Critic’s Notebook: Budapest Festival Orchestra's Brahms Festival in Vienna

Also reviewed for Die Presse: Iván Fischers Budapester Brahms begeistert im Konzerthaus

J.Brahms, The Symphonies Fischer Iván / BFO Channel Classics |

J.Brahms, The Symphonies G¨nter Wand / NDRSO RCA |

J.Brahms, The Hungarian Dances Fischer Iván / BFO Philips |

The Delight of Sheer Craftsmanship

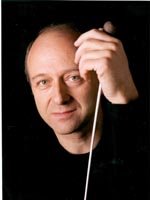

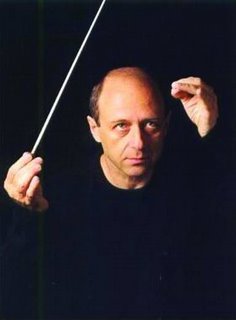

The Budapest Festival Orchestra has a little Brahms Festival going on at the Konzerthaus in Vienna, where they play(ed) all four Symphonies, the major concertos, and a little stuffing and garnish around it all. On this, the third of four concerts last Thursday, they presented the Third Symphony and the Violin Concerto, embedded in two Hungarian Dances. It was a triumph of craftsmanship over showmanship.

In their unassuming way, the two Hungarian Dances, Nos. 17 (orchestrated by Dvořák) and 3 (by Brahms himself), almost stole the show. Relaxed and matter-of-factly on the outside, but lovingly painted in with all the Echt-faux Hungarian/Gypsy vibe, that Brahms so lovingly imbued it with. The orchestra produced that color in spades, with real fiddling, twirping, cooing, lively and colorful, and with lots of transparency amid the large orchestral apparatus. The third Dance wasn’t so much played, it was downright danced – all with a coy, knowing little smile around the orchestra’s collective lips.

Then there was Nikolaj Szeps-Znaider (he’s not going the full Stephen Bishop-Kovacevic on us, he’s merely restored his full last name to his artist’s biography, having felt bad dropping the first part out of career-considerations many years ago). Happily, he was playing the violin, not conducting. He played along with the tuttis before his entry – and when it came, it was as if notes simply poured forth from his instrument, in a nice, leathery tone. Fischer and Znaider both went for a nicely unsentimental, none-too-sweet tone yet for plenty romantic freedom: Flexible phrasing, liberal portamenti, all building on the dark sound of the orchestra. More buoyant than energetic, more flexible than suspenseful. Even the oboe, gifted the finest melody of the work, didn’t indulge and went for clear lyricism instead of schmaltz. After the imposing first movement, a part of the Viennese audience applauded. Shocking, I know. More shocking still: This was the third time this week this happened (all after movements that clearly demand applause, that is), and already the second time that the Vigilant Applause Police™ did not hiss them down. Might things be changing for the better?

In the rhythmically tricky Third Symphony of Brahms, the Orchestra under Fischer Iván showed full command over the score. Without much of a fuss, they started in the Allegro con brio. The shifted pulse, that the second violins answer the first violins with, came to the fore beautifully – helped by the antiphonal seating, with the violins facing each other on either side of the orchestra. The double basses were happily plucking away amid the swinging rhythm or, when called upon, drove their colleagues on with furious strokes. Everything worked like clockwork, everything was solidly put together. There was no show, no smoke and mirrors. No radical tempi, no aggressively accentuated subsidiary melodic lines… but when a brass chorale entered, it did so on point, nicely blended in, and in nearly Wagnerian splendor. The fourth movement, before it comes to its relatively quiet close, built up such force, that the experience became a visceral, physical one – almost oppressively so. Finally a choral encore, as Fischer likes to do: A Brahms serenade (Abendständchen op.42/1) from the entire orchestra-as-amateur-choir. A lovely gesture about making music together – and touching, to boot.

Follow @ClassicalCritic