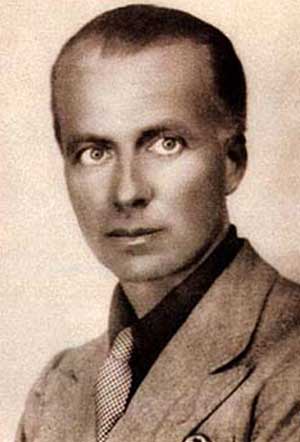

Alex Ross wrote an article (Giacinto Scelsi, The Messenger, November 21, 2005) on the string quartets of eccentric Italian playboy composer Count Giacinto Scelsi in The New Yorker last fall, with some added notes at The Rest Is Noise. Scelsi's 100th birthday would have been last year (he died in 1988), and an unscientific search indicates that a bewildering number of recordings dedicated to his music have been made (although Alex says that many of them are technically out of print). Scelsi's sister, who runs a foundation (Fondazione Isabella Scelsi) dedicated to her brother's musical legacy and maintains his house in Rome as a museum, organized a Scelsi festival in Rome, which just concluded in May. This is a situation that would have surprised no one more than Giacinto Scelsi himself.

Alex Ross wrote an article (Giacinto Scelsi, The Messenger, November 21, 2005) on the string quartets of eccentric Italian playboy composer Count Giacinto Scelsi in The New Yorker last fall, with some added notes at The Rest Is Noise. Scelsi's 100th birthday would have been last year (he died in 1988), and an unscientific search indicates that a bewildering number of recordings dedicated to his music have been made (although Alex says that many of them are technically out of print). Scelsi's sister, who runs a foundation (Fondazione Isabella Scelsi) dedicated to her brother's musical legacy and maintains his house in Rome as a museum, organized a Scelsi festival in Rome, which just concluded in May. This is a situation that would have surprised no one more than Giacinto Scelsi himself.As I understand it (I am no expert), Scelsi never received serious musical training, although he could apparently read and write musical notation. As the work of an enlightened amateur, most of his compositions were essentially improvised and then notated in one form or another by Vieri Tosatti, a composer with greater technical skills, who later claimed to be more the composer of Scelsi's works than Scelsi. In the very brief article on Scelsi in the 1980 New Grove, Claudio Annibaldi puts it this way:

Since music is, for Scelsi, an intuitive link with the transcendental and involves the annulment of creative individuality, the countless changes of style contributing to the non-professional features of his vast output embody a spiritual process substantially unchanging. [...] Generally adopting a free atonality, he employed styles ranging from the modish 'machine music' of the 1920s [to neo-Romanticism and embryonic serialism].Franco Sciannameo, former violinist of the Quartetto di Nuova Musica and faculty member at Carnegie Mellon University, wrote an article remembering his work with Count Scelsi (A personal memoir: Remembering Scelsi, Summer 2001) for The Musical Times, in which he states that the Quartetto's work preparing Scelsi's quartets for performance was supervised by both Scelsi and Tosatti. He recounts an anecdote that says a lot about Scelsi's personality and about his importance for other composers:

In the meantime, a string quartet from Hamburg gave a concert in Rome at the Goethe Institute. Its programme included Scelsi’s Quartetto no. 2. We were invited to attend the concert, at which the Hamburg players performed honourably, and at the end of Scelsi’s piece the first violinist invited the composer, who was present in the hall, to stand and take a bow. An upset Scelsi, though, moved rapidly to front stage and in a stentorian yet agitated tone of voice declared that the instrumentalists’ interpretation did not correspond to his wishes; therefore he could not acknowledge the audience’s applause.We could compare Scelsi's role in modern music to that of Henri Rousseau in modern painting (see my review of the Paris retrospective of Rousseau's works from this spring, a show that just opened at the National Gallery of Art here in Washington). Both were dilettantes, in the noblest sense of that word; both approached their work with the most deeply felt sincerity, in the face of occasional scorn from the official representatives of their disciplines; and both were embraced by radical artists/composers of their time, because their style, arrived at by the accident of an intensely personal but somewhat haphazard artistic process, coincided with the thornier avant-garde tendencies of more learned artists/composers. Rousseau, like Scelsi, was both messenger, as Alex put it -- the one who brings by instinct what is in the work of others an artistic construct -- and buffoon, the fool whose foolishness should be heeded.

The German foursome must have not understood Italian or the absurdity of Scelsi’s declaration, because one hour later they were the guests of honour at a reception held in Scelsi’s home. Elliott Carter was among the guests that evening, and upon learning that the Quartetto di Nuova Musica was working on Scelsi’s latest quartet, he said that some day he would hope that his two quartets (it was 1965) would be performed together with Scelsi’s, so fond was he of Scelsi’s music. Mr Carter then added that Darius Milhaud also held Scelsi in high esteem.

| Available at Amazon: Giacinto Scelsi, Natura Renovatur and other works, Frances-Marie Uitti, cello, Münchener Kammerorchester, Christoph Poppen (released on June 27, 2006) |

The cello pieces include two works from the set of Three Latin Prayers for Solo Voice, transcribed for cello, Ave Maria and Alleluja. If anyone knows Scelsi's music for this instrument it is Ms. Uitti, who worked closely with the composer for much of her life. In her contribution to the liner notes, she confesses that Scelsi was "to become my musical mentor, advisor in spiritual practices and, in the end, a friend." I believe this may make Uitti the Grand High Abbess of Scelsianity. Indeed, she is very close to Scelsi's sister and is the only person who has gone through all of the surviving tape recordings that the composer made of his improvised "messages from beyond." (See her essay about the experience, Preserving the Scelsi Improvisations, in Tempo in October 1995.) If anyone could do justice to such a transposition, from voice to cello, it is she. The performances are lovely and oh-so-mysterious, especially on the work actually written for the instrument and dedicated to Ms. Uitti, Ygghur from the set called Trilogy: Three Ages of Man.

The best tracks on this recording feature the Munich Chamber Orchestra, and especially on the longest track, for which the recording is named, Natura renovatur (for 11 strings, 1967). The typical Scelsi piece contains a basic kernel, a musical idea, that is developed for a short time. At over 12 minutes in this work, Scelsi actually goes beyond just discovering some little figure on his keyboard and creates a sustained work, with formal characteristics. The title may give us a clue as to what was on his mind: it comes from a phrase quoted often by alchemists, about nature being made new through fire. The image that the sounds of this performance conjures most often in my mind is that of something melting at high temperature. The other string ensemble works, Ohoi for 16 strings ("The creative principles") and Anâgâmin for 11 strings, make for nice listening, but I would not describe this disc as essential.

Frances-Marie Uitti will perform Scelsi's Trilogy -- the entire piece, of which one movement is found on this disc -- tomorrow night (June 21, 8 pm) at Columbia University's Italian Academy in Manhattan. One hour before the performance (7 pm), not to be missed, Ms. Uitti will hold a public discussion of Scelsi's music with Paul Griffiths. I am going to New York this weekend, but sadly not in time to catch this concert.

Giacinto Scelsi, Suite No. 10 (Ka) and No. 9 (Ttai), Markus Hinterhäuser, piano (released on January 25, 2005) |

Both suites are from the 1950s, slightly earlier than the works on the ECM disc. Suite No. 10 (1954) is given the title "Ka," the Egyptian word for life force. After death, the ka left the mortal body and in order to live in the afterlife, it needed a place like its body to dwell. Statues of the deceased were placed in the tomb for that purpose. Its seven brief movements set different moods according to the motifs that Scelsi received from the other world.

Suite No. 9 (1953) is subtitled "Ttai," a word whose origins are obscure to me. The commentary for this piece, which I suppose is Hinterhäuser's, gives us the following enlightening sentences: "A succession of [nine] episodes which alternately express Time -- or, more precisely, Time in motion -- and Man, as symbolized by cathedrals or monasteries, with the sound of the sacred 'Om'. This suite should be listened to and played with the greatest interior calm. Restless people should keep away." Reading that, I am compelled to think of the ridiculous and narcissistic "Buddhism" of the character Edina (Jennifer Saunders) on the British show Absolutely Fabulous:

Sweetie, you wouldn't say that if you knew how much we owe to my chanting, darling. Lots of things in this house, this HOUSE wouldn't be here, darling. I chanted for this gorgeous house. Chanted to be successful and believe in myself... Please, let me make some more money so I can buy Saffron some more books and a car... ting, ting, ting... In Buddhist, obviously, darling, when I do it properly.To a worse degree than the ECM disc, I found myself mostly tuning out. I am not saying that Scelsi's music is not worth listening to, only that it thrills me much less than I would prefer, at least in these two selections.

Saffron: What is it? Some sort of a cosmic cash machine?

UPDATE:

A review of Frances-Marie Uitti's recital at Columbia is in: Steve Smith, Frances-Marie Uitti Interprets Giacinto Scelsi’s ‘Trilogy’ (New York Times, July 24).

Listen to his stuff for large orchestra from the 60's. THAT's where Scelsi hit his stride.

ReplyDeleteDon't worry. I'm still listening. Thanks for the suggestion.

ReplyDeleteAgreed: pick up the disc with Aion/ Pfhat/ Konx-Om-Pax if at all possible. It's brilliant. It's more like early Ligeti with this surging, urgent tone that is just incredibly moving.

ReplyDeleteSorry to come so late to the post.

ReplyDeleteI've just began to come to terms with Scelsi's music recently, and it's the string quartets (5) that opened the door for me. Some critics think they're the summing-up of his oeuvre, and I agree.

The 2-CD set of the quartets (Arditti) is discontinued by now, but you might find the Auvidis reissue of the first Salabert edition in some shop. Worth trying.

Definitely, it's his works for large orchestra (with or without choir) that will blow your mind. There's nothing quite like it. The darkest passages of Penderecki/Ligeti/Holliger perhaps.

ReplyDeleteI've had his string quartets for a long time now - but hey, there's Bartok, Shostakovich. No mean guys to compete with in this setting.

I revaluated the quartets only after discovering Uaxuctum, and indeed, you might say it was all there right from the start