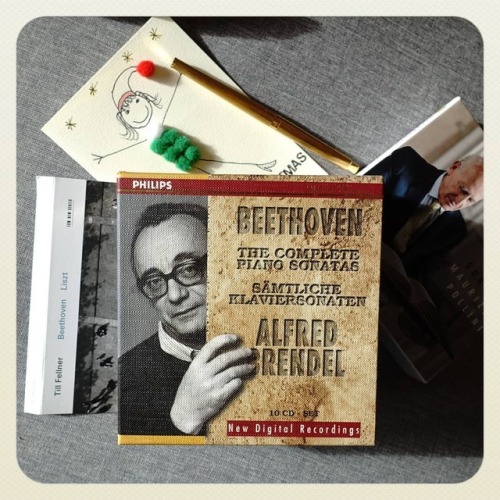

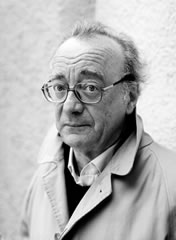

Alfred Brendel is as big a superstar as you’ll find in the world of classical music. The well-filled Kennedy Center Concert Hall was teeming with the highest expectations from a pianist who has, for half a century, represented the highest form of musical craftsmanship in the classical repertoire (well confined on record; more diverse in recitals, to Beethoven, Mozart, Schubert, and Haydn). The term “craftsmanship” is deliberately chosen: Brendel has attained his fame solely through the quality and consistency of his performances, not through flashy appearances or particularly dazzling playing. He does not impress with sheer brilliance (as might Maurizio Pollini) or through eccentricity (as did Gould, Michelangeli or Cziffra) or immediately appealing soft and seductive touch (such as is Mitsuko Uchida’s). He is more likely to endear piano music lovers with his musical faculties, impeccable judgement; subtly extracting more sense from a sonata, a movement, a phrase, than most of the (technically more endowed) colleagues half or one third his age ever could. Given the extraordinary expectations and this particular style of playing, some listeners may leave a Brendel recital a bit underwhelmed (though hardly disappointed). But knowing what one is in for – and even just getting a hint of the depth of his interpretation, the intellectual and emotional grasp he has on the presented works, Brendel will amaze. And do so as is his style: unassuming, subtly.

Alfred Brendel is as big a superstar as you’ll find in the world of classical music. The well-filled Kennedy Center Concert Hall was teeming with the highest expectations from a pianist who has, for half a century, represented the highest form of musical craftsmanship in the classical repertoire (well confined on record; more diverse in recitals, to Beethoven, Mozart, Schubert, and Haydn). The term “craftsmanship” is deliberately chosen: Brendel has attained his fame solely through the quality and consistency of his performances, not through flashy appearances or particularly dazzling playing. He does not impress with sheer brilliance (as might Maurizio Pollini) or through eccentricity (as did Gould, Michelangeli or Cziffra) or immediately appealing soft and seductive touch (such as is Mitsuko Uchida’s). He is more likely to endear piano music lovers with his musical faculties, impeccable judgement; subtly extracting more sense from a sonata, a movement, a phrase, than most of the (technically more endowed) colleagues half or one third his age ever could. Given the extraordinary expectations and this particular style of playing, some listeners may leave a Brendel recital a bit underwhelmed (though hardly disappointed). But knowing what one is in for – and even just getting a hint of the depth of his interpretation, the intellectual and emotional grasp he has on the presented works, Brendel will amaze. And do so as is his style: unassuming, subtly.

The Haydn sonata in D major, Hob. XVI:42 (no. 56), that opened the recital, a speciality of his and much appreciated in a town that is a comparative Haydn wasteland, exemplified that all too well. Schubert’s G major sonata, D894, is a different beast than the witty Haydn. Assertive and yet mildly sung its opening, Austrian lilt in every phrase: Brendel was able to string the music into a gripping narrative, a story that had you on the edge of your seat, hungrily soaking up every word from the master storyteller who read it to his audience with passion and authority, softly here, dominant there, compelling at every moment. If there had been worry that he might fail to impress, it was eradicated at this moment, at the latest.

The Haydn sonata in D major, Hob. XVI:42 (no. 56), that opened the recital, a speciality of his and much appreciated in a town that is a comparative Haydn wasteland, exemplified that all too well. Schubert’s G major sonata, D894, is a different beast than the witty Haydn. Assertive and yet mildly sung its opening, Austrian lilt in every phrase: Brendel was able to string the music into a gripping narrative, a story that had you on the edge of your seat, hungrily soaking up every word from the master storyteller who read it to his audience with passion and authority, softly here, dominant there, compelling at every moment. If there had been worry that he might fail to impress, it was eradicated at this moment, at the latest.

Not infallibility but the humanist touch that every note came with designated the performance as special and inescapably so even as soon as half way through the (admittedly long)

Molto moderato e cantabile of the first movement (played without the repeat). Brendel, in his intimate relation with his Hamburg Steinway, created an atmosphere that would have compelled Beckmesser to drop his chalk and sit with – not amazement… but joyous awe. Between the soft bubbles and the long, energetic steps of the

Andante, this casual piece, mellow despite a wide range of dynamics, made clear that no other sonata (none that I could think of off the top of my head, at any rate) could have better shown a light on the particular strengths of Sir Alfred Brendel’s playing.

Additional Remarks by Charles T. Downey:

Even played without repeats, this Schubert sonata is an example of the "heavenly length" often attributed to this composer's works. Composed in 1826, it is in Schubert's mature style -- well, as much as we can say that about someone who died in his early 30s -- and Brendel handled its four rather different movements with consummate artistry. Schubert had such melodic facility, seemingly able to write nothing more easily than a beautiful tune. If a pianist doesn't have a beautiful touch on the keys, Schubert is not the right music to be playing, and this is one of Brendel's greatest strengths.

Intellectually, Brendel is one of the most perceptive interpreters, too, without bringing any of the aridity one fears from cerebral players. When the first theme of the first movement deceptively returned in the development, in a foreign key, it was so bittersweet, preparing for its triumphal return at the recapitulation. This is possible because Brendel understands form and can back up that understanding with such color and texture in his fingertips. His greatest strength is in soft, delicate, nuanced music, and the Schubert second movement had an astonishing sotto voce ending that was pure Brendel. The fourth movement, with its ricocheting repeated notes, was a marvel, as was the music-box tinkling of the third movement's trio.

It was Mozart that opened the second half, two rather small pieces presented as delightful miniatures. The solemn Fantasia in C Minor, K. 476, is the better-known of the two, played with finesse and intelligent handling of the motivic fragmentation that seems to be Mozart looking forward to Beethoven. However, it was the Rondo in A Minor, K. 511, that most impressed, a work heard much more rarely. It strikes me as a private piece, full of chromatic experimentation, a sort of harmonic notebook that records Mozart's fascination with the counterpoint and extended chromatic harmony found in the works of J. S. Bach.

We could not have asked for a better conclusion than one of Haydn's best comic piano pieces, the Sonata in C Major, Hob. XVI:50, composed during Haydn's trip to London in 1794. Here Brendel showed off his ability to play runs in thirds in his right hand, done not only accurately but with flair. To compensate for the shorter length of the second half, he took all of the repeats, to our delight. By the time that Brendel got to the rondo, after an exquisite slow movement, we were really having fun. The third movement is a textbook example of Haydn's wit, with its chippy theme that sometimes takes one or two false harmonic shifts to get started or conclude. With a twinkle in his eye, Alfred Brendel gave the joke its due, with none of the vulgarity that could come from too heavy of a musical guffaw. Haydn requires only a devilishly raised eyebrow, not a jab of the elbow in our sides.

|

What we get in Brendel is the simultaneously serious and comic, the orderly and the absurd. Little wonder one of his favorite quotes is Novalis’s sentence that “Chaos, in a work of art, should shimmer through the veil of order.” In Brendel on stage you see the veil; in his playing you hear what is going on behind it. The machinations of joyous re-recreation at every turn of a phrase. In the book

Me of All People, a conversation of Brendel with Martin Meyer, he paraphrases Schwitters: “If I had to choose between sense and nonsense, I personally would prefer nonsense… Not in piano playing, where one hopes for performances that do not maltreat masterpieces, but elsewhere.” His admiration of Georg Christoph Lichtenberg and Woody Allen shed further light on the man and performer – inseparable – Brendel. The veil of this old-European, dignified, and serious man (a persona we already don’t believe in anymore, by the time we've heard this much music from him) is finally lifted – quickly, as if for a peak – when Brendel ends a concert, a last piece, an encore. Out of the corner of his eyes comes a puckish glance through which we see the almost child-like joy that he took in offering a sly last chord, an abrupt ending, a musical joke.

Tuesdays could end worse than with Mozart-Mozart-Haydn, courtesy of Alfred Brendel, even if Mozart’s

Fantasia in C minor, K. 475, may not touch quite as profoundly as the preceding Schubert. Then again, the way Brendel carved his turns in the music, combined with some of the wit of Haydn and the trademark sound of (often deceptive) effortlessness, it nearly does. This – as the following Mozart

Rondo (A minor, K. 571) and Haydn sonata (Hob. XVI:50) – is the daily bread of Brendel’s – which is not to say he treats it as Bread & Butter work. In the faster passages over the rumble from the right hand, the ‘old man’ showed that he needn’t retire any time soon, after all. Suddenly his playing was all fleet, his fingers plenty nimble.

Let this be the first warning to the Mozart performer: piano playing, be it ever so faultless, must not be considered sufficient. Mozart's piano works should be for the player a receptacle full of latent musical possibilities which often go far beyond the purely pianistic. It is not the limitations of Mozart's pianoforte (which I refuse to accept) that point the way, but rather Mozart's dynamism, colourfulness, and expressiveness in operatic singing, in the orchestra, in ensembles of all kinds.

A. Brendel - A Mozart Player Gives Himself Advice - Music Sounded Out

Complete mastery was achieved during the Fantasia’s five little movements such that it can keep the young pianist Turks at bay for a good while. Especially since no one has ever succeeded with Mozart on account of technical ability alone; while few can match the (more important) musical spirit that is Brendel’s, the ingenuity of his touch. I, for one, should be happy to leave

Hammerklavier sonatas or

Petrouchka suites to others (a hand injury ruled those works out years ago) and hear similar… heck: identical programs from Brendel until he decides to end one of the most illustrious pianistic careers of our time, an impression the

Rondo only further underscored. Particularly in Mozart, the Brendel of 75 years in flesh and blood outplayed the Brendel of any age on record. His recordings are always good – but nothing that I ever heard of his in Mozart had prepared me for the ease and easily discernable superiority of his playing.

Nothing could have been more head-boppingly delightful than Haydn’s sonata at the end of what was already a great recital. I hope that his Haydn, perhaps in duo with the Concertgebouw’s

Surprise Symphony next Monday, gives that most quintessential Austrian composer a little, more than deserved, boost. His piano sonatas, piano trios, Scottish folksong arrangements, concertos all deserve more attention. Sonata no. 60 was infectious from

Allegro to

Adagio (masterfully as always with Haydn) to

Allegro molto (a silvery brook). Towards the end it was difficult to tell who had more fun – Haydn, Brendel, or the audience. Their enthusiastic response earned them a Mozart encore – the

Andante cantabile con espressione from the A minor sonata, K. 310. An evening after which everyone seemed to glow – Brendel included.