Easter Pilgrimage - Bach in Narden

Classical WETA, Wednesday, 3.20.08

There is value in tradition itself and while I would not want to have to justify how, much less why, I know it to be so when I revel in a decorating a tree in late December or not eating Bavarian white sausage after the bells have struck noon, or walk on the street-side of the sidewalk. There are no compelling reasons – spiritual, gastro-hygienic, safety related – to any of these, yet I cherish and value them.

Listening to music for certain occasions, too, is a tradition for me. Some are simply private or regional ‘habits’: Baroque on Sunday morning, Die Fledermausfor New Year’s Eve. Others are contextually related. Among those is listening to Bach’s St. Matthew Passion or Wagner’s Parsfial for Easter. I cherish the music on it’s own, of course, but I especially relish the sense of occasion and the tradition. This is something possible to experience whether you consider Easter’s significance to rest chiefly on the presence of Easter bunnies and marshmallow chicks or the Passion of the Christ.

One element of great art is that it taps into that “oceanic feeling” (Romain Rolland), our resonance to matters spiritual – whether dye-in-the-wool secularist, incense-wafting mysticist, or someone of (traditional) faith.

I don’t mind repeating myself when I say that Bach, more than any other composer, does that for me as well as many, maybe most, of those familiar with him. (Wagner: not so much… he seems rather to evoke a sort of cultism – which is related, but not as rarified.) So my trip to and through five European cities, chasing Matthew Passions (and Parsifals, more of which later), really is a Bachian pilgrimage for me.

Admittedly conveniently train-bound, with the musical pit-stops at its heart, rather than a distant shrine of a goal. But the route has always been an important part of any pilgrimage. Indeed, the words “roam”, “saunter”, and “canter” are derived from describing people on their pilgrimages to Rome, Sainte Terre, and Canterbury, respectively. At the end of it is not necessarily a cathedral, or temple, or menhir, or Stratford-upon-Avon, but renewed life or, more modestly, revitalized hope, rejuvenation. So priketh me nature in my courage and I longëd to go on this pilgrimage.

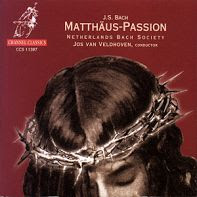

The little Dutch medieval fortress town of Naarden, completely surrounded by a wall and moat, was the first stop, a highlight unlikely to be topped by successive Matthew Passions this year. Since 1921 the Matthew Passion is performed at the Grote Kerk (“Great”, or “Large Church”) in Naarden. The Nederlandse Bachvereniging is responsible for the performance. That name and their current director Jos van Veldhoven are familiar to me from their recordings on Channel Classics. Their Mass in B-minor from last year not only made it onto my best-of-2007 list but has quickly become a favorite version.

High expectations were hardly disappointed. While I was not as moved and grabbed as I always hope for, that might have been due to recent overexposure. It was in any case so good – so exceptionally good – that the delight it brought made up fully for this. (Interestingly the memory of the concert has since only appreciated, and glows warmly in the Bachian recesses of my mind.)

From the first notes on, Veldhoven and his forces (two orchestras with altogether ten violins, a viola, one cello, one double bass, two traverse flutes, two oboes, a recorder, continuo organ, and bassoon each, and a theorbo, viola da gamba, and harpsichord) established this rendition as superior. The ensemble work was perfect with all six violins of the first orchestra playing, breathing, and living the music as one. The tone of this HIP (Historically Informed Performance) group sweet and sonorous like one could hardly expect from an indulgently romantic Viennese group, much less an original instrument band.

Johannes Leertouwer’s violin solo (“Erbarme Dich…”) was filled with warmth, a light vibrato on held notes, perfectly in tune and proved altogether better and more accurate than anything I have ever heard, say, Pinchas Zukerman do lately. The following duo with alto Matthew White (pleasantly masculine sounding, near his limits in the upper register but never of that whiney, namby-pamby quality that turns so many ears off counter tenors) had me in awe of the musical excellence. Antoinette Lohman’s solo for the opposing camp of violins was a study in contrast to Leertouwer’s mellifluous, sweet sound: Very engaged, wiry, agile, and energetic.

The boys’ choir employed for the chorals consisted of but three trebles. They may have been nervous, but either need not have been – or perhaps that nervousness actually aided their pinpoint accuracy. I have had my share of exposure to boys’ choir singing – active and passively – and I don’t think I heard three voices so together and accurate. In the generous but appropriately dry acoustic of the Grote Kerk they produced a sonorous, even voluptuous sound that I would not have thought possible. The fact that even the tiniest inaccuracies in their presentation were immediately audible only assured that the achievement was all theirs, not due to some unique acoustic phenomenon of the venue or their placement in front of conductor and orchestra, vis-à-vis the pulpit.

There were three, four very minor quibbles with the whole performance not worth the time or space to mention, since the overall excellence of Veldhoven’s and the Netherlands Bach Association’s achievement cannot be overstated. Of course the soloists had their part in this too: All were at least good, but next to Gerd Türk’s evangelist, Dorthee Mileds and Maria Keohane (sopranos), Matthew White and Williams Towers (countertenors), Julian Podger and Charles Daniels (tenors), and Wolf Matthias Friedrich (bass), it was Andrew Foster-Williams whose Jesus stood out for his very impressive, indeed: ideal rendition.

Towers could not quite match White’s performance, but he came close in the unrestrained and unconstrained, beautifully shaped aria “Können Tränen meiner Wangen…”. Türk had a few rough patches, his singing somewhere between lovely and routine, maybe both. Charles Daniels, recently heard in Koopman’s Mass in B-minor, was at the same high level of accomplishment without going beyond it – his colleague Podger rather excitedly sang the recitative “O Schmerz!” and found himself near his limits before the absolutely phenomenal, pitch-perfect oboe solo interrupted him. Dorothee Mields’ vibrato was a little heavier than I would have expected, but it was still clear and uncommonly beautiful, strong, and secure.

Ripienist Marjon Strijk’s Uxor Pilati, with an angelic ring to her strong soprano,proved on behalf of all her colleagues the high quality of the choir which sang the chorales together with the soloists. Together, they made for a group of 24 singers that sounded very sizeable in this venue and yet retained the clarity and precision rightly cherished in good HIP performances. Gerd Türk joined in as the finale chorale – “Wir setzten uns mit Tränen nieder” (“We sat down with tears…“) – let us back out into the clear night in Naarden, journeying back to nearby Amsterdam. A conspicuous beginning of the Easter Pilgrimage, indeed.

Impressive – or frustrating – in their own way were two performances at Amsterdam’s Concert-Gebouw. National Symphony Orchestra principal guest conductor Iván Fischer steered the – obviously reduced – forces of the Koninklijk Concertgebouworkest through a performance that was long on beauty and short on excitement. The performance made no pretensions of being authentic in any way, but even traditional performance did not escape the HIP trend: The strings were out in nearly twice the numbers that Veldhoven used, larger but still modest. The choirs boasted 42 throats and 27 trebles altogether. The soloists sang in a style cut from a more romantic cloth, more liberal with their vibrato and dramatic delivery.

This will either please or annoy. For me the sense of – and familiarity with – the occasion as such, made it pleasing. To sit in the Concert Gebouw early on a Sunday and to revel in the smoothed sounds of Bach, delivered with sheen and humble pleasantry, gave a sense of civilization being a wonderful thing… as if there was something fundamentally right with humanity, after all. This sense of gathering at a temple of the arts, of mimosas, of mothers using their heavy perfume, of the children hardly fidgeting for two hours: it’s a sort of Lake Wobegone idyll, except with culture instead of ice-fishing at its center.

Mark Padmore’s evangelist was in excellent voice, as were alto Bernada Fink, mezzo Wilke te Brummelstroete, and soprano Johanette Zomer. Kristinn Sigmundsson, who filled in as Jesus, was a wooly disappointment, his bass colleague Zeert Smits did better, but came close to belting with his huge voice.

All were very dramatic and employing a vibrato that will strike unrepentant HIPsters as inevitably inappropriate, but then the purpose of this performance was not to strive to an alleged ideal of authenticity but to aim for maximizing beauty. Where someone like Veldhoven can combine the two – absolute beauty as well as HIP explosiveness – that combination is always going to win out over just one. When excitement and beauty are an either/or proposition, the preference is subjective. The very gentle and genteel way this Passion was performed by choir and orchestra, with the corners rounded off and edges smoothed, appealed more to me than the performance later that Sunday, where the Combattimento Consort Amsterdam, the Nederlands Kamerkoor, and the Roder Jongenskoor under Jan Willem de Vriend presented the other alternative: More passion in the Passion, but a cast of soloists that was not terribly satisfactory, and orchestral forces that were enthusiastically engaged, but not precise.

I might have enjoyed this sweetly likeable performance more on any other day had I had fewer St. Matthew Passions preceding it and with less importance attached to the traditional element on the occasion. Especially so if Carolyn Sampson had not bowed out and if any other alto than the pseudo-operatic Ewa Wolak had taken those parts. Alas, that Sunday I was not inclined to appreciate freshness over smooth beauty.

From this dose of Dutch Bach, the pilgrimage went to Paris, where Parsifal under Hartmut Haenchen awaited at L’Opéra national de Paris – more about which I’ll get to write next week.

No comments:

Post a Comment