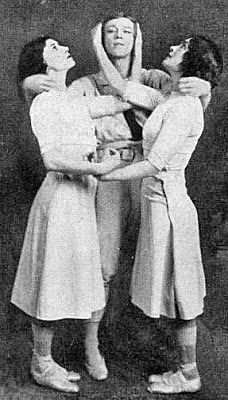

Tamara Karsavina (first young lady), Vaslav Nijinsky (young man), and Ludmilla Schollar (second young lady) in Jeux, 1913 |

As Vaslav Nijinsky recounted in some detail in his diary, Diaghilev's original idea for the ballet was a scenario about a homosexual encounter involving three men. In recognition of the difficulty such a story would have posed, even for the audience of the Ballets Russes, Nijinsky altered the story instead to an erotic meeting of a young man, danced by Nijinsky himself (at one point, to underscore the ambiguity of the situation, he planned to dance the role en pointe in women's ballet shoes), and two young women. To emphasize the playful nature of these events -- the title means "Play" or "Games" -- the action unfolded during a tennis match on a dusk-darkened court.

Somewhat incredibly, we have reviewed the piece live only once in the history of Ionarts, at a concert by the San Francisco Symphony in 2006. The orchestration of Jeux is among Debussy's most vivid, with glistening string divisi and knotted winds -- the whole-tone chord clusters in the prelude, which return more than once in the score, are one of many unforgettable mottos. Myriam Chimènes, who edited the score of Jeux for the Debussy Edition Critique, wrote about the timbres in the score at length for an article in Debussy Studies. She quotes Debussy writing to Andre Caplet about the score: "How was I able to forget the troubles of this world and write music which is almost cheerful, and alive with quaint gestures?" He also described the sort of orchestration he was looking for (he completed the piano score first, as was his usual practice): "I'm thinking of that orchestral color which seems to be lit from behind, of which there are such wonderful examples in Parsifal."

Debussy, Jeux (inter alia), Orchestre National de Lyon, J. Märkl (Naxos, 2008) |

Many recordings of Jeux have been in my ears, and I like many of them, including Boulez (Cleveland Orchestra, DG), Maazel (Vienna Philharmonic, RCA), the languorous Charles Dutoit (Orchestre Symphonique de Montréal, Decca), and the slightly nervous Christian Thielemann (Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra, live in 2002). My favorite at the moment, however, is a recent recording by Jun Märkl and the Orchestre National de Lyon, in the first volume of their complete recording of Debussy's orchestral works. The sound is beautifully detailed and captures a vividly nuanced reading, with all of Debussy's many tempo changes -- one every two bars, as one wag once jokingly put it -- given a fluidity like few others. While some hastier performances can come in under 19 and even under 18 minutes, Märkl's luxurious pacing extends out to 19:25, while still keeping the "dance" episodes -- playful evocations of the waltz and other forms -- energized.

Jeux is thought to be the first ballet ever danced in contemporary dress, with the costumes by Léon Bakst based on early 20th-century tennis outfits. You can watch an attempted reconstruction of Nijinsky's choreography, via the invaluable YouTube: Part 1 / Part 2 / Part 3. I had hopes for a production of the ballet this year for the anniversary, but it has not happened yet -- the Washington Ballet's last performance of Jeux was over 20 years ago. For further reading, Richard Buckle's Nijinsky: A Life of Genius and Madness brings together some newspaper pieces from around the time of the premiere, including reviews and an interesting interview that Nijinsky gave to Gil Blas about the piece. In a chapter ("L'Adorable Arabesque") in her book Mallarmé and Debussy: Unheard Music, Unseen Text, Elizabeth McCombie has written a sophisticated comparison of Debussy's score for Jeux to Stéphane Mallarmé's disruptive poem Un coup de dés, in which the poet claimed he was after something like the effect of words given timing like "music heard in concert."

No comments:

Post a Comment