CD Reviews: Erkki Melartin / New York Polyphony

Charles T. Downey, CD reviews: Neglected Finn merits a closer listen

Washington Post, September 9

SEE ALSO:A composer as good as Erkki Melartin should be better known. I, at least, have not heard any Washington ensemble perform this Finnish composer’s music in the past decade, although it has occasionally cropped up at places such as Bard College, where Leon Botstein champions less-performed composers. This recent release from the Ondine label, which recorded Melartin’s six symphonies two decades ago, features excellent world-premiere recordings of three more of his works. Let jaded listeners who thought they had nothing new and beautiful to discover rejoice.

E. Melartin, Traumgesicht (inter alia), S. Isokoski, Finnish Radio Symphony Orchestra, H. Lintu

(released on June 10, 2016)

Ondine ode1283-2 | 56'50"

Melartin (1875-1937) composed his tone poem “Traumgesicht” (“Dream Face”) in 1910, adapting his own incidental music for a Symbolist play from five years earlier. Hints of the harmonic style of Debussy abound, evoking the murky world of Gabriele d’Annunzio’s “Un sogno d’una mattina primavera” with ethereal combinations of instruments. At the same time, there are soaring, chromatic moments of full-bodied sound — a reminder that Melartin’s teacher in Vienna, Robert Fuchs, also taught Mahler, Sibelius and Korngold.

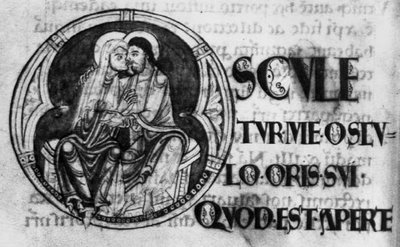

The second piece, “Marjatta,” brings in elements of Finnish nationalism. The redoubtable Finnish soprano Soile Isokoski deploys a shimmering high range, veritably purring on the high, soft B-flats in the opening description of silvery birds singing — and it gets even better from there. This orchestral version, premiered in 1915, features more iridescent orchestration as backdrop to an odd story of Marjatta, drawn from the end of the “Kalevala,” the Finnish national epic, about a girl who miraculously conceives a son by eating a lingonberry.

The latest of the three works is “Sininen helmi” (“The Blue Pearl,” Op. 160). The first full-length ballet written in Finland, it premiered in 1931. A prince, shipwrecked on an island in the South Seas, fights a giant octopus to win the magical blue pearl in its crown, as well as a princess the monster is holding captive. Hannu Lintu, who conducts the Finnish Radio Symphony Orchestra in these fine performances, has made an arrangement of pieces from the ballet’s first two acts.

Highlights include a gossamer-delicate “Danse des Nénuphares” (“Dance of the Water Lilies”) and the delightful number for the “Poissons à voiles” (“Long-Finned Goldfish”), which combines languid strings, harp-like piano and tinkling percussion. The only regret is that the disc doesn’t feature the entire score.

In 2006, New York Polyphony formed as an all-male vocal quartet specializing in Renaissance polyphony, in the style of the Hilliard Ensemble and other groups. After all, most of this repertory was intended for all-male ensembles, with either boys or countertenors on the top part.

Roma Æterna (Guerrero, Palestrina, Victoria), New York Polyphony

(released on August 12, 2016)

BIS-2203 | 72'07"

In the group’s first few years, its sound was good but not yet thrilling. In its latest release, however, with new singers on the middle parts and the excellent sound engineering of the Swedish label BIS, the puzzle’s pieces finally fit together.

Two masterful, often-recorded settings of the Latin Ordinary, by Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina and Tomás Luis de Victoria, provide the frame for a handful of motets and Gregorian chants, giving the partial impression of two complete Renaissance liturgies.

Pitch frequency was not standardized in the Renaissance. Therefore, transposing this music to a range most comfortable for the singers of a given group is perfectly authentic, as well as just making sense.

Palestrina notated his “Missa Papae Marcelli” in a high key, suitable for the boys singing the highest part. To make that top part work for its countertenor, New York Polyphony transposes the pitch down by a perfect fifth, which shifts this music completely into the darker, heavier male range, with the four lowest parts sung by baritones and basses. The tenor Andrew Fuchs and bass-baritone Jonathan Woody join the quartet for this six-part Mass, and the countertenor Tim Keeler takes the second soprano part that’s woven into the glorious triple canon of the “Dona nobis pacem.” The same singers do an equally beautiful job with Palestrina’s six-part “Tu es Petrus,” on the crucial papal text inscribed in giant letters around the dome of St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome.

Even transposed down a step, however, Victoria’s “Missa O quam gloriosum,” for four voices, does not sit quite right for countertenor Geoffrey Williams. It is complemented by Victoria’s and Palestrina’s disparate settings of the antiphon “Gaudent in coelis,” written for the feasts of multiple martyrs; the ensemble gives long-breathed drive to the ecstatic, overlapping repetitions of the words “exultant sine fine,” as the martyrs rejoice ceaselessly in heaven.

The disc ends with a Palestrina classic, the motet “Sicut cervus.” The balanced, rarefied sound of this recording, captured in St. Cecilia Cathedral in Omaha, is another reminder of the rewards that can come from meeting older music on its own terms.

Gabriele d'Annunzio, Un sogno d'una mattina primavera