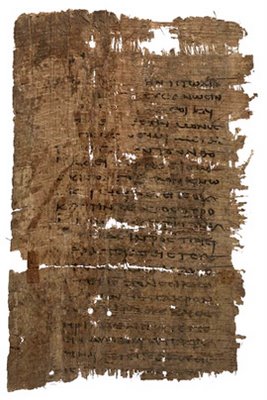

Logia Jesou, Oxford, Bodleian Library, MS. Gr. th. e. 7 (P), 3rd century CE |

The Bible has changed so much over the centuries, in language, in content, in the way it was copied and transmitted, in how people interacted with it. The show begins with some of the oldest fragments, Egyptian papyrus bits from around the year 200, like the Egerton Gospel and the Chester Beatty papyri. The pages in the first few rooms, in mysteriously dim light, are mostly devoid of visual imagery and, on the surface, may not be of great interest for visitors who do not read Greek, Latin, Hebrew, Arabic, Syriac, Armenian, Ethiopian, and Coptic. For this reason, the informative and well-produced audio tour is certainly worth your $5, especially since the exhibit itself is free. It adds some much-needed context about the significance of the pieces on display, for example, explaining the importance of the Nag Hammadi Codex II and related fragments, now known to contain portions of the so-called Gospel of Thomas, and the Codex Sinaiticus.

Greater artistic interest is found in the later rooms, which include manuscripts from early Christian Europe. The most important is the Rabbula Gospels, a striking and lavishly illuminated manuscript made in 586 at the monastery of Saint John in Beth Zagba, Syria (now owned by the Biblioteca Laurenziana in Florence). It is one of the best surviving examples of early Christian painting, which you may remember from your art history textbook. Of equal historical importance is the so-called Alcuin Bible, produced at the monastery of St. Martin in Tours under the direction of Alcuin of York, in the reformed lettering known as Carolingian minuscule, to be presented to Charlemagne. From around the same period is an exquisite carved codex cover, the Douce Ivory from the Bodleian Library, made at Aachen, the capital of Charlemagne's empire, around the year 800. If you are not able to go to this exhibit in person, the Sackler Gallery has made a particularly good online exhibition, which includes short audio-video clips that explain the various parts of the show.

At the same time, pages from the latest example of a fully handwritten and lavishly illustrated copy of the Bible, the Saint John's Bible, are on display at the Library of Congress as Illuminating the Word: The Saint John's Bible (open until December 23). As I described in a post earlier this fall (Remembering the Codex, October 16), calligrapher Donald Jackson dreamed up this quixotic project, to create a modern manuscript of the Bible, copied entirely by hand on vellum using traditional materials. He convinced the monks of St. John's Abbey, the Benedictine house that runs St. John's University in Collegeville, Minn., to fund his dream. Once again, for only the most recent time in its 1,500-year history, the Order of Saint Benedict demonstrates its devotion to the preservation of learning.

At the same time, pages from the latest example of a fully handwritten and lavishly illustrated copy of the Bible, the Saint John's Bible, are on display at the Library of Congress as Illuminating the Word: The Saint John's Bible (open until December 23). As I described in a post earlier this fall (Remembering the Codex, October 16), calligrapher Donald Jackson dreamed up this quixotic project, to create a modern manuscript of the Bible, copied entirely by hand on vellum using traditional materials. He convinced the monks of St. John's Abbey, the Benedictine house that runs St. John's University in Collegeville, Minn., to fund his dream. Once again, for only the most recent time in its 1,500-year history, the Order of Saint Benedict demonstrates its devotion to the preservation of learning.The English text, taken from the NRSV translation, does not look medieval, although the script that Jackson developed is based on older lettering. Although the St. John's Bible is a Catholic book, the illuminations draw from other religious traditions and modern sources. In striving to be universal, however, Jackson and his team have made something neither fish nor fowl. Art history creeps in with an ox from the walls of the Lascaux cave in the Nativity illumination; science manuals make an appearance in the illuminations of butterflies and other insects; the Tree of Jesse, illustrating the genealogy of Jesus, morphs into a menorah. It is a modern and universal work (that quality of being all things and therefore no one of those things), built on a medieval foundation.

The Library of Congress has put together a small companion exhibit from its own collection of Bibles, in a couple small cases at the end of the exhibit. The manuscript tradition is represented by a tiny Latin Bible made in England in the 13th century and a 15th-century codex from Venice. For the final stage of the Bible's evolution, from the individualized and handwritten to the uniform and printed, there is a rare exemplar of the King James Bible (1611) and the Eliot Indian Bible (1663), the first Bible printed in America. With the Saint John's Bible's return to a manuscript form, albeit with a standardized text, the circle is complete.

No comments:

Post a Comment