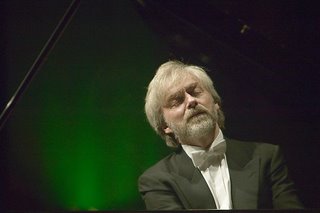

Krystian Zimerman's June 15th recital at Amsterdam's Concertgebouw featured unparalleled virtuosity in the works of Bach, Beethoven, Brahms, and Szymanowski as part of the Master Pianists Series. After a strongly worded announcement for the audience to keep very still and quiet for the concentration of both performer and listeners, Zimerman descended the long stairway to begin Bach's Partita in C Minor in a softly lit room.

Krystian Zimerman's June 15th recital at Amsterdam's Concertgebouw featured unparalleled virtuosity in the works of Bach, Beethoven, Brahms, and Szymanowski as part of the Master Pianists Series. After a strongly worded announcement for the audience to keep very still and quiet for the concentration of both performer and listeners, Zimerman descended the long stairway to begin Bach's Partita in C Minor in a softly lit room.Zimerman realized his ideal to always discover new frontiers of pianism: such a fascinating array of textures in the partita's multiple movements often came at the expense of simplicity as slow movements became mushy (at times over-pedaled) and some faster movements pushy. Zimerman remarked in a recent Financial Times interview that he often avoids practicing works he is planning to perform so they will be pristinely fresh on stage. Combining this with a high-speed train approach to Bach caused lines to become lost and the music to often railroad past the audience. Grand Romantic crescendos into final cadences, sounding as if the performer were strangling a baby, have been abandoned in HIP Holland now for decades.

Beethoven's Sonata No. 32 in C Minor provided more of a vessel to handle Zimerman's spritely virtuosity. In the final movement particularly, there were multiple musical moments of the sun bursting from behind the clouds. Zimerman youthfully exploited the entertaining qualities of this work as was the case in Brahms's Klavierstucke, op. 119. These four pieces -- Brahms's last for the piano -- lacked the often tormented\inner-struggle found in much of his oeuvre due to Zimerman's sweeping approach to the final three works. A heightened transparency was experienced in the first Intermezzo in B Minor with gorgeous falling lines. Zimerman played with pure abandon in the final Rhapsody in E-flat Major producing a full sound that the Concertgebouw's perfect acoustics accepted.

Szymanowski's Variations in B Minor on a Polish Folk Tune finally allowed Zimerman to shine as a master pianist. The theme is melodic, yet complex, with an underlying Scriabin-like, ambiguous harmony. Szymanowski is definitely a composer with whom one should become better acquainted. Here is a snapshot of my notes -- Var. 1: Right hand flying like a butterfly; Var. 2: Crazy octaves. It sounds like he has 8 hands, yet everything is sublimely beautiful as the walls shake. How does he get more clarity in this barrage of notes than in the Bach that opened the program? Var. 3: Szymanowski briefly quotes Chopin's Sonata No. 3; Var. 4: Soft and flighty; Var. 5: Dark funeral-march leading to ffff chords; Var. 6: A vast commotion with super-small arpeggiated notes, each sparklingly clear. Powerhouse; Var. 7: Bach-like and fugal. Bombast. Hitting everything with a grand ending.

Zimerman suggested he should play something either Italian or French as an encore. He announced the Second Movement of... but I unfortunately missed the name of the French composer. Zimerman gently allowed colors to merge and unfold as the primary driver of the piece.

Jaja, never underestimate a Bach piece...

ReplyDeleteOther than that, good review.

Ja hoor, what is your last name, Willem? You wouldn't happen to be the creator of the facebook group "Willem Mengelberg forever" Memorial Fan Club, and coiner of the term "Mengelicious," eh?

ReplyDeleteIt was on this facebook site that I learnt the fascinating tidbit that the Concertgebouworkest performs Mahler's works from Mengelberg-era scores with Mengelberg's markings. A musician from the orchestra, and facebook member, shared that information...

I was at the concert, and I thought his playing was astonishing. I thought his interpretation of the Bach was brilliant and refined. The depth and complexity of the work carried through. The Dutch audience was incredibly receptive to his playing (which is credit to the Dutch, because Zimmerman did not offer an easy program). I am a classical pianist and am intimately familiar with all the works played, except the Szymanowski. His playing was profound and moving. The last Beethoven sonata is possibly the most difficult sonata in the repertoire, both musically and technically. The depth in the opening fugue and the following theme and variations requires maturity and brilliance. The late music of Beethoven is the voice of God. To express that completely requires incredible artistry and understanding. I felt privileged to watch such a master play this incredible literature.

ReplyDelete