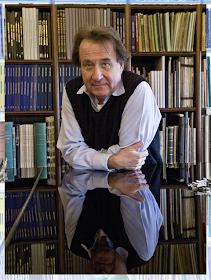

W_Gross.png) Rudolf Buchbinder sounds engaging to the point of jolly from the first note on. The Austrian pianist chuckles through his greeting, dispels any fears of having let him wait and inquires if I’ve got my tape recorder ready. It is, and so he immediately bubbles forth about the Dresden Staatskapelle, with just a little prod about what makes that particular orchestra so special: “This is one of the very few orchestras that stick to their tradition. In sound… especially in sound. They have a special sound in the winds, the woodwinds especially, and also in the strings. And, this must be mentioned, that they still play the operas of Richard Strauss [most of which the Staatskapelle premiered] from the first edition material.” This brings the avid collectors of scores to a favorite point, and he is easily encouraged when I naïvely ask if that makes much of a difference.

Rudolf Buchbinder sounds engaging to the point of jolly from the first note on. The Austrian pianist chuckles through his greeting, dispels any fears of having let him wait and inquires if I’ve got my tape recorder ready. It is, and so he immediately bubbles forth about the Dresden Staatskapelle, with just a little prod about what makes that particular orchestra so special: “This is one of the very few orchestras that stick to their tradition. In sound… especially in sound. They have a special sound in the winds, the woodwinds especially, and also in the strings. And, this must be mentioned, that they still play the operas of Richard Strauss [most of which the Staatskapelle premiered] from the first edition material.” This brings the avid collectors of scores to a favorite point, and he is easily encouraged when I naïvely ask if that makes much of a difference.“Look, well… I have twenty-five different editions of the Beethoven sonatas. And I tell you, I play from the first editions and not from the new ones.” How come? “Because this has nothing to do with Urtext [the term coined publishers for modern editions suggesting absolute and unique fidelity to the original intent of the composer].

What is written today. You know, for instance in Henle [the publishing house]: so many things are written in parenthesis like ‘Beethoven has forgotten the dynamics’ or something like this. It’s unbelievable what they write” he works up a very mild, sweetly-affectionate rage, “I just now played in Dresden opus thirty-one, number two [the "Tempest Sonata", various scores available at IMSPL], and Beethoven writes first fortissimo then forte and then nothing. Because after this come sudden sforzati to make a crescendo. What does Henle write into the score? Fortissimo, forte, and then a third forte in parenthesis. I just don’t understand how they can call that ‘Urtext’. The next problem is: in all these editions there are fingerings from absolutely stupid people. Perhaps you know that Franz Liszt was an admirer of Beethoven, and he made also a complete edition of the thirty-two sonatas. And we also know that Franz Liszt was not the worst pianist in the world. And there is not one fingering by Franz Liszt [in his edition], only those of Beethoven. So why are [the modern editors] not able to bring us the music as the composer has written it? Why do they always have to add something? I just have such a problem with Henle editors when they always have to add something in parentheses working on Beethoven or Mozart or Schumann apparently always forgot something. They forgot nothing! The idea that the repeat has to be precisely the same as the exposition [I’m getting an instant tutorial in the structure of the sonata form, just talking to Buchbinder] which is completely wrong… it always has to be different. I’ve often talked with Joachim Kaiser about this [a Munich critic of local fame, especially for his reviews of and writings about pianists], that there always has to be some little variation. Modern editions level all those small differences. That’s the problem with these editions and the Dresden Staatskapelle”—here his heart makes an audible leap after all this deplorable modern-edition business—“they still play from those original scores. One conductor, I don’t remember which one, asked them to play a Strauss opera from the new materials; immediately they threw it away and went back to the old editions, of course. Even if they are in bad condition, but never mind…”

Is there a curve, though, I wonder, where the very first editions are very good and then again the modern ones, even if you don’t like them particularly, are better than those in between?

“Oh yes, of course” he is busy to ascertain. “There were many mistakes in those. I told you about this part of opus 31/2”—an example that reoccurs in a lot of interviews, these days. “Fortissimo, forte, and then nothing by Beethoven. I have the edition by Eugene D’Albert. You know what he writes? Three times fortissimo.” He chuckles in disbelief and I feel compelled to chuckle along in that sympathetic sense of ‘Hear, hear! Did he now? What has the world come to.’ He responds with another grateful chuckle that suggest a modicum of pleasure at having found someone who grasps in some minor way the severity of this editorial transgression. “Yes, these are the sins that have been carried out against Beethoven in the past, of course. To write three times ‘fortissimo’, really, it has nothing to do with Beethoven, you know.”

But because I’m still not sure I’ve quite understood the complete magnitude of the dynamic problem at hand, I must reveal my ignorance by asking him: So when he—Beethoven—leaves out the last dynamic marking, where do you actually go?

Buchbinder is not prepared for such an inane question, so he kindly misunderstands it and replies: “Oh, I always go to the old editions.” I stumble to clarify: No, no… if you’re actually playing… [“Yes”], and you have fortissimo-forte-nothing… [“Yes”], where do you go dynamically?” Baffled at why I would ask a question when the answer is so painfully obvious he staggers: “Like… like Beethoven… ah, fortissimo, forte and then piano.” Ah, ‘nothing’ is piano. “Yes”. The sound of this “Yes” allows me to detect a slight decline of the earlier-gained esteem, but I am glad he doesn’t ask me if I work for Henle, surely the most severe reprimand Rudolf Buchbinder can think of. “Yes, there’s that diminuendo and less and less and then from this ‘nothing’ the development of these sforzati comes out much better than when you start with forte.”

Very well, but now I want to know how he would feel about it if Henle didn’t misread Beethoven but wrote ‘piano’ into parenthesis, would that still be… “Nothing!” he gurgles with humored indignation. “They write ‘forte’ [we share that fraternal chuckle again]. Yes, because apparently Beethoven should have written ‘forte’. Yes… well, you know, I spend days sometimes with the oldest people at Henle and show them all the mistakes they do.” And do they appreciate that? “Yes. But they don’t learn, you know. I was asked once by Peters—they wanted to make a new edition of Beethoven sonatas—and then there was the question: should we make a real Urtext or an interpretation edition. And this is the problem: they make a kind of compromise, having both in one. And you can make an interpretation edition, of course. But in the new Henle edition of the sonatas you can’t see Beethoven’s notes anymore because so much is written into the score in terms of dynamic ideas and fingerings and everything. This is an interpretation edition. That’s OK. But they shouldn’t call it Urtext. You know when some students from anywhere in the world, whether Japan or Uzbekistan, see this “Urtext”, they don’t see the parenthesis, they only see the ‘forte’ within. And of course for them the forte is original.”

Before I get to express full approval with that assessment, wondering how I might ever get the topic back to anything at all relating to his gig in Washington, Buchbinder continues on, randomly, jovial and without, apparently, the need to breathe between sentences: “…and coming back to the Dresden Staatskapelle, I think this is one of the best orchestras in the world today.”

Partly because of the distinctness of their sound? “Yes. You know, in our days there is one big danger which, on the other hand of course is very positive, and that is that all orchestras in the world today are very international. So the Vienna Philharmonic, say 50 years ago, only took on students from the Vienna Conservatory. In Berlin from the Berlin Conservatories. But in the meantime through immigration—you know, so many Europeans went to the United States… they founded schools, their students carry on with that tradition which is now a mixture all over the world. Actually have the same musicians all over the world today. Which is a very good thing, that, of course; but some orchestras lose their personal touch, their personal sound.”

We move on to conductors shaping sounds—“like [Eugene] Ormandy did in Philadelphia, what [Fritz] Reiner did in Chicago, what [Herbert von] Karajan did with Berlin” Buchbinder waxes nostalgically. There are not many sound-shapers left, though, I interject, which receives a hearty “that’s the main problem” from Buchbinder. And it gets us talking about Dresden, because “they are getting one of the few left.” We don’t mention Christian Thielemann by name, knowing who we are talking about.

“For instance, Lorin Maazel”—Buchbinder seamlessly shifts the conversation to Thielemann’s successor at the Munich Philharmonic—“chose all French players for the woodwinds when he headed the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra. Many French woodwind players came during his period.

What does he play beyond the great classical and romantic repertoire? Complete Mozart Concertos [the set being considered the finest by many critics], Beethoven Sonatas and Concertos, Brahms, complete Haydn Sonatas… his discography resembles that of Alfred Brendel in its focus.

“I played the Gershwin Concerto a lot with Maazel,” he adds to my list, showing he’s a bit more diverse than that. “It was his favorite concerto with me; I had to play it in the first season in New York with him.” Did he like it? “It’s one of my favorite concertos. Yes, yes, only the concerto, not the Rhapsody [in Blue]. The Rhapsody I play in recitals, only the original version [originally for piano and jazz band, though generally known in the version orchestrated by Ferde Grofé ], not with orchestra. And I play this between Bach and Mozart, I don’t mind.”

And how far do you go with the repertoire? Do you do any secret Second Viennese School on the side?

“Oh, yes, of course. I played all Schoenberg. I love to play the Berg Sonata [Opus 1, a particular favorite of mine], I play the Webern-Variations very often, and some composers also dedicated pieces to me and then I played them.” His enthusiasm on the latter point is nicely hidden. “The problem is today… oh, I played the Penderecki Concerto, for instance, quite often. Also with Penderecki. You know, it’s what made the 20th century so great for music: There was not one style. There are so many different styles for each composer. You cannot compare one with the other. An explosion of styles, which is fantastic. But one thing they had in common, altogether: Great personalities. And this is what we are missing today in music, in literature, in politics, wherever you take a look. We are missing great personalities.”

I am not quite convinced by that sort of argument, so I ask back: Do you think that people will be looking back at our age and say ‘oh my, that was the fifty years of missing personalities or will they oh I wish I were back in 2010, they had personalities, nowadays we have nothing…’

“You know the problem is—using the word nivelize again [it’s more appropriate word than ‘leveling’ to express the concept of ‘making-everything-the-same’] today everything is nivelized. If you look at the fashion, everyone looks the same. There is no personal touch and taste anymore. [I wince as I think of my colorful pochettes, ascots, and tweed trousers.] It starts with so many things. We lost it. How do you say: the individualism. We fight today against individualism and that is very dangerous.”

Well, isn’t it always both trends at once? Everyone tries to be individualistic and as a result everyone looks the same. Now it’s his turn to wince… “Naahmmmh… today, one does not want to stand out of the crowd.” (Buchbinder must live in a very different universe than I do.)

“People want to stay in line, are afraid… I was for over thirty years in Switzerland at the University of Basel and you know… in Switzerland everybody looks the same.” Now I understand; Switzerland—a people to make Germans look like perpetual hippies—is as close as you will get to a different universe without intergalactic travel. I grant him Switzerland, but he wants more:

“Yes, but this is more and more all over the world. Take a look at men, walking on the street. They all look the same. With the blue jeans and the jackets.” Now I really I feel like protesting, ready to cite myself as an example as someone who dresses decidedly unique. But just before I open my mouth I look down on myself and find myself wearing jeans and a suit jacket. I decide to postpone my counter-critique and listen to him continue “…the girls look the same… you see also with the Mango, H&M, and Zara… all these fashion chains. All over the world they are the same.”

…and yet the irony is that they succeed by promising individuality…

“Ja. You know, for instance, my teacher”—he switches topics on a dime—“[Bruno] Seidlhofer, his pupils apart from me—for over 15 years I was studying with him; also when I finished we continued a kind of friendship—but they were Friedrich Gulda, Nelson Freire, Martha Argerich… and what is the special thing about Seidlhofer? We are completely different. All of us. And he was fantastic at leaving each student’s individualism intact. I don’t like to talk about a ‘school’. It doesn’t exist. The ‘Viennese School’ or any kind of school of piano playing. Everybody plays his way. And this was the good thing of Seidlhofer, for instance, that he was not a teacher whose students all had to play the way.”

Interesting article, with valid points from Herr Buchbinder.

ReplyDeleteWhat I find slightly odious is the fact that he slammed Henle, but yet he didn't seem to mind getting paid from said publishers for posing with their products, in their 'Aritst Gallery' (on Henle's website)...

Oh, and by the way, proofreading errors mar an otherwise fine article, e.g. 'disbelieve' and 'Marta Argerich'

". . . I am glad he doesn’t ask me if I work for Henle, surely the most severe reprimand Rudolf Buchbinder can think of."

ReplyDeleteVery funny -- I laughed out loud!

I heard Buchbinder and the DS in Santa Barbara last week, playing Schumann's concerto and Beethoven 7. Buchbinder is terrific! This orchestra really is distinctive, as promised, and even on a night that was probably routine for them, turned in an exhilarating Beethoven.

Good stuff.

ReplyDeleteI'd be interested to know who are considered the (apparently few) "sound shapers" in classical music besides Christian Thielemann.

sound-shapers: few, indeed. i tend to think only of those whose sound i actually like 'as a sound'... but that's not to say that Simon Rattle doesn't create a very particular sound (unless you consider it merely the perfection of a 'neutral sound'). the shades of hushed gray that dominate Welser-Moest's work certainly are the result of careful tuning of his instrument. Chailly has a certain idea about sound that goes beyond the works he is playing at the moment. perhaps Dutuoit, in his Canadian days.

ReplyDeleteAgreed on lack of 'sound-shapers'. Granted, the real great maestri have their own stamp, but in my opinion, it takes work, work and more work to achieve a recognisable orchestral sonority. Barenboim says it as well, lamenting the lack of sonic identity in modern orchestras.

ReplyDeleteRattle is a great musician, but he does not actively work on the sonority of an orchestra per se. And I find it a real pity, especially for an orchestra like the Berlin Phil.

But Karajan, hands down, was one who did such work. Say what you will about him smoothing everything down, and even if he didn't create the "Berlin sound", he did refine and reDEFINE it. Through endlessly and actively searching for what he thought was good sound (again, in my humble opinion). For proof, just listen to recordings of him in rehearsal. He goes over and over again on passages, not only for the musical details, but subtle differences in sound to make a better sonic balance.

"What I find slightly odious is the fact that he slammed Henle, but yet he didn't seem to mind getting paid from said publishers for posing with their products, in their 'Aritst Gallery' (on Henle's website)..."

ReplyDeleteNote to Anonymous No.1:

Not Buchbinder, nor any other artist in that "Artist's Gallery" on Henle's website, gets paid for their appearances.

Agreed re: Karajan; that's why his 2nd Viennese School recordings are so f&#*$@ amazing.

Barenboim might be another one of those sound-shapers, now that you mention him. (In fact, I think he's most like Thielemann in so many aspects that it's rather funny and ironic.)

I was thinking of Muti, too... and I guess making everything sound homogeneous and boring could be considered a type of sound-shaping. :-) [I'm being somewhat unfair; his Prokofiev is without equal and the very opposite of boring...]

Agreed re: Karajan as the Ur-soundshaper, if you will :) Glenn Gould is the other. Gee, I wonder why the former is the best-selling classical artist of all time and the latter is I suspect the best-selling classical pianist of the 20th century.

ReplyDeleteI personally think it's a damn shame that we don't have more sound-shapers in classical music anymore. The whole industry is so afraid to take risks.

If Risk is what you want, do Daniele Gatti. As is the nature of risk, it doesn't always pan out... but I say: give the man a decent orchestra already (hint-hint: there will be decent one available the second Maazel kicks the bucket and wooing Gatti won't lack half as ridiculous as trying to get Andris Nelsons) and watch him shape and reign over creative chaos.

ReplyDeleteSo in your opinion, is Daniel Harding a sound-shaper?

ReplyDeleteI am 73, a well-trained pianist, myself, who never made a career, but who has been devoted to the study, performance and enjoyment of serious music for 65 years, even so.

ReplyDeleteI was astonished to discover Rudolf Buchbinder for the first time just a short while ago on YouTube. How this magnificent artist -- just a few years my junior -- escaped my attention all these years I cannot imagine, because in addition to daily practice I am an obsessive-compulsive listener devoted to the glories fo the past, but also forever on the lookout for newer, more satisfying interpretations.

At any rate, I cannot say enough for his playing -- powerful, warm, courageous, insightful, lyrical, deeply philosophical, utterly sincere, filled with manly vigor, spontaneity, affection -- it fairly throbs with a sense of immediacy -- as though it were being newly created on the spot.

Herr Buchbinder must be a wonderful human being. There seems no trace of conceit, arrogance, pretense or condescension his interpretations.

I have listened to everything of his available on YouTube several times, and enjoy what he does more with each successive hearing.

Why he is not better known in the USA tempts one to believe in conspiracy theories. Could the established powers, perhaps, be more than a bit jealous?

It would seem likely.

~ "Hyramess"

"Hyramess", much of what you say rings absolutely true. He's "world famous in Vienna", as they say, which is plenty for one career... and in any case has a splendid career going in continental Europe, too. And he's busy with his festival. As for why an artist is not more popular here or there... there are always so many factors. Perceived 'sexyness' by the promoters. Public response. Connections of the agent. Luck. Why isn't Alexandre Tharaud famous world-wide (esp. Germany et al.) but (rightly) a super-star in France and at least reasonably well known in the US? Every case is unique and merits looking into, for anyone interested in the vagaries of fame.

ReplyDelete