Briefly Noted: Bolcom's Complete Rags

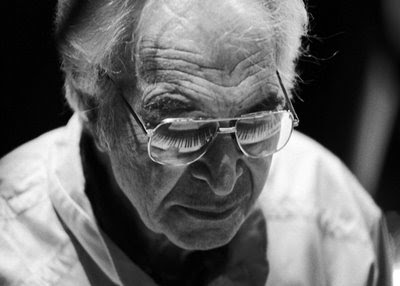

William Bolcom, The Complete Rags, Marc-André Hamelin (released on June 3, 2022) Hyperion CDA68391/2 | 133'03" |

Marc-André Hamelin, himself a musical mimic not unlike Bolcom, gives these pieces a studied nonchalance. The two discs obviously include everything published in Bolcom's Complete Rags collection twenty years ago, with a couple of charming lagniappes. These include a few late arrivals, like Knockout 'A Rag', from 2008, in which the player raps on the piano's fallboard for a cool percussive self-accompaniment (an effect heard less extensively in the earlier Serpent's Kiss, with a bit of whistling, too), Estela 'Rag Latino' (2010), and what Bolcom thinks will be his last rag, the ultra-serene Contentment (2015). Another curiosity to discover is Brass Knuckles, a 1969 collaboration between Bolcom and another composer, William Albright, in imitation of the "collaborative rags" undertaken by Joplin and other rag composers.

The spirit of innovation runs through this music, as Bolcom merges the gestures of ragtime with other kinds of music, from more dissonant modernism to Latin genres as in the Tango-Rag. Bolcom also describes his 1969 meeting with the octogenarian Eubie Blake, the great stride master, a style Bolcom calls "urbanized ragtime." They became friends and performed together, a musical relationship that ran deep: "I consider him my last great teacher," Bolcom notes. As if to acknowledge that debt, the recording opens with Eubie's Luckey Day, a tribute to Blake's Charleston Rag.