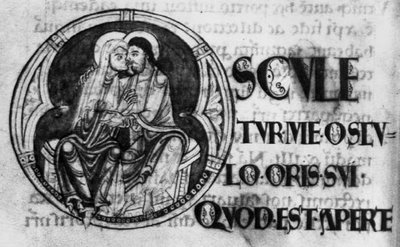

Cambridge, King's College, MS 19, f. 12v (from St. Alban's, 12th century), verse 1 of the Song of Songs, image scanned by Prof. E. Ann Matter |

In this historical context, I see no reason to suspect that Giovanni da Palestrina's polyphonic motet cycle drawn from the Song of Songs is somehow secretly a secular work. In this new recording's liner notes, Vincenzo Soravia (translation by Susan Marie Praeder) only suggests this by mentioning that Palestrina had married his second wife in 1581, after surviving a tragic period in his life in the previous decade. For his fourth book of published motets (Motettorum liber quartus ex Canticis canticorum, 1583-84), Palestrina selected just under half of the book's verses, arranged into 29 motets, set to music of almost uniform length (on this recording, all of the tracks last around two minutes). Indeed, in his dedication of the publication, addressed to Pope Gregory XIII, Palestrina publicly regretted that he had in his youth devoted a small part of his creative energy to the composition of secular madrigals.

| Available at Amazon: Giovanni da Palestrina, Canticum Canticorum, Capella Dvcale Venetia, Livio Picotti (released on June 20, 2006) |

What distinguishes this new recording is the performance practice. Director Livio Picotti had the six singers of his Capella Dvcale Venetia -- five men and one woman, who are in various arrangements, since all of these motets are for five voices -- sing one on a part, accompanied by an improvised basso continuo, realized by two players, on a lute (or theorbo) and an organ. This invented part is derived from Palestrina's bass line: when the composer reduces the texture to only upper voices, it disappears. The instrumental part is discreetly rendered, never obtrusive, a gentle support for the voices. We know that Victoria actually composed some continuo parts for his polyphonic works, but mostly in the last ten or fifteen years of his life, after Palestrina was dead. I am not aware that Palestrina himself ever actually used the continuo directly (which does not mean there may not be evidence of it), but it makes a lovely sound in this unusual performance. Picotti's intention may have been to make Palestrina's sacred music sound more like the vocal chamber music of the stile moderno. It is an experiment well worth hearing.

cpo 777 142-2

No comments:

Post a Comment