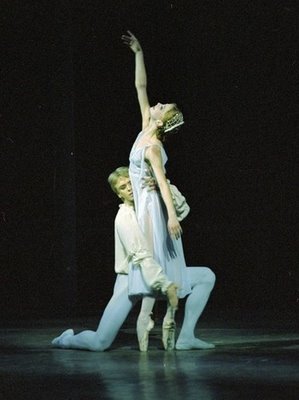

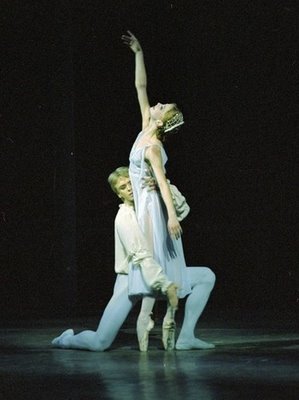

Andrian Fadeyev and Evgenya Obraztsova in Romeo and Juliet, Kirov Ballet, photo by Natasha Razina, courtesy of the Kennedy Center |

The

Shakespeare in Washington festival continues this week with the visit of the

Kirov Ballet to the Kennedy Center Opera House. This year, the resident troupe of St. Petersburg's

Mariinsky Theater has brought its

traveling production of Leonid Lavrovsky's choreography of

Romeo and Juliet. Sergei Prokofiev wanted to premiere the sublime music of this ballet (op. 64) at the Mariinsky in the 1930s, but the theater ultimately balked. The Bolshoi Theater in Moscow subsequently accepted and then rejected the ballet, because of the challenging score.

The Kirov Ballet's debut of the work was delayed until 1940, two years after Prokofiev introduced it in Brno. Even so, there is little doubt that the Kirov "owns" this ballet, in a sense, and it has been performing Lavrovsky's Soviet-era choreography regularly ever since. The Post

reports today that

Mark Morris will create his own choreography of this ballet, which restores the happy ending of an early version, made by consultation with a score recently discovered in Moscow. Lavrovsky ingeniously resolved several problems in adapting the Shakespeare play to ballet, and the death scene is one of the most moving parts of this beautiful work. Romeo lifts Juliet's apparently dead body from the funeral bier and carries her around, trying to partner with a dead weight.

If viewers are to believe the story, we must be moved by the idea of the two principal dancers falling in love at first sight. Last night's Juliet was Olesya Novikova, and with her long body, impressive extensions, elegant

port de bras, and flawless

en pointe technique, she was a fragile, wispy thing as Juliet. Novikova has only recently moved from the corps de ballet into solo roles,

memorably in a touring version of

Don Quixote. This was her Kirov debut in the role of Juliet, and it was to my eyes an impressive success. Novikova was perhaps not well paired with Byelorussian

Igor Kolb, who seemed not quite the right match by height. Kolb has been a principal dancer with the Kirov for nine years and is formerly known for the role of the Troubadour in this ballet. His strength in the lifts was remarkable, especially in the final scene, when Romeo carries the limp body of Juliet over his head back up the stairs to her bier.

Fine performances were also seen from Sergey Popov as Paris (whose tall body and lanky grace seemed to match Novikova's Juliet better), Dmitry Pykhachev's rash Tybalt (complete with red hair and costume of brightly colored patches), and Alexander Sergeev's slightly crazy Mercutio. The

corps de ballet provided interesting crowd scenes, although the four jesters that appeared with the Joker (an impressively acrobatic Andrey Ivanov) were not always in unity.

The Opera House Orchestra, conducted by the Kirov's Alexander Polyanichko, got off to a rough start (the synthesized organ that sounds at the start of the balcony scene has to go) but was in fine form by the third act. The final part of the score has the best music, beginning with the earth-shaking introduction to Act III, a contrast of dissonant and consonant chords. The low brass gave excellent force to the most famous theme, the menacing

Dance of the Knights. In this version, a snarling Lord Capulet dances with the men at the party crashed by Romeo and Mercutio. The theme comes to represent Capulet's domination of his daughter, returning as he scolds her for not agreeing to marry Paris in Act III. When Juliet appears to relent, while secretly planning to fake her suicide, and dances with Paris, the theme appears in the most seductive music of the ballet, a softened version for a

pas de deux with tinkling celesta.

Classical ballet companies tend to use the same productions over and over, which sometimes makes you long for some fresh air. The sets and costumes used here were designed for the original production by Pyotr Williams, who died in 1947. Except for the lovely outdoor night scene for Juliet's funeral, with its twinkling stars, some updating might be good. These few minor faults are easily forgiven, however, making it worth your while to see one of the remaining performances. For someone new to ballet, it will be an entertaining introduction.

Additional Comments by Jens F. Laurson:

Rarely is ballet musically so satisfying as to merit attendance on those grounds alone. Exceptions exist: Coppelia, most Tchaikovsky ballets (for those who like that sort of thing), and most definitely Romeo & Juliet, which the Kirov Ballet currently presents at the Kennedy Center. Prokofiev’s score makes this work an attraction for music- and ballet-lovers alike. The former get to hear all the music rather than just the popular excerpts and suites – and get to see the music they do know in the context for which it was composed. Rarely is ballet musically so satisfying as to merit attendance on those grounds alone. Exceptions exist: Coppelia, most Tchaikovsky ballets (for those who like that sort of thing), and most definitely Romeo & Juliet, which the Kirov Ballet currently presents at the Kennedy Center. Prokofiev’s score makes this work an attraction for music- and ballet-lovers alike. The former get to hear all the music rather than just the popular excerpts and suites – and get to see the music they do know in the context for which it was composed.

About that context, though… it is a very curious thing how much of Prokofiev’s music does not actually seem to go along very intuitively with the Leonid Lavrovsky choreography or even the story. This is particularly odd given the collaboration between the two artists on this work. Most notably the ‘threatening’, gloom-and-doom music that appears in the fifth scene of Act 1: It reminds, if anything, of Peter and the Wolf, with the wolf (or serious harm, at any rate) approaching. On stage, however, takes place a courtly dance, the most threatening move of which is a little twirly-tippy thingy of the foot that the dancing Capulet Family engages in.

Elsewhere the music and choreography mesh better – for example in the act opening scenes in which common folk dance: Their movements are angular, rough hewn… and although not primitive by any stretch of the imagination (not, at any rate, considering that Le Sacre du Printemps predates Romeo & Juliet by over two decades) they are not refined either. The ballerinas, who I first thought to blame, carried their dances out with such vigor that, in combination with the music, the effect was appealing and even captivating.

Charming as all that may be, it is the principal dancers that most ballet lovers come to see. The Kirov’s habit of milking the maximum amount of money from their Western tours (bringing the best dancers to London but no further and stuffing the orchestra with second and third-rank players – neither brass nor strings were up to the challenge [Correction: These third-rate players turned out to be the WNO orchestra] -- often leaves discriminating audience members disappointed. (The Bolshoi, by contrast, travels abroad with most of their stars.) With the cast from the 16th of January, no one could possibly have been much disappointed. Andrian Fadeyev’s Romeo had some awkward lifts – but that was the only detectable flaw in an otherwise convincing and elegant performance. Leonid Sarafanov Alexander Sergeev’s Mercutio had his moment in which he could show off, and there he absolutely dazzled - before falling down dead. (Mercutio, that is, not Mr. Sergeev.) The clunkiness of the lanky prince to whom Juliet is promised may not have been pleasing in-and-of-itself, but befit the character and the story very well.

But most of all this Romeo & Juliet was an opportunity to admire the dancing of Evgenya Obraztsova. Her Juliet was the kind of performance that one goes to the ballet for, in the first place; the kind of performance that one will judge all future ones against… and the reason why all those consequent performances won’t quite thrill anymore. Grace and skill are – or should be – the sine qua non of any good dance performance. Neither are enough, though, to make for the impression that Ms. Obraztsova left. Here grace and skill were married to dramatic ability, innate elegance, and an expression that was so natural and believable that an actress in a film could not have been more convincing. With her lithe, small body and her clean, fragile lines, her body language (from facial expressions to hand gestures), this was Juliet: A truly thirteen-year-old girl, impetuous, playful, young-in-love and in equal parts innocent and wilful. Superb – and the stuff that can convert ballet skeptics into fans. |

The only tickets remaining for the Kirov Ballet's Romeo and Juliet

are for performances tonight (January 18, 7:30 p.m.), with Olesya Novikova and Anton Korsakov, and Friday night (January 19, 7:30 p.m.), with Maya Dumchenko and Mikhail Lobukhin.