Best Recordings of 2018

Time for a review of classical CDs that were outstanding in 2018 again! This lists the new releases with the best re-issues following below.

Preamble

It’s fair to say to say that such "Best-Of" lists are inherently daft if one clings too literally to the idea of "Best." Still, I have been making "Best of the Year" lists for classical music since 2004 (when working at Tower Records gave me a splendid oversight—occasionally insight—of the new releases and of the re-releases that hit the classical music market. Since then, I’ve kept tabs on the market as much as possible. Here are the links to the past iterations on ionarts and Forbes.com:

2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2008—"Almost" | 2009 | 2009—"Almost" | 2010 | 2010—"Almost" | 2011 | 2011—"Almost" | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017

Making these lists is a subjective affair, aided only by massive exposure and hopefully good ears and discriminating, if personal taste. But then "10 CDs that, all caveats duly noted, I consider to have been outstanding this year" does not make for a sexy headline. You get the point. The built-in hyperbole of the phrase is a tool to understand what this is about, not symbolic of illusions of grandeur on my part. As has been my tradition, there are two lists: One for new releases and one for re-issues. And because there is a natural delay between the issuing date of a recording and my getting to listen to it, the cut-off date for inclusion in this list is roughly around September 2017. (In a way that’s good, because going back a little further softens the recency-bias that these lists can otherwise suffer from.) And here, without further ado, are "The 10 Best Classical Recordings Of 2018".

# 10 - New Release

L.v.Beethoven, Symphony No.3 (+ R.Strauss, Horn Concerto), Manfred Honeck, Pittsburgh Symphony, Reference Recordings FR-728SACD

L.v.Beethoven, Symphony No.3 (+ R.Strauss, Horn Concerto), Manfred Honeck, Pittsburgh Symphony, Reference Recordings |

# 9 - New Release

R.Schumann, "Frage" – select Lieder, Christian Gerhaher & Gerold Huber, Sony 19075889192

R.Schumann, "Frage" – select Lieder, Christian Gerhaher & Gerold Huber, Sony |

# 8 - New Release

J.S.Bach, Cantatas BWV 56, 95, 161, Rudolf Lutz, soloists, Bach Stiftung Orchestra & Chorus, Bach Stiftung B667

J.S.Bach, Cantatas BWV 56, 95, 161, Rudolf Lutz, soloists, Bach Stiftung Orchestra & Chorus, Bach Stiftung |

# 7 - New Release

Kenneth Fuchs, Piano Concerto, Saxophone Concerto, E-Guitar Concerto, Poems of Life, JoAnn Faletta, London Symphony Orchestra, Jeffrey Biegel (piano), T.McAllister (sax), D.J.Spar (guitar) et al., Naxos 8.559824

Kenneth Fuchs, Concertos & Songs, JoAnn Faletta, London Symphony Orchestra, Jeffrey Biegel (piano), T.McAllister (sax), D.J.Spar (guitar) et al., Naxos |

The lede is the Piano Concerto (Jeffrey Biegel on the ivories), which covers several pleasant universes of sound in its three movements: From Ravel via "Lady Macbeth trombone" glissandi to Coplandesque moments and well beyond, it never quite lets you drift and always makes your ears perk. Glacier, the serenata-like Concerto for Electric guitar (D.J.Sparr) and Orchestra, is every bit as interesting as the Piano concerto – with moments that remind, successively, of John Scofield and Terje Rypdal. This is in turn followed by the easy listening (in the best sense) Concerto for Alto saxophone (Timothy McAllister) and Orchestra with a hint, almost inevitably, of Gershwin. The orchestral songs Poems of Life for countertenor (Aryeh Nussbaum Cohen) and orchestra take a little longer to get used to in the surrounding context of the concertos, but eventually they, too, fit into the mold of harmonious tanginess that Fuchs casts for his works.

The performances easily do enough to reveal the music’s beauty and clever fun. Conductor JoAnn Faletta navigates the hired London Symphony Orchestra through the music without accidents. We don’t have Manfred Honeck, Teodor Currentzis and Kyrill Petrenko standing in line to make Kenneth Fuchs recordings any time soon (not that we should want to rule it out), so we’ll take what we get and am grateful it’s as good as it is.

# 6 - New Release

R.Schumann & J.Widmann, "Es war einmal…" – Märchenerzählungen op.132, Fantasy Pieces for Clarinet and Piano op.73, Märchenbilder for piano and viola op.113 & "Once Upon A Time… Five Pieces in Fairy Tale Mood for clarinet, viola and piano, Dénes Várjon (piano), Tabea Zimmermann (viola), Jörg Widmann (clarinet), Myros Classics MYR020

R.Schumann & J.Widmann, "Es war einmal…", Dénes Várjon (piano), Tabea Zimmermann (viola), Jörg Widmann (clarinet), Myros |

If you are an inveterate Schumann lover, however, (or well on your way thereto), this is actually the continuation of the thrilling Schumann Violin Sonata recording of Varjon’s with Carolin Widmann that appeared on ECM and should have been high in my Best of 2009. The deliciously near-late Schumann, a dream of hazy, woven textures, was written between 1849 and 1851 and is here performed with sensitivity, intimacy (especially thanks to Várjon and Zimmermann), and expressive richness that gives the lightly forlorn music a haptic, certainly sensual quality: A winner of a disc, either – depending on your musical leanings – with a caveat or a bonus.

# 5 - New Release

P.I.Tchaikovsky, Symphony No.6 ("Pathétique"), MusicAeterna, Teodor Currentzis, Sony 88985404352

P.I.Tchaikovsky, Symphony No.6 ("Pathétique"), MusicAeterna, Teodor Currentzis, Sony |

The impression he left was certainly visceral: "All smiles, with long bobbed hair, and India-rubber limbs, Currentzis looks like a master of ceremonies at MIT’s Harry Potter convention. An enthusiastic image, and a slightly ridiculous one." But it was also musically positive: "Under his hands, the side-by-side of Prokofiev’s children-like naïveté [in the Seventh Symphony], his veteran assuredness and deft rhythmic handling sounded perfectly organic. And the orchestra went along well enough, especially considering this was the first night of the run. As a little treat, Currentzis played the symphony with both alternate endings: the quiet original first, and then, after a little pause, the few bars of upbeat compromise that Prokofiev grudgingly added." (ionarts: The Currentzis Dances) Since then, I’ve seen and heard him blow the roof off the Vienna Konzerthaus… a conductor that has fully grown into the hype around him – and capable of achieving novel, intriguing, insightful results with guest orchestras just the same, not just his own band where he has unrivaled, dictatorial-in-the-service-of-music conditions that no other place could offer him. He’s controversial – but the real deal.

Point in case his Tchaikovsky Sixth Symphony released late last year. (You could almost equally insert his new Mahler Sixth in this spot; it might well hop onto next year’s list.) This is a recording at once stunningly superficial and stunningly absorbing. The attention to detail, the obsession, the fine-tuning – even the overproducing – are all audible… but unlike many a micro-managing conductor, the whole does not descend into technically impressive boredom. It remains visceral, exciting. Currentzis’ Pathetique is the exact opposite of the liquid, golden honey that flows from the baton of Semyon Bychkov and his Czech Philharmonic in the same work (released around the same time – and superb in its own way!) This is a self-propelling nano-technology-beast, shimmering—ever-moving—in the sun in ever-changing colors. A thrill not to be missed, unless one is positively cemented into a purist/traditionalist position.

# 4 - New Release

I.Stravinsky, Chant funèbre, Le Faune et al Bergère, The Rite of Spring, Scherzo fantastique, Feu d’artifice, Riccardo Chailly, Lucerne Festival Orchestra, Decca 483 2563

I.Stravinsky, Chant funèbre, Le Sacre et al., Riccardo Chailly, Lucerne Festival Orchestra, Decca |

# 3 - New Release

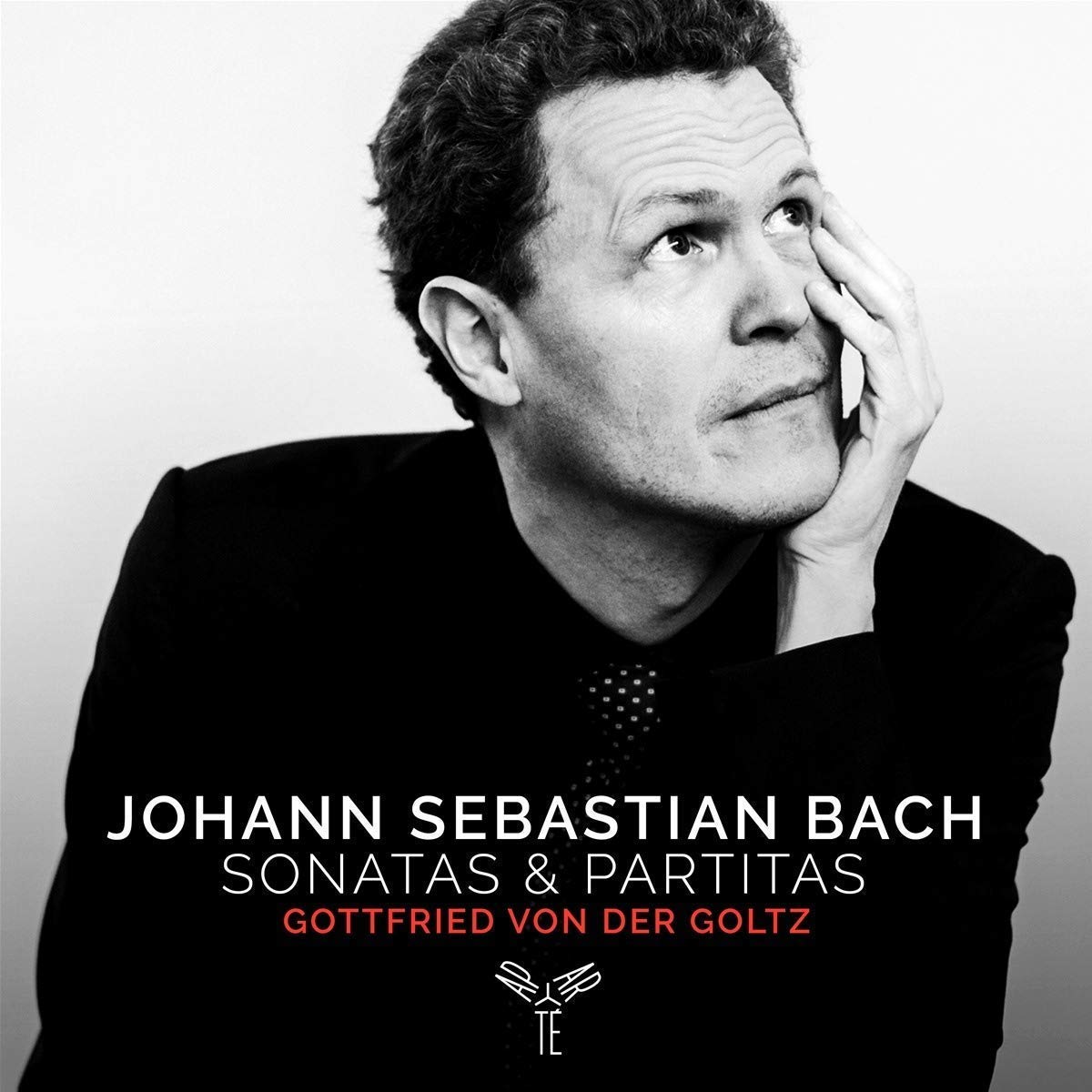

J.S.Bach, Sonatas and Partitas for Solo Violin, Gottfried von der Goltz, Aparté AP176

J.S.Bach, Sonatas and Partitas for Solo Violin, Gottfried von der Goltz, Aparté |

# 2 - New Release

B.Martinů, Bouquet of Flowers (+ Jan Novák, Philharmonic Dances), Tomáš Netopil, Prague RSO, Supraphon SU 4220

B.Martinů, Bouquet of Flowers (+ Jan Novák, Philharmonic Dances), Tomáš Netopil, Prague RSO, Supraphon |

A collection of seven vignettes and an overture, Bouquet of Flowers is a highly effective drama (or series of mini-dramas) written for orchestra, soloists, and choruses and intended for radio broadcast. It is constantly enchanting and entrancing music, even if the words of Karel Jaromír Erben’s poems – the famous collection "A Bouquet of Folk Legends" – remain foreign to your ear. The singers and the orchestra – the Prague Radio Symphony Orchestra under the youngish Tomáš Netopil – indulge in this music with something that sounds like total conviction. This is the ‘lesser’ among the established orchestras in Prague – and you’d never guess it.

(Full review on SurprisedByBeauty.org)

# 1 - New Release

F.Martin, Die Weise von Liebe und Tod des Cornets Christoph Rilke, Fabio Luisi, Philharmonia Zurich, Okka von der Damerau, Philharmonia PHR 0108

F.Martin, Die Weise von Liebe und Tod, Fabio Luisi, Philharmonia Zurich, Okka von der Damerau, PHR |

Frank Martin’s entrancing tone poem for contralto and orchestra was written while the war raged outside Switzerland – and perhaps therefore has a decidedly unheroic, melancholy touch to it. There’s a bittersweet beauty to the music, a bit like the sour and bitter but satisfying lingering of pure chocolate. Fabio Luisi, who seems never to have been more at home in a post than at the Zurich Opera and with its Philharmonia Zurich, provides the keenly felt, sensitive musical painting for the backdrop upon which Okka von der Damerau gives one of the most striking vocal performances I have heard on disc in a long time. With calm radiance she makes you take every step with the protagonist. The result is, in a word, ravishing.