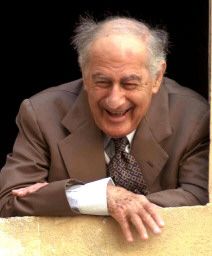

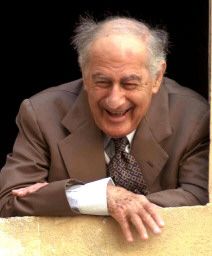

The death of composer Gian Carlo Menotti, at age 95 in Monaco on February 1, could hardly have escaped anyone's notice. Tributes, of a length rarely seen for a classical composer, have been published in a startling number of news sources around the world, mostly in English: The Times, BBC, New York Times, Washington Post, Bloomberg News. None of the major French dailies have published an obituary. Bloggers, too, have chimed in, including Alex Ross, Daniel Felsenfeld, and Opera Chic. Menotti spent a lot of time here in Washington, premiering some of his operas and in other ways, connections that are detailed in Tim Page's tribute in the Post. Not least, Menotti composed a late work, Goya, at the request of Plácido Domingo, premiered here in 1986.

The death of composer Gian Carlo Menotti, at age 95 in Monaco on February 1, could hardly have escaped anyone's notice. Tributes, of a length rarely seen for a classical composer, have been published in a startling number of news sources around the world, mostly in English: The Times, BBC, New York Times, Washington Post, Bloomberg News. None of the major French dailies have published an obituary. Bloggers, too, have chimed in, including Alex Ross, Daniel Felsenfeld, and Opera Chic. Menotti spent a lot of time here in Washington, premiering some of his operas and in other ways, connections that are detailed in Tim Page's tribute in the Post. Not least, Menotti composed a late work, Goya, at the request of Plácido Domingo, premiered here in 1986.

Menotti was a consummate man of the theater, and he should be remembered for many accomplishments. Most importantly, he opened up new vistas for opera composers, most successfully with Amahl and the Night Visitors (1951), the first opera composed specifically for performance on television (sadly, a trend that has not gone anywhere). One of his greatest accomplishments was not even in composition, but in writing the libretto for Samuel Barber's American masterpiece, Vanessa, which should qualify, as Tim Page put it, as Menotti's third Pulitzer Prize.

One of the things that Menotti did was to continue to open up the suitable territory for operatic subjects. Why could operas not be about everyday things that happen to everyday people? He based the characters in his early work

Amelia Goes to the Ball on people he met at dinner parties. (The Met picked up this opera for performance after it was premiered at the Curtis Institute in Philadelphia in 1937 -- those were the days.)

The Medium relates the story of a bullshit artist who makes a living as a spiritualist, and in

The Telephone, a man tries to propose to his girlfriend but is constantly interrupted by telephone calls.

In an attempt to find a middle way between the American musical and opera, those last two operas were presented as a double bill in a Broadway theater. Perhaps his greatest opera and certainly my favorite,

The Saint of Bleecker Street, for which he won his second Pulitzer, was also premiered on Broadway. That opera, as well as the equally tragic and menacing

The Consul, for which Menotti won his first Pulitzer, should put the lie to any accusations sometimes advanced, that Menotti was a lightweight or really only a Broadway composer. He will be missed.