Alles Vergängliche: Ozawa's Mahler Eighth

G.Mahler, Symphony No.8, S.Ozawa / Boston Philips      G.Mahler, Symphony No.8, S.Ozawa / Boston Decca      G.Mahler, Symphonies Nos.7 & 8, S.Ozawa / Boston Decca (Japanese Import)     |

This is far and away the best recording of Mahler's 8th, owing to an intensity (especially in the last movement) that is not matched by even the best of contenders (Abbado/DG oop, Bernstein/DG, Sinopoli/DG oop, Wit/Naxos, and with reservations: Kubelik/Audite, Nagano/HMU). This is the Solti antidote. For all those who don't understand why the famous Solti Decca recording (great sound, good singers) is so hyped by the (English) press, here is what they need. Unlike Solti, who does not seem to understand the drug-hazed Goethe’s Faust II or, indeed, the abstruse mysticism of the Mahler 8th, and consequently energetically drives through it with elan, speed, and determination (all good qualities in most other works, but not here), Ozawa gives this – frankly weird – work all the time it needs to develop.

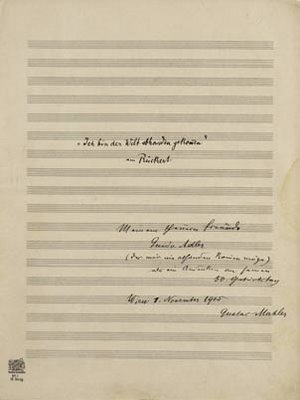

Not excessively so, either – 80 minutes is enough for him and not all that much, on paper, to spend on this work. Ozawa does not let it sag but rolls out the wafty, nebulous, foggy, misty parts so tenderly, in a way so other-worldly (and with no audible gear changes whenever he nudges the work forward again), that in a very eerie, beautiful way, time seems to stand still. After a mighty, powerful, broad Veni, Creator Spiritus (23:07), a marvel itself, he lunges into Faust II. Although ‘lunge’ is probably not the proper word: he carves it out of the score and, supported by a cast of singers that, seemingly infected by the momentous occasion, outdo themselves, delivers the most satisfying reading of this second movement. Better yet, he crowns it with an indescribably perfect Chorus Mysticus. For me, a performance of the 8th stands and falls with “Alles Vergängliche,” and Ozawa’s 6:02 are like a one-way ticket to heaven.

Whatever negative things have been said about Ozawa’s Boston Mahler (his Saito Kinen 2nd is actually excellent; the 9th with that band very good, too), this performance alone should have redeemed him. In Japan it was inducted into the “Philips Super Best 100” [sic!] collection, while in the West it still awaits reissue. I cannot quite understand why… but then I don’t understand the obsession with the inappropriate Anglo-drive through this work à la Solti or Rattle. The most recent Mahler 8th issued – with Antoni Wit and the Warsaw Philharmonic on Naxos – is currently the only recording easily available in the U.S. that comes close to Ozawa’s splendor. The timings, incidentally, are similar: 6:25 for “Alles Vergängliche,” 23:56 for “Veni, Creator Spiritus” – although minutes and seconds rarely tell the whole story about a Mahler symphony. Available alternatives to Wit, lest you get Ozawa directly from Japan, are Bernstein in the DG box of Symphonies 8, 9, 10, and Das Lied, as well as Kent Nagano’s broad HMU recording.

[Post Scriptum 2021: Not much had changed, 10 years down the line when I wrote this article on Forbes.com about the best Eighth, but at least one new, very surprising alternative had emerged.

True, the first movement is a bit muffled and orchestral details are occasionally hard to hear, but even here it is a compelling performance. But where my ears really began flapping and my prejudices crumbling is the second movement, up there with the very best, in terms of atmosphere, pacing, and singing – courtesy Wiener Singakademie (not to be mistaken with the more famous Singverein) and the cast of soloists.

Follow @ClassicalCritic

[Philips - Japan: Mahler, Symphony 8. Boston Symphony Orchestra, Seiji Ozawa / Faye Robinson (soprano 1 and Magna Peccatrix), Judith Blegen (soprano II & Una poenitentium), Deborah Sasson (soprano III & Mater Gloriosa), Florence Quivar (alto I & Mulier Samaritana), Lorna Myers (alto II and Maria Aegyptiaca), Kenneth Riegel (tenor I and Doctor Marianus), Benjamin Luxon (baritone & Pater Ecstaticus), Gwynne Howell (bass & Pater Profondus) / Tanglewood Festival Chorus, Boston Boys Choir / Joseph Silverstein (solo violin), James Christie (organ)]