Philip Glass, portrait by Chuck Close (left) and recent photograph (right) -- see the exhibit of Chuck Close portraits of Philip Glass in the Met lobby |

Arguably, the most significant difference to arrive with the Peter Gelb era at the Metropolitan Opera is a greater openness to contemporary opera (also the unforeseen success of the HD broadcasts, although that has had both positive and negative effects). Rather than a real step toward the future, however, the shift in favor of new operas, however slight, is actually a return to the great house's historical tradition, during the period that ended approximately with the premiere of Howard Hanson's Merry Mount. The repertorial concretization at the Met of recent years was actually a dangerous flirtation with provincialism, meaning that the wealthiest American company was regularly being upstaged by smaller, more adventurous outfits like Santa Fe Opera, in terms of world premieres and American premieres.

As a result, the recently opened production of Philip Glass's Satyagraha was a cause for celebration, and critics descended from far and wide for opening night last week (including Washington's own Tim Page, who spoke eloquently on the Sirius broadcast) to witness the Met turning this important page (next season will have Adams's Doctor Atomic, reportedly with The Ghosts of Versailles and Golijov's new Daedalus to follow). Ionarts was able to get there for the third performance of the run, Saturday's matinee.

As a result, the recently opened production of Philip Glass's Satyagraha was a cause for celebration, and critics descended from far and wide for opening night last week (including Washington's own Tim Page, who spoke eloquently on the Sirius broadcast) to witness the Met turning this important page (next season will have Adams's Doctor Atomic, reportedly with The Ghosts of Versailles and Golijov's new Daedalus to follow). Ionarts was able to get there for the third performance of the run, Saturday's matinee.

The Met's first and, until now, only experiment with Philip Glass, the 1976 performance (not really production) of Einstein on the Beach, was a watershed event in opera history. That work, more experimental theater than real opera, is often described as a one-time test case, but Satyagraha, premiered only four years after Einstein, has much more in common with its predecessor than not. Its libretto (in Sanskrit -- it may as well be numbers and solfege syllables, in terms of audience comprehension), adapted by the composer and Constance DeJong from texts in the Bhagavad-Gita, does not actually tell the story of its purported subject, the years that Gandhi spent in South Africa. The audience is required to familiarize itself with that story beforehand, and the tableaux of stage action refer to it and connect it with other stories, both ancient and modern, religious and secular.

Satyagraha, Metropolitan Opera, 2008, photo by Ken Howard |

The work's title indicates that the opera is not really about its central character, Gandhi, at least not exclusively. Satyagraha, a Sanskirt word usually translated as "truth force," is how Gandhi described his tactic of nonviolent protest, and three historical figures who influenced it or were influenced by it (Leo Tolstoy, Rabindranath Tagore, and Martin Luther King, Jr.) look down on the three acts like guardian angels. The paradox of the work is that it sprawls so widely, passing without borders from mythology to the modern and back again, and yet does so immersed in an enveloping stasis. There may be more of an actual story than Einstein, at least in the background, but the process of relating it -- or not relating it, perhaps -- is remarkably similar.

Other Reviews:

Ronald Blum, Glass' 'Satyagraha' Reaches Met (Associated Press, April 13)

Anne Midgette, 'Satyagraha': Simplicity & Splendor in the Glass (Washington Post, April 14)

Anthony Tommasini, Fanciful Visions on the Mahatma’s Road to Truth and Simplicity (New York Times, April 14)

Daniel J. Wakin, Puppets enliven Metropolitan production of opera 'Satyagraha' (International Herald Tribune, April 14)

Jeremy Eichler, Gandhi at the Met, Glass in transition (Boston Globe, April 14)

Mark Swed, Live: 'Satyagraha' (Los Angeles Times, April 14)

Patrick Cole, Selling Gandhi, Glass: `Satyagraha' Uses Posters, Yoga Teachers (Bloomberg News, April 16)

Tim Smith, Glass' hypnotic opera at Met (Baltimore Sun, April 17)

Vibhuti Patel, Gandhi’s Wonder Years (Newsweek, April 17)

Heidi Waleson, History and Hypnotic Magic (Wall Street Journal, April 19)

Karren L. Alenier, Satyagraha (Culture Vulture, April 20)

Other Articles:

Matt Blank and Stephen Kent, Satyagraha: Can Opera Help Fight Climate Change? (Playbill Arts, April 3)

Elena Park, Metropolitan Opera: The Force of Truth (Playbill Arts, April 11)

---, Philip Glass: The Message in the Music (Playbill Arts, April 21)

David Cote, Puppet Regime (Opera News, April 2008) |

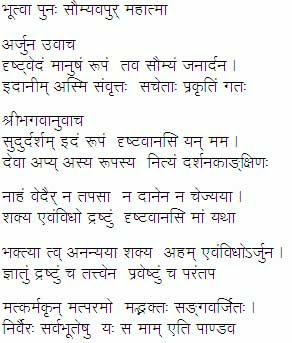

This performance is anchored by the astounding interpretation of tenor Richard Croft as Gandhi. Whenever Glass's score was metered unevenly, the other singers seemed to be changing notes more on the cues of the conductor than on a sure internal pulse. Croft was not only rock solid from his first note (unaccompanied, he opens the opera, just after he has been famously thrown from a train), no matter how complex the rhythms, but his line always sounded like a melody, lyrical and flowing. Conductor Dante Anzolini had his work cut out for him, keeping the complicated and regularly changing meter with one hand, cuing all of those singers' entrances and cutoffs with the other, and even mouthing words to the chorus. That Anzolini was able to keep the largest parts of the score together at all was remarkable. When the chorus, after a solid start in the indelibly memorable Ha-Ha scene of Act II, began to rush, however, he was not able to retain control.

All members of the supporting cast are to be congratulated for surviving the score's grueling demands, especially soprano Rachelle Durkin (Miss Schlesen) who sang so many high notes again and again (not always right where they needed to be, but still), it was hard to keep track. Of the quartet that often sings together, baritone Earle Patriarco (Mr. Kallenbach) was the most consistently impressive. As Parsi Rustomiji, bass-baritone Alfred Walker was too easily covered by other sounds when he was anywhere but near the apron. Mezzo-soprano Mary Phillips had a grand presence as Mrs. Alexander, the wife of the regional governor, who protects Gandhi with her umbrella. Phelim McDermott's direction emphasized statis, sapping all of the personality from the characters, as they mostly stood in place or walked in slow motion with no impetus or direction.

The production, which comes to New York from English National Opera, is beautiful, monumental, and puzzling. Julian Crouch's set is a raked stage surrounded by a ring wall of nondescript color, and the largely monochromatic costumes designed by Kevin Pollard follow the course of Glass's score, towards a more and more austere set of colors. Thankfully, an element of whimsy and menace was added by the puppeteers and supernumeraries of the Improbable Theatre Company, the only thing that saved Glass's ponderous, philosophical opera from its own sententious seriousness. Most of the evening's visual souvenirs involved the puppeteers, creating a halo for Richard Bernstein's Lord Krishna, crumpling newspapers to form heads and limbs, flying on wires, manipulating the over-sized capitalist goons behind the Ha-Ha chorus in Act II and the giant bird puppet, and unrolling undulating bands of packing tape across the stage.

Satyagraha, Metropolitan Opera, 2008, photo by Ken Howard

Eventually, one gives up caring about the words being sung, as the text just flows over the listener (in spite of the beautifully realized projections). Someone should make a video like the Carmina Burana with alternate lyrics, with the Sanskrit of Satyagraha replaced with nonsense (beginning with "Raja, naba do wa, gola wookie, nipple pinchie?," the gibberish spoken by Jaba the Peter in Family Guy). This Buddhistic relinquishing of conscious comprehension is likely part of Glass's strategy in the third act, where he prolongs the plainest music (all those endless unison string arpeggios!) to separate the listener from harmonic expectations. That austerity sets up the memorable conclusion, with Gandhi repeatedly intoning that ascending phrygian scale (heard earlier, in the flute, in the first act) over more complex orchestral textures that blossom in the final bars.

The production of Satyagraha, which is an event not to be missed, continues for four more performances (April 22, 25, 28, and May 1), at the Metropolitan Opera in New York.