I may still not be convinced that La Clemenza is as great an opera as some of its supporters wish to make it out to be, but I must admit it is growing on me. So much right off the bat: Had I seen the Salzburg production and consequently some of the possibilities in how to present this story with at least some degree of credibility and believability before last May, I would not have been quite as forgiving to the Washington National Opera’s production which, in contrast, never bothered to go through the trouble of trying to do the same and contented itself with letting La Clemenza helplessly slide into the ridiculous; with audiences laughing outright at story and production. No one was laughing at the Salzburg performance, be assured – and not just because the high-society types in attendance at the Felsenreitschule are such dour snobs.

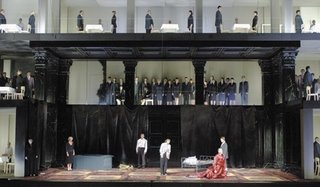

Staged in a three level industrial concrete building stretching the width of the wide stage, only the royal quarters at the centre of the lowest level are set off from the rough-hewn look of the set. The tier structure allows not only for some visually arresting shots of the singers but also for subtler points about story and plot to be made – such as the conspiring and going-ons that surround, but never involve Titus, who sits or lies alone on his bed. When the chorus first enters, it does as a horde of photographing and gawking tourists. Amidst all, at the center of all the action, Titus is yet alone, isolated, prisoner of his fame and status; an animal exhibited and for all his omnipotence: powerless.

W.A.Mozart, La Clemenza di Tito, Mackerras / Scottish CO Trost, Martinpelto, Kožená DG     |

Compare to that the fake, stilted, awkward Drottningholm production where La Clemenza is stomped back into a period piece full of costumes, fake smiles, women in unflattering trouser costumes that make them look like, well… women in trousers or, worst of all, in Maria Höglind’s case, a fat cow that she really isn’t. The chorus is an assortment of brown-faced tributaries to Tito... replete with Leopard Skins, Palms, Gold, Myrtle – the entire cliché-ridden treasure chamber on their arms and clad in every equally clichéd costume that might have found its way out of a 1970’s B-movie about Sinbad and the Seven Seas. I don't believe that Anita Soldh's mannered, cold, superficially involved Vitellia could motivate any man with a spine even to open the door for her, much less murder a best friend. Pretty Pia-Marie Nilsson is similarly hampered by the direction and the costume but likeable. This production also makes visible the qualities that might go unnoticed in the Salzburg version seen on its own: Namely that direction is most important for the moments in which a singer does not sing. On the small Drottningholm stage, there is lots of meaningful looking and head-nodding and shaking, small meaningful hand gestures, a few, tiny anticipatory steps forward or backward. (Wide-eyed Lani Poulson’s Sesto, always and ever so moved, overjoyed, distraught, remorseful is the worst offender.) All in all: The kind of behaving that makes the “acting” in Opera wooden and unnatural. Those who think that ignoring the theatrical aspects of opera is the calling card of a true Opera aficionado and voice-snob will be delighted: Such beautiful glittering costumes, such amply applied rouge on those cheeks.

Poulson’s portrayal of Sesto coupled with the stilted, beautiful but completely unattractive, cartoonish Vitellia (part Queen of the Night, part Marshallin) of Ms. Soldh alone are enough to drive me far away from this production. Poulson undermines Sesto’s every emotion with feeble, overdone 'acting' and ill judged accentuations. With Kasarova, we accept that she is determined to do whatever it takes to get with Vitellia. When her Sesto stops to regret, the viewer is relieved for a brief moment. When she continues, we are not surprised. But when the Drottningholm Sesto pretends to be on evil’s foot, it seems laughable – the relapse to moral concern ridiculous. Meanwhile, the smiles of Höglind’s are maddening in their sugary artificiality. Like Poulson she turns her character into an effeminate, sappy naïf. Her Kušej-Harnoncourt pendant, Aline Garanča, does exactly the opposite. Although also a beautiful woman with soft facial features, her long face and its laconic expression (it rarely ever changes from its somber look and ‘sits’ on her like a mask, in great contrast to Kasarova, where every emotion grinds and moves her face, brows, jaw), she, too, makes her character a believable young man of stern conviction.

Poulson’s portrayal of Sesto coupled with the stilted, beautiful but completely unattractive, cartoonish Vitellia (part Queen of the Night, part Marshallin) of Ms. Soldh alone are enough to drive me far away from this production. Poulson undermines Sesto’s every emotion with feeble, overdone 'acting' and ill judged accentuations. With Kasarova, we accept that she is determined to do whatever it takes to get with Vitellia. When her Sesto stops to regret, the viewer is relieved for a brief moment. When she continues, we are not surprised. But when the Drottningholm Sesto pretends to be on evil’s foot, it seems laughable – the relapse to moral concern ridiculous. Meanwhile, the smiles of Höglind’s are maddening in their sugary artificiality. Like Poulson she turns her character into an effeminate, sappy naïf. Her Kušej-Harnoncourt pendant, Aline Garanča, does exactly the opposite. Although also a beautiful woman with soft facial features, her long face and its laconic expression (it rarely ever changes from its somber look and ‘sits’ on her like a mask, in great contrast to Kasarova, where every emotion grinds and moves her face, brows, jaw), she, too, makes her character a believable young man of stern conviction.I have slight difficulties with Schade’s (whose singing I admire) characterization of Titus – although that character is admittedly hard to pull off for any singer/actor – being on a relentless forgiving-spree and deciding to marry three different women in one day as he is or does. Compared to Stefan Dahlberg’s picture perfect little prince in ermine and purple coats, however, Schade is brimming with life and realism. Still: Less neurotic, modestly more composed, not as much ‘acted’ and I’d find the character much more appealing. Dahlberg’s singing is good, Schade’s better.

The Chorus and Orchestra of the Drottningholm Court Theatre under the Mozart Veteran Arnold Östman know how to do ‘HIPerformances’ of Wolfgang Amadeus’ operas and have recorded much admired versions of the Da Ponte operas and especially the Magic Flute for Decca. With original instruments but also costumes and wigs (!!) (this performance was originally recorded for Television and the musicians are very visible in this small theatre) they turn in a fine, not always secure, very fast performance with some arias taken at speeds that first appear implausible. Harnoncourt’s Vienna Philharmonic is of course not a period instrument band, emits a mightier sound (necessary for the larger space) but can be light-footed just the same which is not surprising since arguably no great modern orchestra has more Mozart in their blood, than the Viennese. Harnoncourt’s undogmatic understanding of period performance surely helps, too. He allows for a more relaxed reading than Östman which supports the beautiful arias and duets to really shine.

The singing, meanwhile, if it still mattered for me, is very fine on the Östman performance – with Poulson as the stand out and the restrained, noble Dahlberg in good form. The Orchestra plays well and fleet, but is no match for the recordings on CD (Hogwood and presumably Jacobs if you want period instruments, Mackerras - my favorite recording - if you will take either). The Harnoncourt cast has not only two great actors but also two great singers in the main roles: Röschmann is radiant, Kasarova better still, with her characterful, strong voice. Schade’s Tito doesn’t need my praise; he’s carved that role out of the repertoire for himself… only at times do I sense a little strain and push that betrays that this isn’t quite so easy to sing, after all. Servilia in Salzburg is none other than Barbara Bonney, a very mature lass, to be sure, but vocally assured. She looks a bit like an intrusion into the cast; a different kind of actor and singer... but like an upper-class American tourist on Lago Como, she fits in just fine after a while and is generally welcomed.

The singing, meanwhile, if it still mattered for me, is very fine on the Östman performance – with Poulson as the stand out and the restrained, noble Dahlberg in good form. The Orchestra plays well and fleet, but is no match for the recordings on CD (Hogwood and presumably Jacobs if you want period instruments, Mackerras - my favorite recording - if you will take either). The Harnoncourt cast has not only two great actors but also two great singers in the main roles: Röschmann is radiant, Kasarova better still, with her characterful, strong voice. Schade’s Tito doesn’t need my praise; he’s carved that role out of the repertoire for himself… only at times do I sense a little strain and push that betrays that this isn’t quite so easy to sing, after all. Servilia in Salzburg is none other than Barbara Bonney, a very mature lass, to be sure, but vocally assured. She looks a bit like an intrusion into the cast; a different kind of actor and singer... but like an upper-class American tourist on Lago Como, she fits in just fine after a while and is generally welcomed.Recorded live for Television (they show things like Clemenza on Swedish Television, believe it or not), the production is obviously not as meticulously thought out as the one Brian Large directed for release on DVD. There are understandably no fireworks or billowing clouds of smoke when the Capitol is set ablaze (in Drottningholm there are a few bleached-out orange projections cast on the painted backdrop – in Salzburg the chorus is forced to the edge of the three-tier construction by a truly threatening smoke) and there are some - albeit judicious - cuts that make (together with the faster tempi) the performance almost half an hour shorter. The quickness does not redeem this performance, the bredth and length does not harm the Salzburg performance.

It is the Salzburg production that shows the possibilities of reviving an opera like La Clemenza, making it meaningful and riveting, despite its inherent weaknesses. Bravo. The Drottningholm production, however, for all its beauty of playing and singing, only goes to show why the opera fell out of favor in the first place.

The correct Italian would be, I think, "La Clemenza dei Titi"...

ReplyDelete