Sophie’s Choice

Sophie’s Choice, first a book by William Styron, then a film with Meryl Streep and Kevin Kline, is now an opera… and a

most welcome

American premiere by the Washington National Opera, which is taking a fair amount of risk whenever it mounts productions of challenging and modern work.

Fortunately Nicholas Maw is a fairly well-known and much-liked composer (and neighbor) here in the Washington region;

Sophie’s Choice a well-known – though perhaps too disturbing to say: popular –

sujet and the cost of the new production defrayed by the partnership with the Berlin and Vienna opera houses that staged it before Washington did. It premiered at Covent Garden under Simon Rattle in a Trevor Nunn staging in late 2002 to rather mixed reviews.

Other Reviews, Washington Production:

Tim Page, A Searing 'Sophie's Choice' (Washington Post, September 23)

Tim Smith, Affecting premiere of 'Sophie's Choice' (Baltimore Sun, September 23)

T. L. Ponick, A 'Choice' not for the faint of heart (Washington Times, September 23)

Justin Davidson, Being noble may not be 'Sophie's' best choice (Newsday, September 25)

Charles T. Downey, Nicholas Maw's Choice (DCist, September 26)

Other Reviews, Covent Garden Production

Anna Picard, Guilt, genocide, madness, masochism, sexual obsession ... and schlock (The Independent, December 15, 2002)

Tim Ashley, Sophie's Choice' (The Guardian, December 9, 2002)

Alex Ross, Opera As History (The New Yorker via "The Rest is Noise", January 6, 2003) |

The reaction to the Washington National Opera’s performance will not be much different. Maw’s music throws few bones to the very conservative listener and fewer bones still to the unrepentant modernism-loving listener. It occupies a realm that is hard to define – not exactly neo-Romantic but certainly not abstract. An unkind soul might suggest that a lot of it sounds like a collection of scraps from Benjamin Britten’s cutting room floor. If that sounds too unkind, add to it that most of

Sophie’s Choice is high-quality work with a good story that, despite minor misgivings, works very well in the theater (less so of you know the film or the book – which is why I won’t spoil the story for the lucky ones who don’t know what Sophie’s “choice” is) and captivates. Wonderful singers, a clever, resourceful staging, much good music combine for an opera that one very much

wants to like. But it’s not so easy.

Anyone who has seen or will see

Sophie’s Choice will be utterly thankful to the

über-competent Marin Alsop (the WNO orchestra played like a well-oiled machine under her leadership) who went ahead and cut a bit over an hour from the original opera. Even without having seen it, I instinctively greeted the news with “probably for the better” and “thank God.” Little did I know that these cuts brought the opera down to ‘l-o-n-g’ from what would otherwise have been ‘near unbearable’.

(Curious that we should appreciate a conductor’s incisions of contemporary work with preemptive laud – but are going through a phase where we feign outrage if a record company might serve us anything less than the ‘complete-complete’

Hippolyte et Aricie or

La Didone or even

Die Frau ohne Schatten or

Rienzi. All works that no sane music director would have tried to shove down his clientele’s throats uncut. Perhaps our earnestness about

Werktreue combined with the completists’ urge works against an otherwise more lighthearted enjoyment of classical works?)

Unless you simply don’t like modern opera without recognizable tunes and arias (starting with Wagner, really – although I am mostly thinking

Peter Grimes and

Billy Budd), it’s not so easy to put your finger on what’s missing in

Sophie’s Choice that makes the whole a good deal less than the sum of its parts. Is it the libretto (Nicholas Maw himself) that seems to try too hard at times, with forced joviality and forced seriousness? I prefer to ascribe the most outrageously clunky phrases to the characters and not the librettist’s lack of subtlety. Sophie’s “I am the avatar of menteuses” for example is a quote from the book… though meaningless without the context the book gives. A ‘showtune’ scene (replete with spotlight) that ends up praising nothing more than the importance of iron in a good diet (try calf liver, leeks, and creamed spinach) and adds “a plain little salad”, is cute if we think of it as poking fun at itself and ‘all-too-serious’ opera. Even, I suppose, an opera that has the Holocaust at its much unspoken-about center.

I don’t think the problem lies in the story, now smacking of a ‘domestic abuse’ drama between Nathan and Sophie (but neutered of Stingo’s – their roommate and the opera’s narrator – very sexual interest in Sophie), instead of delicately unraveling the complex character of Nathan. Nor are the moments where the dramatic development comes to a crashing halt anything more than unfortunate. When the old, narrating Stingo tells of Sophie’s confession about the true nature of her father, his rhetorical questions (“Was her father

really such a good guy?”) are highly unnecessary – hence ‘rhetorical’ – since we are shown that he obviously wasn’t, anyway.

The main problem I see with

Sophie’s Choice is its relentlessness: there is so much story that needs to be told in this opera that there isn’t a moment where the push to tell it can rest. The music is relentless in its often beautiful but hard-working assault on our senses. The characters’ vocal characterizations are persistently similar to each other, the style of singing unyielding and a permanent stentorian push. There is scarcely a moment that the characters can let their voice sail on… even the smallest phrase becomes vocally demanding. And despite the very mindful, voice-friendly conducting of Marin Alsop, this constant pushing had as a result that especially Rod Gilfry (Nathan Landau) and Dale Duesing (Narrator / old Stingo) sounded very strained by the second performance already, with a good number of – admittedly small – cracks here and there. Problems that apparently did not exist on opening night – nor, for that matter, during the final rehearsal.

The music, too, is unrelenting. It offers too few notable contrasts, too little in variation. In short, it’s far too monotonous. The orchestral score, rich and varied in itself, cannot assert itself against the singers and stays curiously muted for most of the opera. Listening to

Lulu – in many ways a more modern opera – for contrast makes clear that

Lulu has moments that dance, moments that radiate, shocking beauty, recessed elements, whirls gaily about.

Sophie’s Choice drives and drives the same – generous – music on and on. It’s like an organ grinder fed his machine with

Albert Herring and grinds away without mercy. Only with Nathan’s recital of an Emily Dickinson poem comes a break with very different music – in this case an extraordinarily beautiful lyric it. Not even the “Iron-Showtime-Song” varies from the rest. Charles Downey may have repeated in his review the point he made to me: “The opera comes across as three hours of modern recitative”. A violin solo at the end, an English horn solo a little before that, the orchestral postlude all hint at how this music – tonal but not always comfortably so – can hide warmth and greatness… but it’s too little spread over too much.

The above does admittedly not read like a glowing endorsement. I cannot leave it at that.

Sophie’s Choice is an opera that I not only want to like, it is a drama that I was very glad to have experienced. I was, for all the distractions or the gritty procession of the story, captivated by what was unfolding on stage and moved, if not downright shocked, at the dramatic climax, even the second time I saw it.

Sophie’s Choice is an opera that will grip the audience sufficiently to merit being seen by anyone who does not mind theater on stage with the lines all sung. At just over three hours it is now of a very reasonable length (although the second time around the third and fourth acts became longer and longer as they went on) and can be handled even by those who may not like the music but are interested in the drama. The staging and direction (Robert Schweer and Markus Bothe, respectively) ensure that the imagination of the viewer automatically fills everything in that they don’t prescribe. It works extraordinarily well and goes a long way in accentuating what is good about this opera, hiding some of its weaknesses.

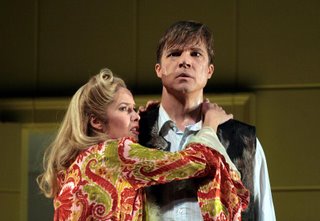

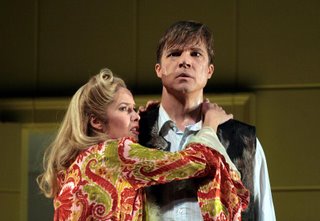

Finally, the singing (and acting), with the above-mentioned caveat, is extraordinarily good. Angelika Kirchschlager – an ever-popular Cherubino or Octavian – is rarely heard in music like this, her characterization (including her accent) superb. Gordon Gietz may seem unimposing next to Rod Gilfry but sang without any sign of weakness throughout the opera and impressed thoroughly. Dale Duesing was a little pale on Sunday while Gilfry’s odd moments hardly distracted from a more-than-solid vocal- and excellent dramatic performance. These four singers all created and premiered their characters. From the supporting cast it was Corey Evan Rotz (a happy

Froh in

last season’s Rheingold) who made for an excellent concentration camp

Kommandant, Rudolph Franz Höss, and once again proved that he

is much more than just “a convenient patch for an unfilled role” at the WNO.

Sophie's Choice is so welcome a premiere at the WNO, not because it is an unalloyed success (it isn't) - but because without companies staging contemporary works, opera would no longer be a living art form. And if modern works do not get a fair share of repeat performances, they could never enter the repertory. Even if not every production or work is a winner itself,

Opera as such - and the company performing it - is a winner. The

next performance takes place tomorrow, Wednesday, September 27th. The performance on September 30th will be the last one with Rod Gilfry as Nathan Landau: Scott Hendricks will take over for the remaining two on October 5th and 9th.

HIRSHHORN MUSEUM OF ART:

HIRSHHORN MUSEUM OF ART: