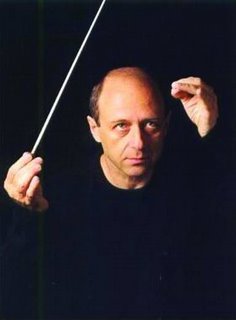

Iván Fischer returned to D.C. for the second of three* times in his first season as Principal Guest Conductor (there are rumors he might become more than that, although my bets and hopes are still on James Conlon) of the National Symphony Orchestra and further displayed his indelible ways with romantic Central European repertoire that orchestras all over the world (have to) play anyway, but don’t always do with the flair and passion a maestro like Mr. Fischer can elicit.

Iván Fischer returned to D.C. for the second of three* times in his first season as Principal Guest Conductor (there are rumors he might become more than that, although my bets and hopes are still on James Conlon) of the National Symphony Orchestra and further displayed his indelible ways with romantic Central European repertoire that orchestras all over the world (have to) play anyway, but don’t always do with the flair and passion a maestro like Mr. Fischer can elicit.Mendelssohn is the composer for this run of concerts (there are repeat performances of this program on Friday 7PM and Saturday 8PM) and this most precocious of composers is represented with two early works to prove it. Symphony No.1, rarely played – but not for lack of beauty – was created when Mendelssohn was 15 years old. A Midsummer Night’s Dream when he was 17 – expanded, seamlessly, from the overture with the incidental music 16 years later, when he was only five years away from his early demise at 38.

Mendelssohn did most everything wrong he could do wrong to be a ‘good’ romantic composer. He was well-mannered, clean, undisturbed, and emotionally balanced. He was financially secure, had no split personality; was neither deaf nor syphilitic. He composed music in a rather classical manner and wasn’t prone to scandals. These deficiencies for the desired romantic stereotype of a composer cannot even be made up by having died sufficiently young. And even that early death is not seen as too tragic (compared to, say, Schubert!) because Mendelssohn’s greatest masterpieces were written when he was still a wee lad (Octet, Midsummer Night’s Dream).

Tim Page, NSO and Ivan Fischer Make The Most of Mendelssohn (Washington Post, February 9) |

The First Symphony enjoyed a happy-go-lucky first movement but never sat firmly in the saddle, either – a deliberate and regal flow in the Andante ensured that the music’s charm came across, but not much more. Perhaps even higher expectations from maestro Fischer contributed to the perception of this performance being curiously lackluster.