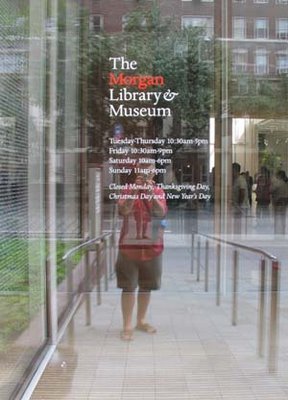

I was in New York this weekend, witnessing a beautiful wedding in Brooklyn on Sunday morning -- Guy and Luisa: mazeltov! -- and we spent Saturday being cultural tourists. I went first to see the addition that Renzo Piano designed for one of my favorite institutions, the Pierpont Morgan Library at Madison Avenue and 36th. It was Paul Goldberger's brilliant article (Molto Piano, May 29) in The New Yorker that first got me interested in the new space, although Nicolai Ourossoff had written about it in the previous month (Renzo Piano's Expansion of the Morgan Library Transforms a World of Robber Barons and Scholars, April 10) in the New York Times. My first impression of the new façade -- Piano's design shifts the entrance to Madison Avenue, which increases the museum's street presence -- was that it was dull and industrial. Plain grey steel plates deaden most of the elevation, rhyming with the stone of the neoclassical building on the corner, and grates and other metal pieces jut out in the sort of "unfinished" look of Piano's most famous building, the Centre Pompidou, designed with Richard Rogers.

I was in New York this weekend, witnessing a beautiful wedding in Brooklyn on Sunday morning -- Guy and Luisa: mazeltov! -- and we spent Saturday being cultural tourists. I went first to see the addition that Renzo Piano designed for one of my favorite institutions, the Pierpont Morgan Library at Madison Avenue and 36th. It was Paul Goldberger's brilliant article (Molto Piano, May 29) in The New Yorker that first got me interested in the new space, although Nicolai Ourossoff had written about it in the previous month (Renzo Piano's Expansion of the Morgan Library Transforms a World of Robber Barons and Scholars, April 10) in the New York Times. My first impression of the new façade -- Piano's design shifts the entrance to Madison Avenue, which increases the museum's street presence -- was that it was dull and industrial. Plain grey steel plates deaden most of the elevation, rhyming with the stone of the neoclassical building on the corner, and grates and other metal pieces jut out in the sort of "unfinished" look of Piano's most famous building, the Centre Pompidou, designed with Richard Rogers.However, once you go in that rather bland entrance, the interior space that Piano has created is a marvel of light and airiness. The presence of a museum cafe tends to make this high-ceilinged volume into a noisy echo chamber, but the vastness has a pleasant emptiness to it, a void mostly without function, joining the three buildings of the Morgan campus and framing views of the surrounding buildings and, that rare commodity in Manhattan, glimpses of sky. Digging far down into the ground, Piano put most of the details of the commission -- storage space, a rather large concert auditorium -- completely out of sight. Judging by the performers who were on the schedule earlier this spring, the Morgan will be hosting a world-class series of concerts in its basement.

|  |  |

By way of seconding Mark's comments about the importance of etching and printmaking, there is a small but excellent exhibit of etchings and drypoints by Rembrandt at the Morgan Library, Celebrating Rembrandt: Etchings from the Morgan, continuing through October 1. (It is so small that it shares a room with a less important but lovely companion exhibit, From Rembrandt to van Gogh: Dutch Drawings from the Morgan.) In addition to some beautiful landscapes by the Dutch master, whose 400th birthday we celebrate this year, and examples of many of his best religious engravings, I was struck by the two handfuls of tiny self-portrait images. Rembrandt left behind an impressive number of self-portraits, works that never cease to impress me for their probing introspection. The rare self-portrait with Saskia (shown here) is particularly noteworthy: in it Rembrandt appears young, strong, self-confident. Others in the show preserve odd and often humorous expressions.

The best pieces in this exhibit are the engravings on commonplace subjects, rendered sometimes with fervent sympathy, as in the Beggar Man and Woman Behind a Bank (c. 1630), a subject that must have created an interesting resonance in the heart of the collector, one of the richest men in the world at the time. These sorts of views, a series not actually intended to be a series, were inspired by the incisive engravings of Jacques Callot, who had actually lived in the Netherlands in the late 1620s. Rembrandt was an avid collector of his work. In other cases, a razor-sharp wit comes through, as in the absolutely hilarious The Monk in the Cornfield, an anti-clerical poke in the rib depicting a monk beating the barley with a milkmaid in a field.

The best pieces in this exhibit are the engravings on commonplace subjects, rendered sometimes with fervent sympathy, as in the Beggar Man and Woman Behind a Bank (c. 1630), a subject that must have created an interesting resonance in the heart of the collector, one of the richest men in the world at the time. These sorts of views, a series not actually intended to be a series, were inspired by the incisive engravings of Jacques Callot, who had actually lived in the Netherlands in the late 1620s. Rembrandt was an avid collector of his work. In other cases, a razor-sharp wit comes through, as in the absolutely hilarious The Monk in the Cornfield, an anti-clerical poke in the rib depicting a monk beating the barley with a milkmaid in a field.Even better than the Rembrandt is the double exhibit occupying the new exhibit space designed by Piano, the Engelhard Gallery, over part of the atrium. On one side is a selection of the best literary manuscripts in the Morgan Library collection. I stood in shock over many of the cases, looking at the handwriting of so many heroes: Thoreau's journal, open to a page describing himself unsuccessfully chasing a loon on Walden Pond; the notebooks of the Brontë sisters, often in impossibly small script; Lord Byron's autograph copy of Don Juan. Most remarkably, I admired Jean-Jacques Rousseau's autograph copy of his novel, Julie ou La nouvelle Héloïse, one of the great epistolary novels of the 18th century. A manuscript in the hand of Galileo, supposedly explaining calculations of the orbits of Jupiter's moons, is interesting but completely inscrutable to me.

Of perhaps greater interest for Ionarts readers is the exhibit of stunning manuscripts of music, mostly in the hands of composers, which shares the Engelhard Gallery through October 1. Treasure after treasure is there for your perusal, behind glass of course, from Schubert's Winterreise and the slow movement from the Death and the Maiden quartet to Schumann's Frauenliebe und Leben, Schoenberg's Gurrelieder, Beethoven's tenth violin sonata and D major piano trio, Strauss's Don Juan, Mozart's Haffner Symphony, and Duparc's L'Invitation au Voyage. Just as an author's handwriting is the most direct way to grasp his personality (after he is dead, that is), a composer's musical script is telling. No handwriting analysis here, please, but I never feel closer to historical music than I do when working with primary sources.

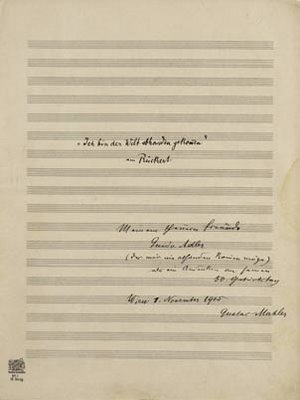

The best part about this exhibit is that there are four listening stations, where up to two people at a time can listen to the excerpt of music featured on a corresponding manuscript page, as with Chopin's A-flat polonaise, op. 53. The first of these that I tried was Thomas Hampson's heart-rending performance of Mahler's song Ich bin der Welt abhanden gekommen, from the Rückert-Lieder. Sotheby's auctioned off the rediscovered manuscript copy of the completed song in 2004, a score that Mahler gave to his friend, the Viennese musicologist Guido Adler (title page shown at right). The Morgan Library owns a set of three of Mahler's autograph sketches for this song, which was a source of material for the Adagietto of Mahler's fifth symphony. (They also own a manuscript of the symphony, which is actually shown in the exhibit, but open to a different movement.)

The best part about this exhibit is that there are four listening stations, where up to two people at a time can listen to the excerpt of music featured on a corresponding manuscript page, as with Chopin's A-flat polonaise, op. 53. The first of these that I tried was Thomas Hampson's heart-rending performance of Mahler's song Ich bin der Welt abhanden gekommen, from the Rückert-Lieder. Sotheby's auctioned off the rediscovered manuscript copy of the completed song in 2004, a score that Mahler gave to his friend, the Viennese musicologist Guido Adler (title page shown at right). The Morgan Library owns a set of three of Mahler's autograph sketches for this song, which was a source of material for the Adagietto of Mahler's fifth symphony. (They also own a manuscript of the symphony, which is actually shown in the exhibit, but open to a different movement.)I probably do not have to tell you that the words of this song meant something very profound and personal to Mahler ("I am dead to the world's tumult, / And I rest in a quiet realm!"), and so seeing the composer's early attempts to put the song to paper, coupled with hearing the music, was emotionally overwhelming. It was not the only score in front of which I trembled, as right next to the Mahler song is shown Massenet's autograph score of Manon, open to the wistful duet En fermant les yeux from Act II. Des Grieux relates his dream of marrying Manon, moving to a snug white maisonnette in the country, but little does he realize that she has just sung farewell to their petite table and will soon run out the door into the arms of another man. The words of the libretto are so sugary, but the music makes them devastatingly sincere: the soft lilting of the strings and the broad leaps of the tenor part (sung in the Morgan Library's excerpt by Roberto Alagna), its poignant appoggiature and sudden flights into sweet, high, head voice. It's so boyish and idealistic, which makes the blindness of Des Grieux to the true character of the shallow Manon all the more tragic.

Looking forward to the Rembrandts'. Your correct about the new addition. It seems wasteful from the street, but it dose bring lots of light to the center. It's less stogie.

ReplyDeleteMark, enjoy the Rembrandt on your next NY trip.

ReplyDelete