Pierre Bonnard in Paris

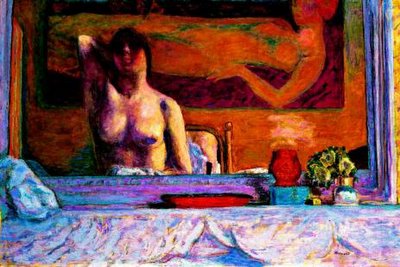

While visiting the Musée d'Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris last Wednesday, I spent some time in the absolutely spectacular Pierre Bonnard exhibit, Pierre Bonnard: L’oeuvre d’art, un arrêt du temps. (For some quotes from French reviews of this important retrospective, see Le Musée d'art moderne de la ville de Paris, February 8.) Bonnard hardly needs any help getting people to like his paintings, but if someone still needs convincing, this is the place for it to happen. In his admiration for the female body, Bonnard is the heir of Ingres, but without all of the academic baggage. You know Bonnard's portraits, his landscapes, his warm, glowing interior scenes, but there are minor works in the show, too, that bring some illumination to a remarkable career, as well as piles and piles of beautiful paintings.

While visiting the Musée d'Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris last Wednesday, I spent some time in the absolutely spectacular Pierre Bonnard exhibit, Pierre Bonnard: L’oeuvre d’art, un arrêt du temps. (For some quotes from French reviews of this important retrospective, see Le Musée d'art moderne de la ville de Paris, February 8.) Bonnard hardly needs any help getting people to like his paintings, but if someone still needs convincing, this is the place for it to happen. In his admiration for the female body, Bonnard is the heir of Ingres, but without all of the academic baggage. You know Bonnard's portraits, his landscapes, his warm, glowing interior scenes, but there are minor works in the show, too, that bring some illumination to a remarkable career, as well as piles and piles of beautiful paintings.

| Available from Amazon: Arthur Gold and Robert Fizdale, Misia: The Life of Misia Sert |

In 1893, Bonnard met his muse, a 16-year-old girl named Marthe de Méligny (née Maria Boursin). Although they were not married for another 30 years or so, she was Bonnard's constant companion and lover, and he obsessively depicted her nude for his whole life. Bonnard showed himself and Marthe, just after sex, in the shockingly intimate L'homme et la femme (Musée d'Orsay, 1900), shown above with the opening paragraph. The erotic portraits of the first decade of their relationship include the naughty L'indolence (private collection, 1899) -- in which Marthe's pose was perhaps inspired by Courbet's infamous L'origine du monde -- and the tender La sieste (National Gallery of Victoria, 1900). This was also the period of Bonnard's fetish for Marthe in black stockings (in several drawings and paintings in the show).

Somewhere around the time of Le Cabinet de toilette au canapé rose (Musées royaux des Beaux-Arts de Belgique, Brussels, 1908) -- a loving portrait of Marthe applying her perfume, shown above -- Bonnard's palette began to lighten toward the lighter, brighter colors we associate with his mature style. By the time we reach the extraordinary Nu au gant bleu (private collection, 1916) and La Cheminée (private collection, 1916), the colors are much more vibrant, leaning toward pastel. This is more or less the classic Bonnard, painting in a positively retrogressive way in the era of Dada and Surrealism. One of the many revelations of the show is the wall of tiny photographic proofs that are snapshots of Bonnard and Marthe, standing nude in their garden. Bonnard cannot be accused of idealizing too much: she was a shapely, thin, altogether lovely woman. There are also several of his pencil drawings and water colors on the opposite wall, revealing somewhat his conceptual process.

Somewhere around the time of Le Cabinet de toilette au canapé rose (Musées royaux des Beaux-Arts de Belgique, Brussels, 1908) -- a loving portrait of Marthe applying her perfume, shown above -- Bonnard's palette began to lighten toward the lighter, brighter colors we associate with his mature style. By the time we reach the extraordinary Nu au gant bleu (private collection, 1916) and La Cheminée (private collection, 1916), the colors are much more vibrant, leaning toward pastel. This is more or less the classic Bonnard, painting in a positively retrogressive way in the era of Dada and Surrealism. One of the many revelations of the show is the wall of tiny photographic proofs that are snapshots of Bonnard and Marthe, standing nude in their garden. Bonnard cannot be accused of idealizing too much: she was a shapely, thin, altogether lovely woman. There are also several of his pencil drawings and water colors on the opposite wall, revealing somewhat his conceptual process.There are rooms, literally, of various views of Marthe lying in or about to get into the bathtub. Perhaps too many examples, although the variations in color and composition from frame to frame are of mild interest. The best example is Effet de glace from the Winterthur Museum, in which Marthe hovering over her bath is reflected in the mirror of a mantel.

There is a similar excess of riches in the number of landscapes, but one cannot argue with the examples selected. Be careful not to miss the three enormous panels of La Mediterranée (1911, Hermitage), made in Russia for a patron's home. They are hung outside the entrance to the exhibit, a little off to the side. Again, there is an entire room of Norman landscapes, toward the end of the exhibit. The domestic views -- part interior and part landscape -- are the best ones, such as the many paintings done at Ma Roulotte, the home in Normandy that Bonnard purchased in 1912. In this category are great paintings like La salle à manger, Vernon (1925-27), very similar to the one owned by the Met.

There is a similar excess of riches in the number of landscapes, but one cannot argue with the examples selected. Be careful not to miss the three enormous panels of La Mediterranée (1911, Hermitage), made in Russia for a patron's home. They are hung outside the entrance to the exhibit, a little off to the side. Again, there is an entire room of Norman landscapes, toward the end of the exhibit. The domestic views -- part interior and part landscape -- are the best ones, such as the many paintings done at Ma Roulotte, the home in Normandy that Bonnard purchased in 1912. In this category are great paintings like La salle à manger, Vernon (1925-27), very similar to the one owned by the Met.Pierre Bonnard: Observing Nature (National Gallery of Australia) Pierre Bonnard Images (Olga's Gallery) Bonnard (1998 exhibit, Museum of Modern Art) Pierre Bonnard: Sous la lumière du Cannet (2001 exhibit, Espace Bonnard, Le Cannet) |

One of the best sections of the show is a hallway with eight of Bonnard's self-portraits, from 1899 to very near the time of his death, with half of them coming from private collections and therefore mostly inaccessible. There we see the precise, reserved, silhouette of a man who did not allow either devastating world war in Europe to have any perceptible impact on the luminescent world of his art. In his garden, with Marthe, nothing else mattered.

UPDATE:

See also Michael Kimmelman, Pierre Bonnard Retrospective at the Musée d'Art Moderne in Paris (New York Times, March 30).

2 comments:

16 years old? Those French. Very nice piece Monsieur.

Amazing Dr.D.Sad I wasn't with you!

roomie

Post a Comment