My first Wagner opera was Parsifal at the Bavarian State Opera. Around Easter, twelve years ago, I managed to snag a standing room ticket for a performance with Waltraud Meier and Kurt Moll (John Keyes was Parsifal, Christof Prick conducted). At the time, Peter Konwitschny’s production was already six years old, and it fascinated me, right through my enthralled incomprehension.

I might not have been quite as enthralled, had I not managed to finagle my way onto a seat, front row, from which to follow acts two and three… and in the end, the Wagnerian glow I carried away from the experience was 46% pride of not having fallen asleep.

I revisited that particular Parsifal seven years later, and again this year… still the same production with its vast, stage-dominating tree and little else. It is one of Konwitschny’s more sparse productions, his first great Wagner-splash, and when compared with the multi-layered Stefan Herheim interpretation (see: “Bayreuth 2012: Parsifal, a Gift of Greatness”), it genuinely comes across as an entirely different opera. Where Herheim engages in story-telling and centers (one can’t properly speak of “focus”) the story around Gurnemanz and Kundry, Konwitschny zooms in on

the individual as such and pain—and puts Amfortas front and center of his all-white papier-mâché stage to illustrate this point.

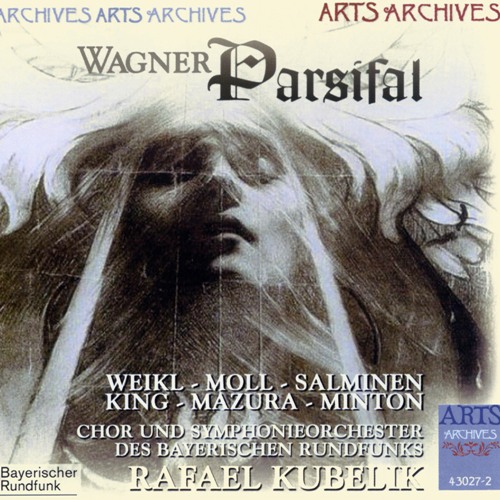

R.Wagner, Parsifal, R.Kubelik / BRSO Music & Arts       R.Wagner, Parsifal, P.Boulez / Bayreuth O&Ch. DG     |

John Tomlinson had to cancel the afternoon of the performance, which caused some difficulties. There’s a distinct dearth of Gurnemanzes in Germany on Easter Sundays. Especially during a Wagner bicentennial. Finally they found someone willing and able in Attila Jun, who hopped on the train from Stuttgart and was ready to sing from the side of the stage while Tomlinson acted the part out on stage. Since Tomlinson also mouthed the text, there was a whisper-like pre-echo of the music coming from the stage, sounding something like a nervous snake might. The sense of surrealism passed and eventually the ears got used to it, or Tomlinson laid off the consonants a little.

Petra Lang’s Kundry was meticulous, enunciation-perfect (appropriate for a rôle shaped by Waltraud Meier), well acted, but with a touch of a harmlessly earnest quality that was particularly at odds with her first act entry, scooting down the near-horizontal tree on a wooden horsy. She was a bit thin around the low notes, but just fierce enough everywhere else, and almost too charming-looking for the part: Pleasantly odd or oddly pleasant.

When Parsifal entered, a double—not the barrel-shaped Michael Weinius—swung across the stage, Tarzan-like. If memory serves, John Keyes had done the stunt himself. But when Weinius took over he showed great acting where he lacks athleticism: with subtle gestures and minimal means he mimicked the rambunctious, crude, self-made warrior-fool. Then, in noble contrast, he added a beautiful and elegantly employed voice; none too big and—all importantly—never trying to be bigger than it is.

Kent Nagano’s time in Munich is coming to an end, which brings with it a more explicit show of approval of whatever he does. He got ‘Bravos’ for this Parsifal, too, but good conducting and excellent playing from the orchestra really aren’t enough for this opera. The music of Parsifal is at least two fifths smell, and Nagano is scent-neutral. Not hospital-ward smell, as the anti-Nagano cliché goes, but neutral and in this case without inner tension. That’s good in some repertoire; great even. But it’s a quality wasted on this strangely sensual opera.

Konwitschny’s production still holds up—the same of which cannot be said of the realistic swan-prop, which is in a sorry state even considering the animal is supposed to be dead. Its neck is now broken in eight places, and it sheds feathers at every handling.