Master of the Magdalen Legend, Virgin and Child, 1490/1500, and unknown French artist, Willem van Bibaut, 1523, Private Collection |

Right at the entrance are two tiny wonders, paired Annunciation panels of Gabriel and the Virgin Mary, by Jan van Eyck, now in the Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza in Madrid. For their illusionism, they are reminiscent of similar trompe-l'œil painting in the Ghent altarpiece, a style that van Eyck learned painting manuscript illuminations. The two figures facing one another look like diminutive marble sculptures standing on pedestals, their reflections refracted on shiny obsidian slabs on the wall behind them: it is all paint. It is one thing to see this on a slide in a classroom or via the Internet, but in person the experience defies description.

Paul Richard, Medieval Meets Modern (Washington Post, November 13) Joanna Shaw-Eagle, Powerful Christ images overwhelm in pairs (Washington Times, November 25) Menachem Weckler, Donor Saints (DCist, November 28) Holland Carter, Divine and Devotee Meet Across Hinges (New York Times, December 15) |

Of the latter there are several striking examples, including the Virgin and Child diptych Rogier van der Weyden made for Philippe de Croÿ. (These panels are happily reunited for this exhibit: normally the left panel resides in the Huntington Library and the right in the Koninklijk Museum voor Schone Kunsten in Antwerp.) Although the artists did everything they could to connect the two panels -- to make clear that portrait and icon were set in the same location -- the gaze of the portrait subject often does not rest on the object of devotion but peers out beyond it. Philippe de Croÿ, a young Burgundian courtier, seems to stare glassily right through the Virgin and Child.

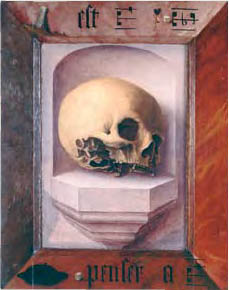

Jan Provoost, Skull in a Niche, recto of 54-Year-Old Franciscan, 1522, Sint-Janshospitaal, Bruges |

Equally appreciated in this exhibit is the opportunity to walk around most of the pieces, to observe both front and back. On the back of Jan Provoost's Christ Carrying the Cross panel is an unsolved rebus around a frightening memento mori skull in a niche. (Of course, I had to spend some time trying to figure out what the puzzle means, but I'm not there yet. Try it out yourself above.) In the later rooms, we see the diptych being transformed into a more traditional family portrait, without the devotional part. The most interesting work in that section of the exhibit is the Quentin Massys diptych, which combines a portrait of Desiderius Erasmus with that of his friend Peter Gillis. It turns out that these panels were made as a gift to bestow on a fellow humanist visiting the Netherlands from England, one Thomas More. Once again, this pair now lives separately, one at the Palazzo Barberini in Rome and the other in Antwerp.

Prayers and Portraits: Unfolding the Netherlandish Diptych, at the National Gallery of Art, will be open to the public through February 4, 2007.

No comments:

Post a Comment