Briefly Noted: Tetzlaff siblings play Brahms Double (CD of the Month)

Brahms, Double Concerto / Viotti / Dvořák, Christian Tetzlaff, Tanja Tetzlaff, Deutsches Symphonie-Orchester Berlin, Paavo Järvi (released on October 1, 2023) Ondine ODE1423-2 | 60'43" |

Brahms wrote this piece very late in life, for cellist Robert Hausmann and his old friend Joseph Joachim. At that point Brahms and Joachim were no longer on speaking terms, as Brahms had "gone with" (as Larry David put it) Joachim's ex-wife following their divorce. In a gesture of friendship, Brahms meant the piece as a reconciliation, even including a varied form of the F-A-E motif he had used in the movement of the collaborative sonata dedicated to Joachim 30 years earlier. The Tetzlaffs' rendition of the slow movement is especially free and elegiac. Järvi excels at keeping the musicians of the Deutsches Symphonie-Orchester Berlin together with the soloists, giving them room rhythmically and with careful dynamics. The third movement could perhaps be more daring from the soloists, but it has a fine seriousness about it.

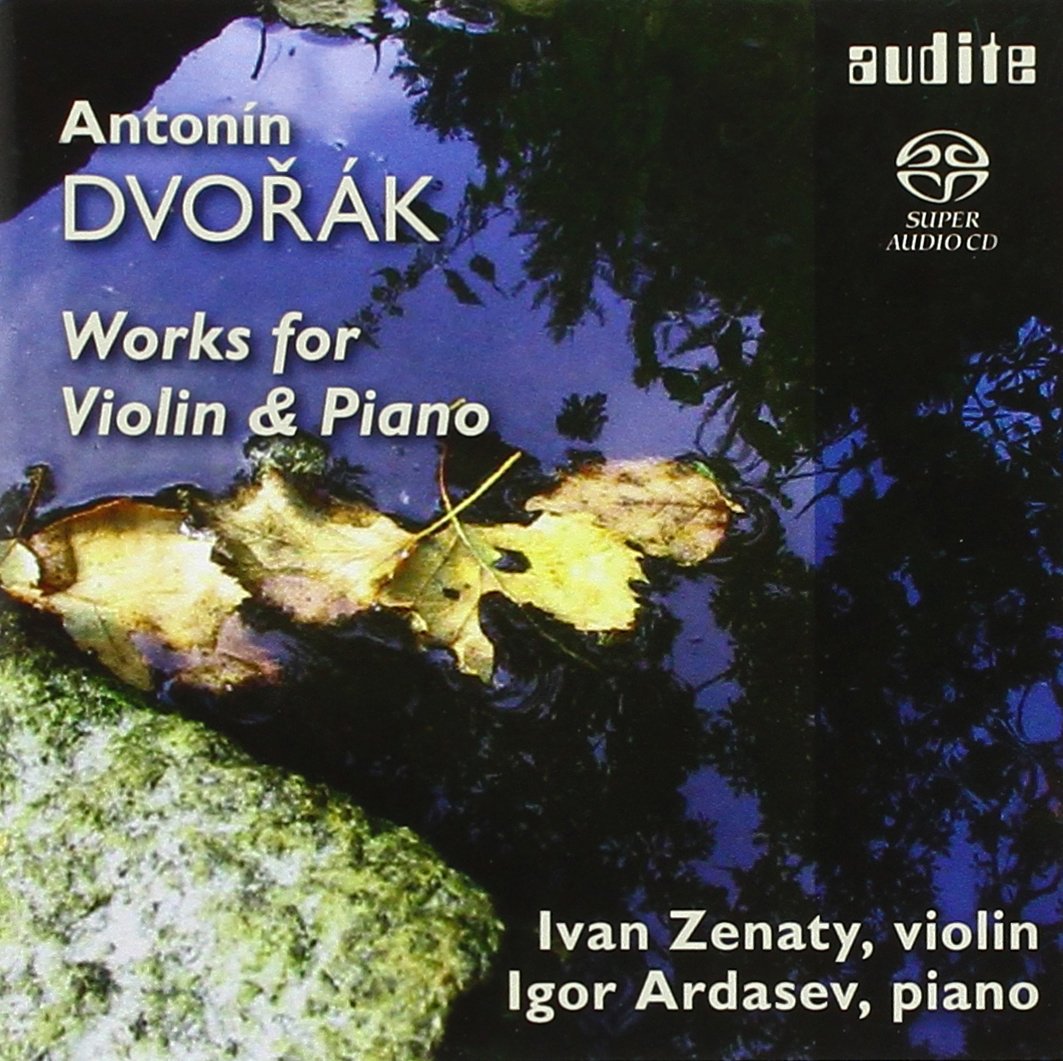

Christian Tetzlaff ingeniously pairs the piece with something unexpected, Giovanni Battista Viotta's Violin Concerto No. 22, from the end of the 18th century. It is a piece that Brahms and Joachim both loved. Tetzlaff notes in his booklet comments that Brahms used it as a model for the Double Concerto, including the choice of key (A minor) and some motifs that are borrowed. Brahms wrote to Clara Schumann of the Viotti concerto as one of his "very special raptures," and by including it in the Double Concerto, it is a way to recall to Joachim one aspect of their early friendship through this music. The first movement may not much to speak of, other than some showy bits in the solo part, but the second movement is quite gorgeous, in addition to its significance in relation to the Brahms. The younger Tetzlaff gets her solo piece as well, an encore-like lagniappe of Dvořák's "Silent Woods," an Adagio arranged for cello and orchestra from From the Bohemian Forest.

Follow me on Threads (@ionarts_dc)

for more classical music and opera news