Good collegiate opera companies can draw attention to their work and their students by consciously choosing to stage new and recent operas rather than simply doing the same old chestnuts as professional companies, just with less money and inexperienced singers. The University of Maryland Opera Studio's smart productions are often of great interest because they are the only opportunity to see rare operas on an area stage, things that mainstream opera companies are usually too cowardly to attempt. After an

oh-so-crazy production of Cimarosa's

Il matrimonio segreto last spring, the group has presented an equally "zany" production of an opera I have long wanted to see staged, Conrad Susa's

Transformations. This production was a fitting end to a busy weekend of three operas, after Purcell's

The Fairy Queen at the Folger and Britten's

The Rape of Lucretia at the Châteauville Foundation.

For the 1973 premiere of this opera, American composer

Conrad Susa (b. 1935) worked with poet Anne Sexton to adapt her

book of the same name, the poet's reinterpretation of fairy tales by the Brothers Grimm. Sexton's book is a classic of 60s feminism, a psychological reinterpretation of fairy tales in terms of the poet's own life. The operatic collaboration happened after Sexton had become famous by winning a Pulitzer Prize for her confessional poetry, and just a year before she lost her life-long struggle with mental illness and finally succeeded in killing herself. It is only the first of Susa's several operas (

Black River,

The Love of Don Perlimplín,

The Wise Women, and

Dangerous Liaisons) that I have managed to strike off my list of opera

desideria for new productions.

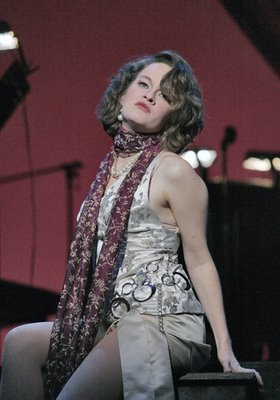

Kara Morgan as Anne Sexton in Transformations, Maryland Opera Studio, 2007, photo by Cory Weaver |

Susa's opera, commissioned by the

Minnesota Opera, uses eight characters including a role that is both Anne Sexton and others, all of whom are patients in a mental hospital. Now it is true that Anne Sexton laced her sometimes acidic poetry with humorous observations, sly references to television, pop culture, the foibles of her own generation. Still, the decision of director Pat Diamond to set the opera in 1973, the year that it was premiered, in a nightclub like Studio 54 seemed more disrespectful than enlightening. None of the official press photos quite capture how over the top it was. By the middle of the second act, the flashing sign ("Club Transformations") and disco ball, the cocktails and pill popping, the white leisure suits, platform shoes, bell-bottoms (costumes by Martha Mann), and groovy hairstyles had become utterly irrelevant.

Fortunately, there was Susa's ingenious score, set for a band, not really an orchestra, of eight players. Susa's music, which I have encountered thus far mostly in his choral pieces, is a skillful combination of dissonance, neo-Baroque tonal and contrapuntal structures, chameleon-like in its mimicry of countless other styles, both forward- and backward-looking.

Transformations references swing, tango, Sousa marches, Broadway, torch songs, to name but a few. Much of the vocal writing is for various combinations of the eight roles, with especially pleasing episodes for the quintet of male voices, in close harmony, often dissonant, performed with skill and grace by Eric Sampson, Nicholas J. Houhoulis, James Biggs, Darren Perry, and VaShawn McIlwain.

However, the opera rests principally on the female roles, especially that of Anne Sexton, sung with dramatic power by the slinky soprano Kara Morgan. In Sexton's poems, various fairy tales are decoded according to sexual episodes from the poet's life, although it is difficult to extricate actual autobiographical content from what may be part of Sexton's narrative persona. The supernatural slumber of Sleeping Beauty is induced by drug addiction, self-medication as a way to cope with her father's molesting of her as a child. Rapunzel, imprisoned in a tower by a possessive old witch, is equated with the old aunt who locks a girl in a study "to keep the boys away." Hansel and Gretel is prefaced by a scene showing a mother pretending to "eat up" her son. Most of the young girl roles are played by the character called Princess, sung with naïveté and vocal strength by soprano Meghan McCall (

reviewed previously in two Opera Bel Cantanti productions). In particular, Morgan and McCall had a beautiful duet in the Rapunzel scene ("A woman who loves another woman is forever young").

University of Maryland Opera Studio will also stage a rare production of Gluck's Armide

this week, from April 19 to 22, with Ryan Brown conducting the musicians of Opera Lafayette in the pit. Ionarts will have a review, of course.

No comments:

Post a Comment