Taiko is considered a classical art form in Japan, not only of a martial character, but also of a spiritual one. I recall Igor Stravinsky once saying that African Ashanti drum music was a dialogue with the gods. There is definitely an aspect of this in taiko as well.

However, the attitude of this troupe, as expressed by Tao performer Taro Harasaki, is entertainment. “We call our show entertainment”, Harasaki says, “and it’s not a typical Japanese drum concert because the aim of Tao is to have the show on Broadway or in Las Vegas. It’s a very exciting spectacle.” And this is indeed what we experienced—tremendously exciting Japanese drumming, with a touch of Broadway show biz in the choreography and costumes.

The show also included some humor, which is decidedly not “martial.” However, things never descended to the Las Vegas level, an allusion to vulgarity and garishness that Harasaki may not have intended when he made his statement of Tao’s aim. (Come to think of it: How is the Guggenheim-Hermitage satellite in Vegas doing?) More accurately, Tao director Ikuo Fujitaka calls Tao a “modern respectable culture of drumming.” It certainly requires extraordinary discipline and coordination, which the members of the troupe achieve by practicing 10 hours a day in their semi-monastic headquarters in Japan.

During the two-hour show, Tao members used three massive, six-foot-circumference drums, called o-daiko, varied combinations of other drums, shinbue flutes, koto, gongs and cymbals, and Indonesian bamboo marimbas. But throughout the thirteen segments of the program, the drums predominated.

Sophistication and coordination are ever present, but express something fiercely elemental. To say it was rhythmically exciting would be an understatement. But for the intense discipline, it would be best described as orgiastic. Rhythm is one of the primary human experiences. It beats within us and in nature, and our response to it is an instinctive, involuntary one. That is what was so moving in this performance—the primal level at which the drumming connected with the audience. When the 12 drums in the Aokikaze number cut lose, there is no way your blood is not stirred. In Horizon, the drumming reached a martial pitch that could have led an army to victory or certainly convinced its enemy that its day of doom had arrived.

In Southi, dueling drums added some humor that perhaps would not have pleased a purist, but only a crank could say it wasn’t fun. Solo-Rhythm began with two of the huge drums thundering up stage; then a 5-drum combination unit appeared downstage. The soloist who played them for the rest of this number appeared to be the Japanese equivalent of Gene Kupra. He achieved an astonishing range, from the softest pianissimo to thundering triple-forte.

One of the few missteps was in the Maori number, during which the flautists seemed like they were lip-synching their instruments to canned acoustics. Were they using a recording? I wondered. No, but the unpleasant impression came from having their instruments miked—presumably necessary to not be drowned out by the drums.

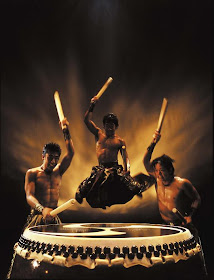

In the second half of the program, the Da (the beat) number seemed to be the real taiko for purists. Three drummers faced upstage the three gargantuan bass drums. Both the costumes and the choreography—highly disciplined and stark—conveyed a deep sense of ritual and the sacred. Here was the requisite severity and solemnity for commencing a dialogue with the gods. The drumming on these three massive bass drums reached toward the primordial—and achieved an overwhelming sense of something coming from the very bowels of the earth. I would have shouted bravo but one does not do that in a temple, which is where I felt I had just been. This number alone was worth the entire evening.

The last number, Queen, returned to the show biz world with pageantry and spectacle, flag waving and gymnastics that left the audience cheering on its feet. Designed to reach a broad audience, Toa’s “The Martial Art of Drumming” succeeded by any measure.

My 12-year old daughter said, “I thought it was going to be boring; it was just the opposite.” RRR

I saw the performance and missed getting a recording of their music after the show. Does anyone know where to order the music?

ReplyDelete