Les Préludes by Liszt opened the London Philharmonic’s WPAS organized performance at the Kennedy Center last Wednesday. If the work is less often heard than its catchy, rousing nature would suggest, it might have to do with the Nazi shadows that still linger over the work, courtesy of having been made a favorite musical tool in Goebbel’s propaganda machine arsenal. As a staunch defender of liberty and freedom – exemplified in his courageous role in the Leipzig ‘Monday-Demonstrations’ during the waning months of the GDR regime – conductor Kurt Masur certainly need not concern himself with such (irrational) attitudes.

Les Préludes by Liszt opened the London Philharmonic’s WPAS organized performance at the Kennedy Center last Wednesday. If the work is less often heard than its catchy, rousing nature would suggest, it might have to do with the Nazi shadows that still linger over the work, courtesy of having been made a favorite musical tool in Goebbel’s propaganda machine arsenal. As a staunch defender of liberty and freedom – exemplified in his courageous role in the Leipzig ‘Monday-Demonstrations’ during the waning months of the GDR regime – conductor Kurt Masur certainly need not concern himself with such (irrational) attitudes.The music is always irresistible, the performance was not quite: A harsh edge on the strings, the strings themselves lost against the brass assaults from behind, and the sound slightly muddled (not all of which can be blamed on the Kennedy Center Concert Hall’s acoustics, although they, to put it mildly, don’t exactly emphasize detail and transparency) contributed to a result that was brooding, dark, and densely woven. A presentation that fit rather well with the idea of hearing Les Préludes over the Volksempfänger on a grim war night.

“Too German, even for German repertoire” is a quip about Maestro Masur who is often seen – especially outside the Anglo-American realm – as a quintessential “Kapellmeister”. That doesn’t mean anything more or worse than “sturdy, solid, reliable, possibly punctilious”. Brahms’ Second Symphony, which very regrettably replaced the planned Bruckner Fourth performance, did not suffer from stodgy, over “German-ness”.

Fast, gentle, but not particularly soft, Masur launched his Orchestra into the Brahms in which the LPO finally achieved sonic distinction and distinctiveness. Separation of orchestral colors was improved over the Liszt or Sibelius Violin Concerto also on the program. With lots of kinetic energy, there was excitement in the boisterous moments. It had neither the natural pace and indelible musicality as a Günter Wand recording offers, nor the polished, creamy sound Karajan elicits – but it managed ample impact, all the same… achieved by the apparent excitement on the part of the (exhausted?) orchestra under the leadership of a chipper, if visibly suffering, much respected conductor. Especially in the fleet beginning of the fourth movement.

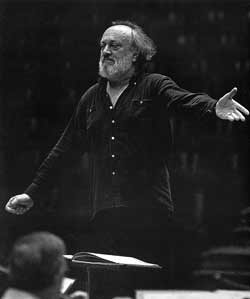

Maestro Masur has long had a most unusual conducting technique in which the limp left arm, seemingly unauthorized, wiggles like a fresh-caught fish. This can be deceiving, because whenever a message needs to be conveyed to the first violins, that arm is right there to tell them what to do: keep going, tune it down, don’t rush. Nowadays his right hand, too, seems to be slipping from the control of his will – and the way it jitters suggests the cruel onset of Parkinsons disease. One wishes to be wrong.

(On the point of Brahms’ Second being performed on Wednesday by a visiting orchestra the night before the NSO starts a series of concerts with the same work it is very surprising that WPAS had no compunctions to let the LPO switch to that particular symphony… fully aware of the resulting conflict. “The Kennedy Center/NSO and WPAS have a very positive working relationship” one is told. Cynics will assume malicious design or crafty negligence rather than innocent coincidence. Whichever it is, Ivan Fischer will have conducted to a couple dozen or hundred fewer listeners as a result.)

Of the five major Romantic violin concertos (Beethoven, Brahms, Bruch, Mendelssohn, Sibelius), it might be the Beethoven that is most difficult to communicate and get ‘just right’ – but it is the Sibelius which stands any chance at all of getting all but the most prodigious violinists sweat before its technical challenges. It is also the least automatically ‘pleasant’ of the five (excellent playing assumed) for it its much more sparse and even stark nature. It is just about impossible not to evoke the idea of a Nordic, cool and even cold, clear sound and consequent reference to the Finish landscape. If that’s a cliché, well, it’s a true cliché.

Of the five major Romantic violin concertos (Beethoven, Brahms, Bruch, Mendelssohn, Sibelius), it might be the Beethoven that is most difficult to communicate and get ‘just right’ – but it is the Sibelius which stands any chance at all of getting all but the most prodigious violinists sweat before its technical challenges. It is also the least automatically ‘pleasant’ of the five (excellent playing assumed) for it its much more sparse and even stark nature. It is just about impossible not to evoke the idea of a Nordic, cool and even cold, clear sound and consequent reference to the Finish landscape. If that’s a cliché, well, it’s a true cliché.Appropriately earthy and dark was the LPO’s support of Sarah Chang’s elegant, silver-threaded performance which explored the corners and abrasive sounds in the concerto more than the (inherently limited) ability to kindle a fire from within. The fierceness of Ms. Chang’s playing is not as impetuous as it was when she was younger (young violin playing ladies are usually among the most aggressive performers), it has – hardly surprising – won a more inward looking quality. But the change is subtle.

Technical prowess was in full display (and needed in this work) but neither coming at the risk of sterility or, for that matter, flawlessness. Ideally this concerto presents a steady cold, blue flame or perhaps of ethereal radiance… in the Masur/LPO/Chang combination there was a little less steadiness in the first movement than I should have liked to hear. Hints of a drive that bordered the hectic, a violin sound that was skinny and uneven. The second movement with its Rheingold-like opening allowed for little or none of the sentiment one might associate with the Adagio (molto, even!) marking. The Karelia Suite resemblance of the (backwards) march of the third movement rang in the most satisfying playing on everyone’s part: A wonderful balance between the relaxed (Orchestra) and the fiercely forward oriented (Chang) made for a study in contrast and an example of cohesion in one. Only to the very end did that harmony seem to come apart.

Much to take away from particular moments of this concert then, even if the whole was distinctively underwhelming.