The Quatuor Ébène Between Salzburg and Washington

The Quatuor Ébène impressed audiences around the world, not the least since their winning the ARD Competition in 2004. In Washington Pierre Colombet (first violin), Gabriel Le Magadure (second violin), Mathieu Herzog (viola), and Raphaël Merlin (cello) last played in 2006 where they offered repertoire staples (Bartók, Haydn, Ravel) at the Corcoranand examples of their other passion – Jazz – at the Library of Congress. On March 6th, they will embark on their first big North American tour, starting in Boston, criss-crossing the country by hitting Oklahoma, Gainsville, Portland, Seattle, New York’s Carnegie Hall, and – fortunately – Washington DC at the Library of Congress on March 13th. Even for a town spoiled with great chamber music, this recital of Debussy, Fauré, and Ravel should be circled in all music enthusiasts’ calendars.

Meanwhile, on August 18th this year, they gave their Salzburg Festival debut at the gorgeous Large Concert Hall of the Mozarteum. Their last concert before a months worth of vacation, it was at first a nervous, then free-wheeling, and on the whole triumphant debut.

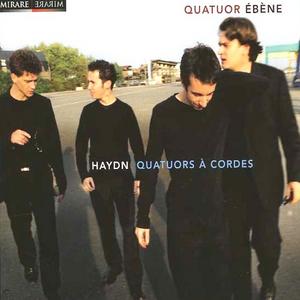

J.Haydn, 3 Quartets, Quatuor Ébène Mirare      B.Bartók, Quartets 1 - 3, Quatuor Ébène Mirare      A.Webern, A.Berg, A.Schoenberg, Langsamer Satz, Lyric Suite, SQ4t.#4, Quatuor Psophos Zig Zag     |

The searching first movement Lento of Bartók’s First String Quartet op.7 (1908, Szöllözy 40) doesn’t make it particularly easy to find one’s way into, but the ardor especially of the lower strings had the interested, if lamentably sparse audience engaged from beginning to end – when the quartet has reached the riveting Allegro vivace by way of (Allegro) Introduzione. From the very audibly cosseted Beethoven reminiscences right through the middle movement to the finale where Bartók’s freewheeling sprit and the “Peacock” folk-tune fly about and around our ears: This was an assault on all the senses in the most invigorating, stimulating way. If a quartet can’t let it rip during Bartók, then when?

During intermission a few people fled from Anton Webern’s name staring at them from the program. This might have been more understandable – though still lamentable – had the Quatuor Ébène programmed his String Quartet op.28 or Six Bagatelles op.9 which are admittedly ‘difficult’ listening. But on the menu was Webern’s Langsamer Satz (Slow Movement for String Quartet). The filigreed, high-romantic chromaticism is one of the most searing pieces of music ‘per square inch’ there is. It’s Tristan & Isolde condensed into 9 minutes. Magnificent the Ébène’s lush reading: a better case for Webern could scarcely have been made. Easily the highlight of this excellent recital, this was one of those examples where words fail and only music can continue to speak. The atmosphere of a whole hall collectively holding its breath during the most exquisite pianissimopassages alone elevated the recital to one of those rarest of moments that can instill, further, or restore one’s faith in music. Quiet ecstasy!

Back to earth for Ravel: a more gritty type of fun and joy – and the official twin of the Debussy Quartet. Not the elation of Webern or the exhaustive bursts of energy of the Bartók, but just the thing to deliver a kick and quicken one’s step on the way from the Mozarteum out into the awaiting Salzburg night. The first two movements were a display of the most nimble delicacy and wit, putting smiles on faces all around. The third movement was surprisingly dark and hovering, though lacking a little tension again. No matter: the Vif et agité finale ripped forth from their instruments like a bat out of hell. Instrument abuse in the service of music. This was music as entertainment – which is precisely what music is and what it should be. Three unconventional encores – Chick Corea’s “Spain”, Miles Davis’ “Kind of Blue”, and a Piazzola-esque rendition of the Pulp Fiction soundtrack underlined the aspect of brilliant entertainment.

Early October the Quatuor Ébène will issue their first recording on their new label, Virgin, with Fauré, Debussy, and Ravel.