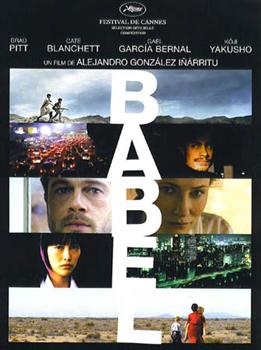

Cate Blanchett and Brad Pitt in Babel, directed by Alejandro González Iñárritu |

Iñárritu's previous two movies were the exceptional Amores Perros and 21 Grams. Babel is considered the third of this trilogy, and indeed, it shares the scope and depth of the previous two. While there is no direct connection between the three films in terms of plot or characters, Iñárritu's films are a complex crossover of experiences, beauty, and an overwhelming sense of grief lying underneath the surface of every scene. (A feeling Naomi Watts had in Grams and seems to carry in EVERY film she touches.) Here Iñárritu has expanded his scope to cover a multinational palette of characters and experiences ranging from the United States to Japan, Morocco, and Mexico. Yet, as far-reaching as the experiences seem environmentally, Iñárritu has found that common sense of humanity and loss in each varied experience.

| Other Reviews: A. O. Scott | David Denby | Financial Times (partial citation in comments) | Washington Post | Rotten Tomatoes |

When a man in the audience stood to ask the cast a question, he decided to address Cate Blanchett. He went on and on for about three minutes about how Blanchett gets better and better in every role. That she only builds on it in this and how much he blah-blah-blahs. (She studied her shoes.) Then, when reminded he was supposed to be asking a question (oh yeah...THAT), he asked how she did it with practically no dialogue. When the host digested all this, he said into the microphone, "The question is..." Without missing a beat, Blanchett jumped on him and said, "No, what he was trying to say is that I'm terrific." And then blushed at the hilarious uproar. It was my favorite part of the night. |

Babel is primarily informed by its deep sense of loss and its characters' desperate desire for those rare moments of joy and transcendence. Iñárritu, himself a buoyant bundle of expressiveness, spoke of his need to speak to something universal after the tragedies of 9/11. Indeed, it is quite fascinating that in all the stories depicted, it is the American couple that seems washed out, grayed, and looking to find some meaning in their marriage and their life after losing a child. Iñárritu orchestrates each of these stories with an overarching sense of dread. Even when the film carries the director's sense of vibrancy (the boys playing, the Mexican wedding, or a girl at a club) one can’t help but feel on edge in these heightened moments of joy.

Babel is receiving some backlash about town, as all films do once the rewards start stacking up, for its overly sprawling narrative as a device or gimmick. Indeed, last year’s Best Picture winner, Crash, has not held up well under critical opinion for that very reason. Certainly, Babel isn’t above such accusations. There is a fourth storyline centered on a Japanese schoolgirl, her relationship to her father, and the loss of her mother. The girl (Rinko Kikuchi) is deaf and is heart-breakingly desirous for someone to see her. These sequences are some of the film's most tragic and beautiful, as Iñárritu envelops us in her muted world and makes us ache with her desperate attempts at connection. Yet, in hindsight, one finds this distant storyline thinly connected to the others. On its own it is strange, disturbing, and beautiful but feels like it is standing alone in juxtaposition to the rest. Yet, I could argue, writer Guillermo Arriaga (also the scribe for Perros and Grams) would like you to connect the fourth simply through feeling.

Babel is receiving some backlash about town, as all films do once the rewards start stacking up, for its overly sprawling narrative as a device or gimmick. Indeed, last year’s Best Picture winner, Crash, has not held up well under critical opinion for that very reason. Certainly, Babel isn’t above such accusations. There is a fourth storyline centered on a Japanese schoolgirl, her relationship to her father, and the loss of her mother. The girl (Rinko Kikuchi) is deaf and is heart-breakingly desirous for someone to see her. These sequences are some of the film's most tragic and beautiful, as Iñárritu envelops us in her muted world and makes us ache with her desperate attempts at connection. Yet, in hindsight, one finds this distant storyline thinly connected to the others. On its own it is strange, disturbing, and beautiful but feels like it is standing alone in juxtaposition to the rest. Yet, I could argue, writer Guillermo Arriaga (also the scribe for Perros and Grams) would like you to connect the fourth simply through feeling.At the post-screening discussion alongside Iñárritu were Kikuchi, Barraza, and the luminous Cate Blanchett. What was most catching, besides that graceful bird, Blanchett, was how the cast listened so attentively to one another, even when they did not speak the same language. All were keenly poised, as if they were trying to decipher the other's mystery simply through digestion of their presence. Once the criticism burns off the top layer of this film what will be left is feeling. A feeling of connectedness through loss and an understanding of ourselves through simple humanity.

No matter what the language.

Panache and a breakdown in communication

ReplyDeleteBy Nigel Andrews

Published: January 17 2007 - FT

There is a scene in Cool Hand Luke that once performed a great service to humanity. Strother Martin, playing a squat, malevolent prison guard with a meanly grandiloquent southern accent, sends rebellious convict Paul Newman sprawling with a punch to the jaw and then says, summing up for the surrounding prisoners: “What we have here is a failure to communicate.”

The line was hilarious at the time (1967). At a stroke the mid-late 20th century’s weariest culture trope, failure of communication, was consigned to derision. But now it pops up again for the 21st century, thanks to Babel, directed by Alejandro González Iñárritu and written by Guillermo Arriaga. This pair made tectonic plates shift in world cinema with Amores Perros, followed by the lesser tremor of 21 Grams. Like those, Babel aims to create a quake with colliding stories, here three initially far-sundered dramas set in Morocco, Japan and California/Mexico.

ADVERTISEMENT

In Morocco, Cate Blanchett is the American tourist struck by a Berber boy’s accidental bullet and tended by desperate husband Brad Pitt in the one-mule local village. In this story we also track the after-traumas in the boy shooter’s family. In Tokyo a deaf-mute girl (Rinko Kikuchi) tries to relate to the world, the flesh (teenage sexuality) and the devil hiding in her family history. In California a Latin nanny hauls her charges off to Mexico, in the parents’ absence, for her son’s wedding. But on the way back there is a nasty border incident provoked by her drunk-driving nephew (Gael García Bernal).

The stories finally link up, sort of. And yes, they are filmed with a panache that puts Babel on a higher level than Crash in the skyscraper of multi-story cinema (whose penthouse is still occupied by Robert Altman, with death a minor detail in his ongoing ascendancy). Yes, too, Arriaga’s script – early at least – brandishes its ideas with a bare, forked ferocity that reminds you this man also wrote The Three Burials of Melquiades Estrada.

Yet Babel soon discloses itself as a movie mortgaged to a single, self-important message. The title says all. Iñárritu and Arriaga invented a fridge sticker – “failure to communicate” – then built the fridge. The American couple in Morocco trying to loudhail their untranslatable distress, the Japanese girl sans speech or hearing, the Hispanics panicking at the patrol point: all tell us, in their chorus of amplified platitude, that in a shrinking world where technology has joined up continents and cultures, People Still Cannot Connect.

It may be true, but it isn’t fresh. It may be food for thought, but it doesn’t feed the imagination. None of these characters is given a history, nor do we believe they have a life outside the projector beam. Babel re-educates us in an old truth, newly urgent in the age of the jet-set co-production. Living movies, not cine-sermons sign-languaged by star-led casts, are what we pay to see at cinemas.

[continued...]