Ionarts in Santa Fe: Salome

And so ends another year for Ionarts at Santa Fe Opera, with Richard Strauss's Salome (1905), a work that along with Debussy's Pelléas et Mélisande (1902) set the tone for opera in the 20th century. Both adapted famous works of literature from the late 19th century, made famous by their controversial style and content. Opera as a genre would never be the same. Strauss was one of SFO Founder John Crosby's favorite composers, and over the course of its 50-year history, Santa Fe Opera has mounted 13 of his 15 operas (only Guntram and Die Frau ohne Schatten are on the To Do List), five of them for the first time ever in the United States.

Janice Watson with Jokanaan's head, Salome, Santa Fe Opera, photo by Ken Howard © 2006 |

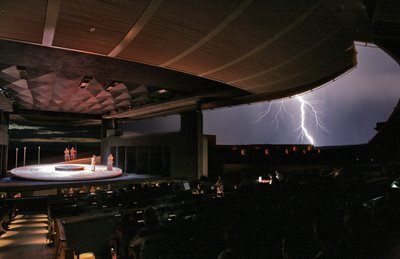

Salome, Santa Fe Opera, with natural lighting, photo by Ken Howard © 2006 |

Although there is little to suggest the decadence of this court and the incestuous depravity of this family, the score and libretto communicate it still quite forcefully. Perhaps the shocking indecency of the story would be more acidic, less likely to provoke laughter, if it were updated to, say, the setting of Desperate Housewives. A brazen teenage Britney Spears takes advantage of her lecherous and wealthy stepfather's lust for her to have a holy man put to death, only to kiss his decapitated head. On second thought, that is a terrible idea. The story is grotesque enough just as it is.

Janice Watson as Salome and Greer Grimsley as Jokanaan, Salome, Santa Fe Opera, with natural lighting, photo by Ken Howard © 2006 |

Tenor Ragnar Ulfung has been a regular at Santa Fe Opera for 40 years, and casting him as Herod this year was a touching tribute to a man who first sang the role in Santa Fe in 1967. (You are mostly likely to have seen Ulfung as Monostatos in Ingmar Bergman's unforgettable film version of The Magic Flute.) That's a lot of water under the bridge, and it is hardly a surprise that his performance was often more like Sprechstimme than a Straussian role, imprecise and strained. English mezzo-soprano Anne-Marie Owens, reprising the role of Herodias from the 1998 Santa Fe production, was a potent, shrewish wife. The supporting cast was good, with particularly fine performances from tenor Dimitri Pittas as Narraboth and Andrea Silvestrelli (also Sarastro in this summer's Magic Flute) as the Cappadocian. Conductor John Fiore led the orchestra in a full-throated performance, surely not the full 105-instrument orchestration that Strauss originally penned. All the powerful sounds were there, including those thrilling trumpet statements of Jokanaan's dominating theme and the solo cello's cricket chirping as Salome listens to the silent execution and waits for the Baptist's head.

I am thrilled that Strauss appears to be back in Santa Fe, with the company's fourth mounting of Daphne on the calendar for next summer. I hope to hear a lot more Strauss over the next 50 years at Santa Fe Opera.

4 comments:

This from recent reading of "Fortissimo": It seems that the more violent or horrible the subject matter, the easier it is for an opera production to teeter into unintended comedy if something about the production doesn't work. (Author Murray cited Tosca and Il Trovatore as operas that most often fall victim to this effect.) I can picture those moments in Salome when some of the audience responded with laughter, but, you're right, this opera still has the power to shock without any updating. In Baltimore's recent production, most of those moments were enacted in darkness with Salome vaguely discernible on stage. The audience was dead silent, and I couldn't believe what I was witnessing on an opera stage (my first time ever experiencing this opera). The shock expressed by Herod's character provided a parallel reaction on stage that we could identify with.

Old Herods are often criticized for wobbling and cracking their way through the score - often singing as Wagner would have been sung some 70 years ago. Alas, the reason they are cast so - seemingly often - must be, that directors appreciate the kind of characterization it gives to Herod. Most notable among these examples might be the appearance of Hiestermann in the Sinopoli Salome.

Where others criticize the obvious lack of melodic line, accuracy, beauty, I think that - especially from German speaking performer to German-understanding audience member, that kind of choice can be far superior than casting even a top "singer" in the role. Few characters are so decrepit as is Herod – whose inherent weakness makes him the subject of pity but also disgust; more so, perhaps, than the stronger, scheming women around him. To portray the lecherous, pathetic Herod weasling around with his tail between his legs, afraid to shake it before his wife (but winking it at his step daughter, as it were) with that kind of an ugly, insecure voice, can much benefit the presentation of the opera.

Of course there is no telling for me, from a thousand miles away, if that was the case here… but it might offer an explanation why those who cast Mr. Ulfung felt very comfortable with him, even if/especially because his instrument has deteriorated.

jfl

Jens, you may be right. He is also an audience favorite in Santa Fe, which doesn't hurt.

teddybear, thanks for that. I knew I should have checked the score instead of just going by sound.

Post a Comment