces on the second half. They're all short, but the problem is that he talks, too.") This class of people does not attend too many concerts at the Library of Congress. Thank God.

Thomas Hampson did talk. There was a delightful, almost informal quality to this concert, as if your friend invited you over to hear a few songs he had found. This may explain why he lightheartedly stopped singing after two false starts, proclaiming his error and instructing his accompanist to start again, where in a different context, most performers would attempt to keep going and cover. Hampson did this with self-deprecating humor, saying "Well, that's all completely wrong" the first time and "the brain is a terrible thing to lose" the second. When, also in the second half, Hampson briefly left the stage to get a drink of water, he assured us that his absence was not because he had to look over the words of the next song.

Thomas Hampson did talk. There was a delightful, almost informal quality to this concert, as if your friend invited you over to hear a few songs he had found. This may explain why he lightheartedly stopped singing after two false starts, proclaiming his error and instructing his accompanist to start again, where in a different context, most performers would attempt to keep going and cover. Hampson did this with self-deprecating humor, saying "Well, that's all completely wrong" the first time and "the brain is a terrible thing to lose" the second. When, also in the second half, Hampson briefly left the stage to get a drink of water, he assured us that his absence was not because he had to look over the words of the next song.What he revealed in his narration of the program was an unbounded passion for this project. At one point, he admitted that he had "read through about 500 settings of Walt Whitman's poems" (three of which appeared on the program) and that one of the "great things about being a friend of the Library of Congress is that they send you things." (Thomas Hampson may think that he is the one who benefits, but I can assure you that every musicologist dreams of this sort of collaboration with performers.) Americans who agree with him, that America can learn about itself by listening to its best sung poetry: you, too, can have the experience, as we did that night, of sitting through an entire song recital without looking at the words printed in a program or translating in your mind from German, French, Italian, whatever. Thomas Hampson, after all, was singing entirely in English.

The program began with a set of five songs by Samuel Barber. (A minor complaint about the program and that is that information beyond the title and poet for each song would be helpful, like a year and collection or opus number.) One of the great experiences of my course on Opera in the 20th Century this semester has been turning students on to Barber's Vanessa. Well, he was also a gifted miniaturist in song, too. Prior to this concert, I knew his happy-go-lucky setting of The Daisies (James Stephens), which provided an excellent start to the program, the somber With rue my heart is laden (A. E. Housman), and the darker Night Wanderers (W. H. Davies). However, I was introduced to two excellent songs to poems of James Joyce, Rain Has Fallen (which is an early song like the others) and the later, mysterious Solitary Hotel (the fourth song in Despite and Still, op. 41, 1968-1969). The text is a passage from Ulysses, and the strange scene it describes is accompanied by a twisted tango, as if in the background of the hotel lobby.

The second set began with John Duke's Richard Cory (E. A. Robinson) and Vittorio Giannini's Tell Me Oh Blue, Blue Sky, in which Hampson displayed his ppp head voice. This was followed by God Be in My Heart by Elinor Remick Warren, a composer who has particularly interested Mr. Hampson. In fact, producing one of Remick Warren's manuscript songs in a manila folder, he announced that he was adding to the program another of her songs, just recently discovered among the composer's papers donated to the Library of Congress. Not only had At Even (Thomas S. Jones, Jr.) not been published, it had never been performed, maybe not even heard by Remick Warren herself. As a tribute, Mr. Hampson gave the score a kiss as the audience applauded.

The third set included three songs on texts by Walt Whitman. The first was a miniature by Ned Rorem, As Adam Early in the Morning, a pretty, languorous wrapper for Whitman's homoerotic text. With Charles Naginski's powerful Look Down, Fair Moon Thomas Hampson moved me profoundly. It's a horribly tragic poem, and the setting is packed with emotional appeal, as is the biography of this poor composer, who after a less than satisfactory performance of a new work at Tanglewood, drowned himself in Lake Tanglewood. The last Whitman text was set by Henry T. Burleigh (Ethiopia Saluting the Colors). The first half concluded with Paul Bowles's Blue Mountain Ballads, four songs on poems by Tennessee Williams.

The second half of the concert began at 9:30 pm, which impelled some audience members toward the exit. This was their loss, since the second half was much shorter than the first and equally entertaining. The first two songs—Charles Griffes's An Old Song Re-Sung (John Masefield) and Edward MacDowell's The Sea (W. D. Howells, after Goethe), from Eight Love Songs, op. 47, from 1893—are both related to the ocean. Jazz-inspired sounds invaded the mostly traditional harmonic vocabulary of this recital for William Grant Still's lush, gorgeous Grief (LeRoy Brant) and Arthur Farwell's The Old Man's Love Song, one of the results of this composer's cataloguing of Native American folk song.

In the traditional crescendo ad finem of this sort of recital, Hampson saved some of the most rousing pieces for the conclusion, starting with Charles Ives's hysterically funny Memories (1897), which featured Hampson whistling and humming to great comic effect, as well as his accompanist shouting "Curtain!" Next, Walter Damrosch's rousing setting of Rudyard Kipling's Danny Deever, which Mr. Hampson credited as the favorite song of President Teddy Roosevelt, was balanced by the hushed setting of the traditional tune Shenandoah by Stephen White. To cut off the appreciatory applause for the latter, Hampson launched with no pause into his concluding piece, Aaron Copland's The Boatmen's Dance. A standing ovation earned us one encore, announced as "a World War I ballad you probably know but should probably hear more often," which turned out to be a sentimental rendition of Roses of Picardy. (Yes, the one that Perry Como used to sing.)

In spite of the mental lapses mentioned above, Thomas Hampson was in top form for this recital. If there was here and there a hint of vocal weariness, I think that the singer's schedule—the Kennedy Center Honors on Sunday night, not to mention singing the role of Wolfram in the Met's production of Tannhäuser on Saturday night and Thursday night—is to blame. His diction was so clear and never overbearing, so that I could understand every word but did not feel like I was being spit on. Hampson showed off his particularly full range of dynamic power and tonal color, and the man has an overpowering stage presence. I agree that he is an excellent ambassador for the cultural revival that he is preaching, and I wish him and the Library of Congress the best. The program was beautifully selected, truly a selection of the finest, although perhaps a bit monochromatic. If the most dissonant sounds in a program of American music are in works of Samuel Barber, you have probably not explored the full range of American compositional styles. This is not to say that I did not enjoy every moment of this repast of my national song, only that there are some other flavors on the spice rack.

NB: You can hear Thomas Hampson on the live Met radio broadcast of Tannhäuser on December 18, at

No comments:

Post a Comment