When the Baltimore Symphony Orchestra chose Yuri Temirkanov to succeed David Zinman (still fondly remembered in Baltimore and now hugely successful with his Zürich Tonhalle Orchestra), it went for a big name, seemingly eschewing controversy. Whether that worked out well is a matter of opinion. The orchestra has improved much in some sections and certain slices of repertoire – but has also pandered to popular taste with ‘safe’ programming (so infuriating Zinman that he resigned in protest from his position as conductor emeritus). During the Russian's time, audience numbers went down and the BSO’s financial situation worsened. Nor was Temirkanov, whose involvement and enthusiastic commitment seemed to leave something to be desired, controversy-free, either – especially towards the absence-marked end of his tenure. Last week he took his last bow as the BSO’s Music Director with a Mahler Second that must have been great on Thursday and very fine on Sunday but I thought oddly indifferent on Saturday.

When the Baltimore Symphony Orchestra chose Yuri Temirkanov to succeed David Zinman (still fondly remembered in Baltimore and now hugely successful with his Zürich Tonhalle Orchestra), it went for a big name, seemingly eschewing controversy. Whether that worked out well is a matter of opinion. The orchestra has improved much in some sections and certain slices of repertoire – but has also pandered to popular taste with ‘safe’ programming (so infuriating Zinman that he resigned in protest from his position as conductor emeritus). During the Russian's time, audience numbers went down and the BSO’s financial situation worsened. Nor was Temirkanov, whose involvement and enthusiastic commitment seemed to leave something to be desired, controversy-free, either – especially towards the absence-marked end of his tenure. Last week he took his last bow as the BSO’s Music Director with a Mahler Second that must have been great on Thursday and very fine on Sunday but I thought oddly indifferent on Saturday.In his succession, the BSO executives were bolder, courting controversy with their appointment of Marin Alsop (initially against the musicians’ will) as the new Music Director, making her the first female conductor of an orchestra of the BSO’s level of importance. Not coincidentally, it will also secure greater media coverage (and scrutiny) for the orchestra. That, along with forthcoming recordings (the Corigliano Violin Concerto, recorded from the Thursday, Friday, and Saturday performances this week, will be issued by Sony/BMG later this year while Alsop will continue her highly successful – publicity-wise, at any rate – connection with Naxos: a Dvořák cycle is going to be started with the BSO this year), will ensure far greater exposure and visibility for the BSO and presumably lead to more, greater contributions and perhaps even increased ticket sales. Perhaps Marin Alsop will prove such an able fundraiser – passively or actively – that she can even reclaim the weeks that will be cut from her orchestra’s schedule from next season on (assuming the orchestra is not cut down in size, instead). Judging from the excitement present Thursday evening, the BSO’s future may just look a bit brighter than many observers suspect or fear.

Tim Page, For Conductor Marin Alsop, An Expressive BSO Engagement (Washington Post, June 16) Tim Smith, Alsop enjoys smooth visit to BSO podium (Baltimore Sun, January 16) |

Rachmaninov’s Symphonic Dances, op. 45, is a younger work than the overture, having come late in Rachmaninov’s life. For that matter, the 1940 work is his last composition of significance. Fall and falling leaves in an ever-romantically wind-swept musical countryside, this music, written for Ormandy’s Philly Orchestra, has the distinct advantage over several other Rachmaninov works of being less concerned with squeezing every last tear out of the score but instead working with orchestral colors and mood. Winds excelled in the first movement (where an excellent alto sax, surrounded by clarinet chatter, and their assorted friends outdid themselves) that was momentarily turned into a wind symphony. Impressive, at least, how Marin Alsop led the BSO through the engaged, committed performance. The brass-plated finale with bells and whistles, crashes and thuds pulled all the bombastic stops from one of the finest bombast-composers. Temirkanov’s handwriting was obvious in the orchestra's playing; it is music that would have fitted well on one of his programs.

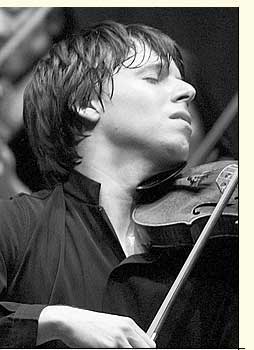

With an introduction to the concerto – replete with examples – Alsop managed to charm the audience while getting them ready to embrace John Corigliano’s “Red Violin” Violin Concerto. Starting over a gentle solo violin section quickly supported by flittering strings, occasionally soft woodwinds, the concerto allows the violinist – Joshua Bell – to meander about, which is exactly what the all-American sunny-boy of violinists did, in his own, somewhat peculiar style. Odd body movements, perhaps “illustrating” the music, drew more attention to himself than the music. Whether his playing suffered as a result was difficult to tell, especially as he was hard to hear whenever more than just wind and strings were playing in the orchestra. To be sure, I’ve never quite understood the fascination with Joshua Bell as a violinist – the son of a preeminent sexologist and psychotherapist, the late Alan Bell, hasn’t the most prodigious technique among his peers, nor a particularly supple or beautiful, much less a big tone. There are few works where I don’t see myself preferring another violinist – and if it be a household name, an American (perhaps even with a Baltimore connection), then Hilary Hahn obviously comes to mind as being a more interesting and, frankly, better violinist. In a recent game of contract switcheroo, Universal (DG) picked up Ms. Hahn, formerly Sony – and Sony signed Bell, formerly Universal (Decca). Bell sells obscene amounts of CDs (The Romantic Violin, Romance of the Violin, Violinistic Romanticism et al.) but in my book, Universal got a better deal by signing the superior artist.

With an introduction to the concerto – replete with examples – Alsop managed to charm the audience while getting them ready to embrace John Corigliano’s “Red Violin” Violin Concerto. Starting over a gentle solo violin section quickly supported by flittering strings, occasionally soft woodwinds, the concerto allows the violinist – Joshua Bell – to meander about, which is exactly what the all-American sunny-boy of violinists did, in his own, somewhat peculiar style. Odd body movements, perhaps “illustrating” the music, drew more attention to himself than the music. Whether his playing suffered as a result was difficult to tell, especially as he was hard to hear whenever more than just wind and strings were playing in the orchestra. To be sure, I’ve never quite understood the fascination with Joshua Bell as a violinist – the son of a preeminent sexologist and psychotherapist, the late Alan Bell, hasn’t the most prodigious technique among his peers, nor a particularly supple or beautiful, much less a big tone. There are few works where I don’t see myself preferring another violinist – and if it be a household name, an American (perhaps even with a Baltimore connection), then Hilary Hahn obviously comes to mind as being a more interesting and, frankly, better violinist. In a recent game of contract switcheroo, Universal (DG) picked up Ms. Hahn, formerly Sony – and Sony signed Bell, formerly Universal (Decca). Bell sells obscene amounts of CDs (The Romantic Violin, Romance of the Violin, Violinistic Romanticism et al.) but in my book, Universal got a better deal by signing the superior artist. All that is not to say that the redoubtable Mr. Bell did not perform his job amiably: he did. Balance problems such as Bell being drowned out at the end of the first movement can surely be adjusted over the next days, or, if need be and to the extent the score demands it, on the mixing table. The nervous second movement (Pianissimo Scherzo) with enthusiastic, obviously soft, percussion participation, sounds like music that desperately wished to bark but was kept on too short a leash or was simply too well behaved to do so. It ends with a little wink, courtesy of the triangle and soloist.

All that is not to say that the redoubtable Mr. Bell did not perform his job amiably: he did. Balance problems such as Bell being drowned out at the end of the first movement can surely be adjusted over the next days, or, if need be and to the extent the score demands it, on the mixing table. The nervous second movement (Pianissimo Scherzo) with enthusiastic, obviously soft, percussion participation, sounds like music that desperately wished to bark but was kept on too short a leash or was simply too well behaved to do so. It ends with a little wink, courtesy of the triangle and soloist.Andante Flautando, the third movement, is broad and rich – with the BSO coming up with a very pleasing, sonorous sound. Bell, meanwhile, is commanded by the composer to do more of the same; the effect is rather similar, if calmer, to the opening Chaconne. It all sounds like the muted parts of several Zbigniew Preisner scores strung together, and even the opening bursts of the Accelerando Finale cannot quite get rid of that impression. These quick bouts of speed merely sound hectic, the lyrical interpolations offer moments of beauty… but not always profundity. Here and there its origins as Film Music peek through.

From all this, I don’t quite understand how this work became the most performed violin concerto composed in the last quarter century. Such works by Philip Glass and John Adams do more for me, as does another BSO commission (the constant commission of new pieces, it must be said, is one of the BSO’s most commendable characteristics), the Brubaker violin concerto, which I thought a small masterpiece. At least I find it reassuring that Corigliano’s own superb Of Rage and Remembrance is performed more often than the “Red Violin Concerto.” The crowd in the very well-filled Meyerhoff Hall obviously felt otherwise; perhaps stirred by the sense of occasion they received the performance and performers thunderously with enthusiastic and lasting standing ovations.

Repeat performances will take place today, Friday, at 8PM, and tomorrow, Saturday, at 11AM (without the Rachmaninov).