| Available at Amazon: Don Quixote, new translation by Edith Grossman (released on October 21, 2003) Don Quixote (online version, English translation) Don Quijote (online version, Spanish original) Ruta de Don Quijote (pilgrimage route following Don Quixote around Spain) Don Quijote de La Mancha: Romances y Músicas, Montserrat Figueras, Hespèrion XXI, La Capella Reial de Catalunya, Jordi Savall (released on January 10, 2006) |

Part 5 | Part 6 | Part 7 | Part 8

Setting out from the Duke and Duchess, Don Quixote and his squire make their way to Barcelona. As all travelers at that time, they had to contend with the bands of brigands on the roads in and out of the city. They fall in with a thief with a heart of gold, Roque Guinart, who happens to have read the first part of Cervantes's novel. He stages a magnificent entrance for the knight into Barcelona, where he is greeted by

the sound of a multitude of hornpipes, kettledrums, the jingling of bells, and shouts of "Clear the way, clear the way!," apparently coming from the direction of the city. Don Quixote and Sancho, looking all around them, saw the sea, which they had never before that day behold. They saw the gallies on the beach, resounding with clarions, trumpets, and hornpipes, which filled the air for many leagues around with sweet and martial accents. (Chapter 61)Savall's recording gives us two instrumental selections to convey the hustle and bustle of the city. When Don Quixote is fêted in the home of his host, Don Antonio, a number of young girls play a trick on the knight by asking to dance fast dances with him, until he has to retire to his room, exhausted. To represent this wild dancing, Savall records a catchy song called Un sarao de la chacona, by Catalonian composer Joan Arañés.

It is in Barcelona that Don Quixote finally meets his match, in the person of the Knight of the White Moon. The latter is none other than the knight's friend from the village, Sansón Carrasco, trying again to force Don Quixote to return home. This time Sansón is prepared, and he knocks Don Quixote from his horse, a defeat that forces Don Quixote to accept the terms imposed by his opponent, that he return home and give up his arms for the period of one year. Since much of the second part of Don Quixote is devoted to the tricks played on the knight by readers of the first part, it is hardly surprising that the knight's host in Barcelona is disappointed to lose his famous guest:

"My dear sir," exclaimed Don Antonio, "may God forgive you for the wrong you have done the world by seeking to deprive it of its most charming madman! Do you not see that the benefit accomplished by restoring Don Quixote to his senses can never equal the pleasure which others derive from his vagaries? But it is my opinion that all the trouble to which the Señor Bachelor has put himself will not suffice to cure a man who is so hopelessly insane; and if it were not uncharitable, I would say let Don Quixote never be cured, since with his return to health we lose not only his drolleries but also those of his squire, Sancho Panza, for either of the two is capable of turning melancholy itself into joy and merriment." (Chapter 65)In other words, Spain is more interesting with Don Quixote wandering around in it. As shown by the centennial celebrations last year, that is still true 400 years later. However, even when defeated, the knight hit upon another crazy plan, suggesting that he and Sancho Panza should become shepherds and live out the Arcadian life in the fields. This is a clever literary diversion on the part of Cervantes, who manages in the last few pages of the book to take aim at a genre related to the fantasy epic he has skewered in Don Quixote.

Stories about monarchs or other powerful figures living as shepherds were not uncommon -- the best example is Torquato Tasso's Aminta (published in Italian in 1581). That the idea appealed to crowned heads is evident, for example, in the fact that Pietro Metastasio wrote a libretto in 1751 based on Aminta, for a private performance to celebrate the birthday of the Empress Maria Theresa at Schönbrunn Palace, in which her children played the leading roles. The libretto or other forms of the story were popular with opera composers, too, such as Mozart who used an adaptation of Metastasio's libretto in his opera Il Rè Pastore. Once again, Cervantes uses the ingenious knight's folly to satirize an entire genre. The discussion of the pleasures of the pastoral life is priceless:

"God bless me!" cried Don Quixote, "what a life we are going to lead, Sancho, my friend! What music we shall hear -- the strains of reed flutes, Zamora bagpipes, tabors, timbrels, rebecs! And if amid all these different varieties of music the albogues also resound, then practically all the pastoral instruments will be there."

"What are albogues?" inquired Sancho. "I never heard tell of them, nor have I seen one in all my life."

"Albogues," replied Don Quixote, "are plates resembling brass candlesticks, which when struck together on the empty or hollow side, make a noise that, if not very agreeable or harmonious, is still not displeasing to the ear and goes well with the rustic character of the bagpipe and tabor." (Chapter 67)

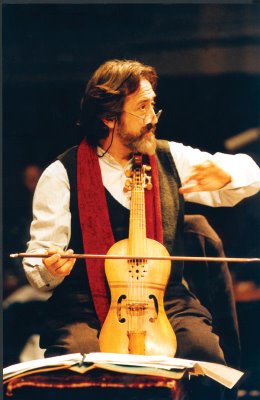

Jordi Savall |

Cervantes ultimately decided that the only way to end the story -- and to prevent other spurious sequels, the first of which he mercilessly attacks twice more in the final pages of the second part -- was with the death of Don Quixote. However, rather than have him killed in an adventure, something that could have easily happened given Don Quixote's foolhardiness, he falls ill. As a result of a bad fever, he comes to his senses on his sickbed and atones for all the things he has done. Cervantes does not mention any music that accompanies Don Quixote's death or funeral, but Savall does something quite beautiful by creating in the final section of this excellent recording the funeral service that he should have had. We hear an anonymous Lacrimosa setting (from the Requiem Mass) and two selections from the greatest Spanish composer of the first half of the 16th century, Cristóbal de Morales. (He is surpassed in Spain only by Victoria, whose compositions are closer in date to the publication of Don Quixote.) An organ arrangement of a chant from Holy Week, Circumdederunt me (They have surrounded me), connects Don Quixote's suffering with that of Christ. The final track is the Pie Jesu movement from Morales's exquisite setting of the Requiem Mass. May Don Quixote rest in peace.

In spite of its steep cost (around $50 for 2 CDs, although I have seen it as low as $39.99), I obviously find this recording both fascinating as an intellectual idea as well as lovely listening. It is packaged to look more like a book than a CD, an extensive book with texts and notes in Spanish and Catalan, as well as full translations in French, English, German, Italian, and Japanese. (The CDs are in front and back pockets.) For anyone setting out to read Don Quixote for the first time, or looking to revisit it, listening to this fascinating recording adds a remarkable new dimension to the masterpiece of Cervantes, one that the words alone cannot communicate.

Great write up.

ReplyDeleteThanks, Cube.

ReplyDeleteIt's in the SACD format (and not available otherwise), which contributes a little to the steep price tag.

ReplyDeleteAh, yes, I should have mentioned that...

ReplyDelete