Summer Opera: Ainadamar in Santa Fe

Sadly for me, I had to leave New Mexico before the big-time premiere of Osvaldo Golijov's one-act opera Ainadamar, revised for Santa Fe Opera after being performed at Tanglewood and by the Los Angeles Philharmonic. Well, the premiere was Saturday night, and the big boys are starting to weigh in on it. Starting with the biggest of the big, Bernard Holland was there to review the opera (Haunted by the Deaths of Martyrs, a Century Apart, August 1) for the New York Times:

Sadly for me, I had to leave New Mexico before the big-time premiere of Osvaldo Golijov's one-act opera Ainadamar, revised for Santa Fe Opera after being performed at Tanglewood and by the Los Angeles Philharmonic. Well, the premiere was Saturday night, and the big boys are starting to weigh in on it. Starting with the biggest of the big, Bernard Holland was there to review the opera (Haunted by the Deaths of Martyrs, a Century Apart, August 1) for the New York Times:

The dead and dying appear in layers, one layer bleeding into the other. Blended too is Spain's darker side, with its dignity and repressed violence, and that same soul transplanted to Latin America, now invested with the garish and the lugubrious. In Mr. Golijov's music, flamenco and its Phrygian melody blare through amplification; so too do Afro-Cuban pounding and delicate Caribbean dance rhythms. Like his fellow Argentinean Astor Piazzolla, Mr. Golijov does not harness popular music; he liberates it. The energy is freed from a simple dance band function and allowed to wander into modulating keys and new meters. This is "low art" arranged in sophisticated sentences. Some of the close-harmony singing might come from a Xavier Cougat movie. Mr. Golijov takes his brass fanfares from the bullring and his sentimental moods off any old record or sheet music he can find. He is not afraid to get his hands dirty.Now this may sound like hitting below the belt, pulling out that "low art" card, but compared to the savaging Golijov's opera received at its Tanglewood premiere, this is a rave. To give you an idea of how a full-force lunge for the vitals looks on paper, here are a few choice excerpts from Holland's colleague, Anthony Tommasini (New Operas Remember The Agony Of Lovers Left Behind, August 13, 2003), for the New York Times:

Given Mr. Golijov's high promise and enormous gifts, his one-act opera "Ainadamar" was a major disappointment. He has conceded in recent interviews that he was late in composing this 70-minute score and that it had the earmarks of a rush job. [...] Though dramatic events occur in the opera, the story itself is a recollection and lacks narrative tension. This would be no problem, if there were more tension in the music. In places you hear palpable evidence of Mr. Golijov's great skills: some duets for the older and younger Margarita in which ruminative vocal lines are enshrouded by hazy, luminous, bittersweet orchestra harmonies; some playful song-and-dance numbers for the women's chorus sung with an intentionally nasal Latin American twang. And there are brilliant episodes of taped music: when the sounds of gurgling water and galloping horses are terrifyingly merged, and when the rifle shots that take down García Lorca are turned into crazed rhythmic volleys.

But whole patches of the score sound like generic Latinized vamping. Over droning pedal tones, slinky minor-mode melodies in the strings or voices spin and turn, film-scorish music that makes a big deal out of prolonging the half-step dissonance before the melody resolves into the tonic pedal tone. And an early episode of percussion in which the players break into hand-clapping makes you think of the Copacabana band.

Philip Kennicott, 'Ainadamar': Agony And Ecstasy in Santa Fe (Washington Post, August 15) George Loomis, Ainadamar, Santa Fe Opera (London Financial Times, August 10) Anne-Carolyn Bird, Political (The Concert, August 3) Mark Swed, Out of failure, a new victory (Los Angeles Times, August 2) Chris Shull, Revolutionary music: Harth-Bedoya conducts 'Ainadamar' on opening night (Ft. Worth Star-Telegram, August 1): the conductor in Santa Fe, Miguel Harth-Bedoya, is music director of the Fort Worth Symphony Alex Ross, Deep Song: Ainadamar (The New Yorker, Sept. 1, 2003) |

Dramatically, the first 20 minutes felt like an eternity of exposition. Matters weren't helped by the chorus members' inconsistent group movements; it was impossible to tell if they were deliberately acting as individuals rather than a welded ensemble or hadn't gotten cues into their bones as well as their heads. It contrasted strongly with their rock-solid singing. [...] The new ending was tonally lovely but meandered on without resolution. In fact, the 75-minute opera could be cut to 60 minutes to real benefit. As it stood, Saturday's reading felt like something a choral society had tried to stage without every member being present, despite Sellars' generally telling direction. Considering that rewrites were still going on so close to opening, that's not much of a surprise. It will be instructive to see how the piece shapes up as it shakes down.Happily for me, after I met with blogging soprano Anne-Carolyn Bird for coffee on my last day in Santa Fe (last Monday), she was kind enough to invite me to that evening's rehearsal, with sets and costumes, but only piano, guitar, and percussion, not full orchestra. (Anne-Carolyn has performed the work in its previous incarnations, both at Tanglewood and in L.A.) What follows are some thoughts on the opera, although these comments are not really a review, since what I witnessed was a rehearsal.

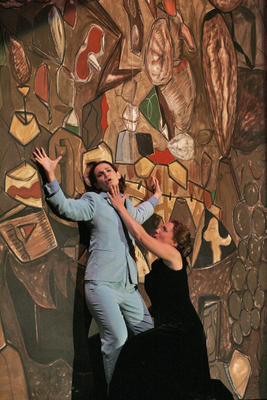

The set (not mentioned much in the reviews I've read so far), painted in a one-man tour de force this spring by Gronk, is a thing of beauty, consisting of a series of back panels that slide away to reveal the night vista at the end of the opera, two full side walls that angle out toward the audience, and the floor. Gronk is known especially for his urban murals, although his influences range from high-art expressionism to graffiti and folk mural (here is a sampling of images of his work). Gronk was in the house on the night of the rehearsal that I heard and seemed involved in the production as it progressed toward opening night. What he has created is an ideal dreamscape for this opera's unusual story, a series of events that could not actually occur. While it is perhaps not as unreal as Einstein on the Beach, for example, the libretto (written by David Henry Hwang in English and translated by Golijov into Spanish) is at the far end of the less traditional for opera. The story is about remembering and imagining, not about living. Lorca's play, Mariana Pineda, was premiered with sets designed by Salvador Dalí (with whom Lorca was infatuated at the time). Since that play figures so prominently in the opera, it struck me as a great idea to have abstract painting as the backdrop.

The set (not mentioned much in the reviews I've read so far), painted in a one-man tour de force this spring by Gronk, is a thing of beauty, consisting of a series of back panels that slide away to reveal the night vista at the end of the opera, two full side walls that angle out toward the audience, and the floor. Gronk is known especially for his urban murals, although his influences range from high-art expressionism to graffiti and folk mural (here is a sampling of images of his work). Gronk was in the house on the night of the rehearsal that I heard and seemed involved in the production as it progressed toward opening night. What he has created is an ideal dreamscape for this opera's unusual story, a series of events that could not actually occur. While it is perhaps not as unreal as Einstein on the Beach, for example, the libretto (written by David Henry Hwang in English and translated by Golijov into Spanish) is at the far end of the less traditional for opera. The story is about remembering and imagining, not about living. Lorca's play, Mariana Pineda, was premiered with sets designed by Salvador Dalí (with whom Lorca was infatuated at the time). Since that play figures so prominently in the opera, it struck me as a great idea to have abstract painting as the backdrop.Director Peter Sellars is responsible for the reshaping of the opera, which takes the work in a more politicized direction (for this impression, I rely on people who are familiar with both versions). There is a striking dichotomy between the artistic side of this opera, the group of feminine voices (Lorca, Margarita Xirgu, the ensemble), and the military, male side, represented especially in the character of the arresting officer, Ruiz Alonso. Standing at the back of the stage through most of the action, sometimes smoking a cigarette, he is a menacing presence, costumed in army camouflage, buzz cut, boots, and machine gun. Golijov's writing for this part is loud and high: in his review of the Tanglewood premiere, Alex Ross compared the vocal writing for this part to a muezzin's cantillation, which is exactly how I would have described it. Tenor

Ruiz Alonso, whose costume recalled for me, at least, the clothing of an American soldier, representing the misguided forces of fascism, controlling the life and death of prisoners brought to Ainadamar (from Arabic for "fountain of tears"), where thousands of perceived enemies of the state were imprisoned and then summarily executed. Although none of the review that have appeared yet made any comment on the revised opera's political message, the comparison between the Spanish fascists and the Bush administration was made more pronounced by the loudspeaker broadcast of a speech (I believe it was Franco, although Lorca was executed by nationalist forces before Franco officially came to power), heard twice, that included a phrase translated as "Those who are not with us are against us. Long live death!" The message is that we, the government, authorize you to use whatever force you think is necessary. (This is how we end up at Guantanamo Bay and Abu Ghraib. Let us not forget that Franco claimed the power he had on the basis of "emergency war powers.") In the conclusion of the opera, much changed, there is a beautiful trio ensemble (Nuria—Margarita's student—Margarita, and Lorca), during which Lorca's spirit kisses Margarita and thanks her for keeping his plays alive. When Margarita dies, the female ensemble leaves the stage through the parting back panels into the darkness, and the rear section of the stage raises them upward. At this point, Margarita stands up and confronts the soldier, whom she "watched" kill Lorca, with the words "Yo soy la libertad" (I am freedom), repeated over and over again. It is a hopeful political message.

Lorca's story and the Spanish civil war, in general, are still taboo topics in much of Spain. You may remember the controversy last year over whether the mass grave (what they call in Spain the "graves of forgetting") where Lorca was buried could be disturbed to exhume the bodies of the victims. There was a good article about it in The New Yorker, which I cannot locate (in spite of greg.org's helpful database). No one wants to be reminded of a time when a large part of your society allowed terrible things to happen. One of the goals of Sellars's reshaping of Ainadamar, it seemed to me, was to make us think about just that, right now.

As I said, the rehearsal I heard was not with full orchestra, but I got the impression of the massive waves of sound, both recorded and live, that Golijov was trying to create. That volume, plus the occasional strange or distant placement of singers, meant that all singers were amplified by body mikes, which I didn't like but understood. Dawn Upshaw (Margarita Xirgu, the experimental actress and theater director who was Lorca's muse) gave a dramatically riveting performance, adjusting her singing well to fit the microphone. Her horrible death seizures were terrifying to watch. Although Kelley O'Connor (Lorca) lists herself as a mezzo-soprano, she has a rich, incredibly deep voice that is quite unusual. The part that Golijov wrote might seem to call for an unclassifiable vocal freak (in the best sense of that phrase), a woman singing often in the male range, and the difference with the high, clear sopranos of Upshaw and Jessica Rivera (Nuria, Margarita's student) made for great ensemble writing. Dance rhythms permeate the musical fabric, as well as some recorded sounds, and sometimes the two intermingle, as in the grotesquely balletic execution scene (the three victims are shot in order, over and over again), where the sound of gunfire becomes a drum beat. Golijov's style is somewhat static and monochromatic but terribly effective.

After Santa Fe, Ainadamar will be performed at Lincoln Center in January 2006, as part of a Golijov festival. His breakthrough work, La Pasión Según San Marcos, will also be performed for that festival, in February. Ionarts is hoping to be there.

No comments:

Post a Comment