From the 2012 ARD Competition, Day 7

Day 7, String Quartets, Semi Finals

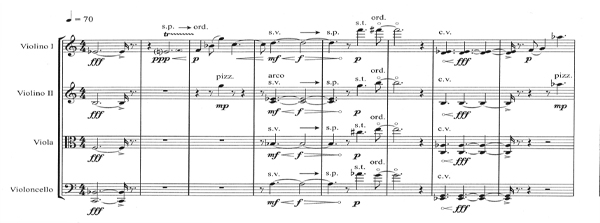

Six string quartets (performers) and 18 string quartets (compositions) in just under nine hours is something you will not likely experience anywhere outside the ARD Music Competition. It’s a marathon, exhausting and gratifying, and particularly insightful when it comes to the ARD commissioned competition that participants of the semi final are required to play.For the String Quartets in 2012, that was a composition by Erkki-Sven Tüür, Lost Prayers—his second string quartet, which is quite easy on the ears, comprehensible, not all too novel, and full of musical references that the ear consecutively grasps after one, two, three hearings. Notably there is a general kinship with Gregorian, or Schütz-like sentiments (not surprising if you know his Wanderer's Evening Song), there are long dramatic arches that emerge, and also hints—but just half a second long—of extreme romanticism. It’s a work that pays homage to the string quartet tradition, and continues it… written expressively for the instruments, not against them. If it’s a little tedious in its constant stymied run-ups that are lost in flageolet notes before the whole shebang starts over again until it finally reaches fruition after the eleventh or so time… well, it’s also a lot better than this commissioned piece could have been. The voices—this year and those from 2009—should know what I mean.

The Acies Quartet (Benjamin Ziervogel & Raphael Kasprian, violins, Manfred Plessl, viola, Thomas Wiesflecker, cello), experienced favorites, were the first to go—which meant the world premiere performance for Lost Prayers. Every hearing of a new work is a learning experience, even with the very readable score on one’s lap, but the Acies’ transparent, nuanced, gently lit account was just about ideal for a first listening. Rather than single-mindedly reciting the text in front of them, they made their own (though perhaps not Tüür’s) musical sense of it, even if that meant not slavishly following every dynamic marking, or lack thereof.

The Novus Quartet (Jae-young Kim & Young-Uk Kim, Violins, Seung-won Lee, Viola, Woong-whee Moon, Cello – from the Korea National University of Arts) went about it differently, informed perhaps by a desperate instinct to get as much sentiment out of the work as it lends itself to—which is a considerable amount: the enthusiastic audience response was telling. Faster, wilder, less differentiated, more pronounced rhythmically, and with untrammeled drive from the forth-to-last section onward… lunging onto the fff marking 29 bars before the end, and not letting go of it. At the expense of some detailed vocal interplay, this was the more effective way to play it, which helped, as did the fact that the audience had already gotten used to the work.

It was the four young French ladies of the Quatuor Zaïde (Charlotte Juillard & Pauline Fritsch, violins, Sarah Chenaf, viola, Juliette Salmona, cello) that came up with the very nearly ideal hybrid of those two approaches. The outer form, the tempos, and the willingness to play up the effects were very similar to the Novus Quartet’s performance, but with most—not all—the discriminate, meticulous inner workings of the Acies Quartet. Their dynamic range was the widest; their ppp-s quite good, their fff-s riveting; ditto their expressive range from aggressive to filigreed.

The takes on Schubert’s Quartetsatz (performed by all three quartets in this first batch of the day) and Mozart (a different quartet from each of the six groups in the semi final) were more similar, but hardly identical. The Acies Quartet established a real chamber-music feel, intimate and casual, with their Schubert (wispy-blistering entry, coolly floating along and then outbreaks with force that appeared ever more sudden given their unforced surroundings) and with Mozart’s d-minor Quartet K421. It was especially in the latter as if they had nothing to prove. The Acies’ ensemble work is air-tight anyway, and their interpretation was near-minimalist, without bells and whistles.

Schubert(+ Beethoven, Haydn), Quartettsatz et al., Acies Quartet Gramola     |

Quite different the Novus Quartet in Mozart’s E-flat quartet, K428. After a deconstructed opening that was bewildering even after just hearing the Tüür, they went about their job with blazing speeds, infused Mozart with an (unintentional?) modernity, a kind of momentum and non-celebration that this biased mind found un-Mozartean certainly, and unsuitable. At first. But really it was an intriguing take, and a welcome one. Theirs is, after all, not a performance to suggest how Mozart ought to be played, only the way they chose to play it at that moment. The Menuetto & Trio was not romantic per se, but treated with the interpretive tools one would use on Bartók. The Allegro vivace was full of hyper-accentuation, and a bit of a race, but it’s what works with the audience, and it’s possibly what worked for the jury (apart from a said-to-be fantastic Lyric Suite from Berg in the second round), too. In any case, they went on to the finals.

Their Schubert, for all the superficial emotive gestures, had an underlying pulse that was steady as it was pleasantly propulsive. They have good (certainly ‘big’) sounding instruments and tend to play in an instrument-reliant way, of which the Schubert was a good example.

Quatuor Zaïde played the Schubert for effect—with little electro-shock-therapy accentuations, not unlike the Novus Quartet but less based on sound. The quartet’s viola has a tendency to get lost, not the least because she sits right next to a boom-box of a cello. Said cello was particularly lovely in the Mozart, although it distracted just a little that the gal steering it would stare, as if a transfigured sheep in deep space, into the greater nothingness above… as if that made those lovely notes she played yet more lovely, or her tasteful vibrato any more sensual. The music of Mozart’s difficult quartet in F, K590, the last of the “Prussian” quartets, was lightly touched in the finale of the first movement, and spoke for itself. The Andante was beautifully balanced and naturally heartrending, without additives… the Menuetto slight, without side-effects, and the Allegro Finale played like Beethoven channeled through Mozart. All in all a most pleasing set of performances, and their ticket to the Finals.

The Calidore String Quartet (Jeffrey Myers & Ryan Meehan, violins, Jeremy Berry, viola, Estelle Choi, cello). performed Mozart’s “Dissonance” Quartet in C, K465. What was Mozart thinking when he composed that? No matter how much I know the dissonant-seeming opening and expect it, I can’t help but marvel at it and wonder why it would remain such a singular teaser of ‘shifted consonance’—an extreme, written-out Über-rubato, if you will—in the composer’s œvre. It’s the ideal piece of music to use as an introduction to why Alban Berg’s music is decidedly romantic.

W.A.Mozart, K421, 465 & 138, Quatuor Ébène Virgin     |

Their Tüür was nicely articulated, even as—a problem with most quartets—the dynamic markings (pp to mp) were condensed to more or less one sound. That one lush ray of romanticism at bars 89/90 was declined by not adding a little indulgent (in any case not indicated) pause. The cackling ricochets were less pronounced than with previous quartets, and the overtone glissandi almost inaudible. Schubert’s Quartettsatz finally was performed almost as if in anger, with abrupt tones, not stringently, and with plenty merit.

* The name being a conglomerate of “California” and “D’Or” or (apparently) “doré”, the gold-silver alloy, perhaps with a hidden hint to their Canadian-American blend… but not pronounced “Calidoré”.

When the Quartet Berlin Tokyo (Tsuyoshi Moriya & Moti Pavlov, violins, Eri Sugita, viola, and Ruiko Matsumoto, cello) performed the Tüür, low lyrical notes dominated the pointed, dotted glissandi’s above, and it had a superb pulse audible from “P” onward— rhythmic much like a Peter Gabriel song that escapes me just now—with which they grooved all the way to the finale.

A.Webern, Works for String Quartet, Artis Quartet Nimbus     |

It was the cello-biased Quartet in D, K575 that they chose from among Mozart’s quartets, and it was a very curious, aimless sort of way in which they noodled through the introduction. But it was also soon lively and playful, with a slow movement full of requisite loveliness, despite the flat cello notes. The Menuetto wasn’t played as a throwaway, thankfully, but I could have done without the repeats, every last one of which was taken—not just by these players but by every quartet in the semi-finals. The Allegretto, finally, was dance-like, a happy notion, hardly imperious but very lovely.

The Armida Quartet (Martin Funda & Johanna Staemmler, violins, Teresa Schwamm, viola, Peter-Philipp Staemmler, cello) was last to go—some eight hours after the day of string quartets had begun. Tired and over-musicked, I noticed my attention sag and my charity wane. I still appreciated much of what was lovely about their Webern and their Mozart and their Tüür (for which they would end up receiving the best interpretation’s Prize, which also met the composer’s approval). Their Webern, though swift (which at this point appreciated on many levels), I found bested by Berlin-Tokyo in that the latter players sparked a greater variety of images in my mind—except for a very musical V, “In zarter Bewegung”.

In Mozart I quibbled with an uneventful B-flat Quartet, K589, which sounded a little pale and well-behaved—a little like the Acies, minus the raw performance quality but with a lighter, much more dynamic texture and their one particular sound. The Acies in the morning I had given the benefit of the doubt that they daringly wanted to let the composer speak for himself… Here I felt, perhaps unjustly, a little bored—and increasingly enervated by their dynamic gestures which I found heavy handed and predictable and often ungainly, in their forced, grinding ways. A bit like a down-hill skier who takes every corner with extra-extra swerve instead of lightly working his way ‘round his or her turns. A minority opinion by all accounts: They, alongside the Novus, Zaïde, and Calidore quartets made it into the finals and as favorites, to boot.