#ClassicalDiscoveries: The Podcast. Episode 001 - Jeanne d’Arc & Walter Braunfels

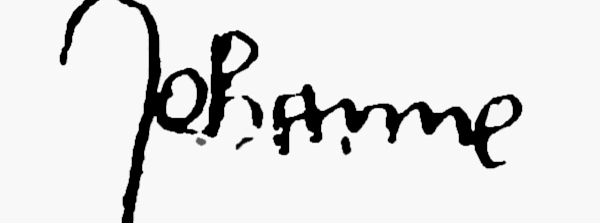

Welcome to #ClassicalDiscoveries. There is a little introduction to who we are and what we would like to achive at the first (or rather "double-zeroëth" episode). It still bears mentioning every time that your comments, criticism, and suggestions are most welcome, of whatever nature they may be. Now here’s Episode 001, where we’re talking about Walter Braunfels and his opera Jeanne d’Arc on the occasion of Capriccio having released the 2013 Salzburg performance which I reviewed for ionarts. (I also reviewed the fab Decca recording of this opera, here.) And now unto the thing itself, if you are intrigued:

Follow @ClassicalCritic

W.Braunfels, Te Deum,

W.Braunfels, Te Deum,