Musicians from Marlboro I

Mozart, String Quintets, Talich Quartet, K. Rehak (La Dolce Volta, re-released in 2012) |

Washington Post, October 9

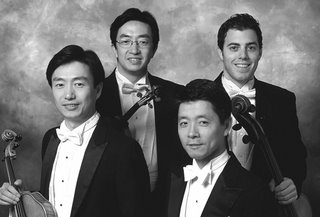

The touring concerts from Vermont’s Marlboro Music Festival returned to the Freer Gallery of Art on Thursday night. The three works heard at this concert all feature unusual chamber music combinations, made more feasible by the festival’s variable programming format, with so many musicians on hand each summer.Musicians from Marlboro I

“By general consent,” wrote pianist Charles Rosen, “Mozart’s greatest achievement in chamber music is the group of string quintets with two violas.” The doubling of Mozart’s beloved viola opened a vista of greater contrapuntal possibilities. The last of the set, K. 614, is also the final piece of chamber music that Mozart composed, not long before his death in 1791. Lead violist Rebecca Albers gave a lovely plangency to her part’s solo moments, while first violinist Hye-Jin Kim played with an occasionally unpleasant stridency that led to minor intonation problems. The group brought out the details of Mozart’s final tribute to Haydn in this piece, especially the folksy, drone-ridden trio of the third movement and the droll starts and stops of the finale.

Discovering the “Three Poems in French” for soprano and string quartet by Earl Kim (1920-1998) made me want to hear more from this Korean American composer. Soprano Hyunah Yu’s beautiful but slender voice allowed her to fit into and at times hide within the tightly coiled clusters and repeated motifs of the strings.

Pianist Kuok-Wai Lio brought technical polish to Fauré’s first piano quartet (C minor, Op. 15), keeping his cool even in the head-spinning finale. The second violinist and violist from the Mozart took the lead parts here, with violinist Danbi Um especially producing graceful, understated sound.

The second and third installments of the Musicians From Marlboro series will be held at the Library of Congress (Jan. 20 and May 6), because the Freer will be closed to the public starting in January.

Music by Mozart, Kim, Fauré

Freer Gallery of Art

SEE ALSO:

Vivien Schweitzer, Musicians From Marlboro, With Works by Mozart and Fauré (New York Times, October 6)