In a wise, anticipatory move, Amtrak and Marc trains run as if their funding had already been taken away. It will guarantee a smooth transition for when the time comes and it was – despite unmasked incompetence in running a proper public transportation system – good enough to dump me at the steps of the Meyerhoff Hall in Baltimore just a few minutes after Vadim Repin and Nikolai Lugansky were supposed to have started their recital. Simultaneously, if from different ends, the two musicians and I walked into a Meyerhoff Hall so empty, it suggested us having showed up there far too early. With a recital of two of the world’s premiere artists (indeed Repin arguably the finest violinist of his generation and just last week signed on as an exclusive Deutsche Grammophone artist), the concert hall was shamefully empty; less than half full. I am not sure if that sorry state says more about the support for the arts in Baltimore in general, or Baltimore’s lack of a more appropriate venue for a recital, or an abysmal failure on the BSO’s part (which featured the concert) to adequately promote this event. Probably a mix of all of the above.

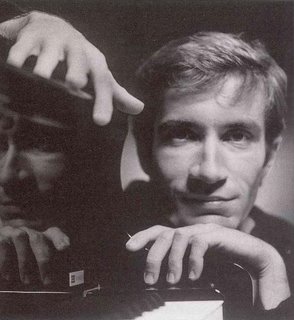

In a wise, anticipatory move, Amtrak and Marc trains run as if their funding had already been taken away. It will guarantee a smooth transition for when the time comes and it was – despite unmasked incompetence in running a proper public transportation system – good enough to dump me at the steps of the Meyerhoff Hall in Baltimore just a few minutes after Vadim Repin and Nikolai Lugansky were supposed to have started their recital. Simultaneously, if from different ends, the two musicians and I walked into a Meyerhoff Hall so empty, it suggested us having showed up there far too early. With a recital of two of the world’s premiere artists (indeed Repin arguably the finest violinist of his generation and just last week signed on as an exclusive Deutsche Grammophone artist), the concert hall was shamefully empty; less than half full. I am not sure if that sorry state says more about the support for the arts in Baltimore in general, or Baltimore’s lack of a more appropriate venue for a recital, or an abysmal failure on the BSO’s part (which featured the concert) to adequately promote this event. Probably a mix of all of the above. For those who were there (mostly Russians, not surprisingly), Repin and Lugansky had assembled an interesting and perhaps even daring program, opening with Bartók’s Rhapsodie no.1. The first movement (Moderato/Lassú) was square and boxy, angular and precise. The Allegretto moderato / Friss turned on a dime into something much more intimate and sparkling. The work lived off these stark contrasts so well accentuated. Like the following Schubert Fantasia in C-major D934 (a svelte, dancing performance!) the Bartók was lost in the too-large space of the hall. The intimacy and detail that make Repin’s play so special did not quite make it beyond the first block of seats. At a greater disadvantage still was his partner Lugansky who was reduced to plinking about for much of the concert, trying to find a suitable medium between filling the hall with a round sound and not overbearing Repin. It says much about the two artists’ seemingly infinite technical and musical resources that the result was so impressive and felt despite the adverse circumstances.

For those who were there (mostly Russians, not surprisingly), Repin and Lugansky had assembled an interesting and perhaps even daring program, opening with Bartók’s Rhapsodie no.1. The first movement (Moderato/Lassú) was square and boxy, angular and precise. The Allegretto moderato / Friss turned on a dime into something much more intimate and sparkling. The work lived off these stark contrasts so well accentuated. Like the following Schubert Fantasia in C-major D934 (a svelte, dancing performance!) the Bartók was lost in the too-large space of the hall. The intimacy and detail that make Repin’s play so special did not quite make it beyond the first block of seats. At a greater disadvantage still was his partner Lugansky who was reduced to plinking about for much of the concert, trying to find a suitable medium between filling the hall with a round sound and not overbearing Repin. It says much about the two artists’ seemingly infinite technical and musical resources that the result was so impressive and felt despite the adverse circumstances.A. Pärt, Fratres (Violin & Piano and Cello versions), Tabula Rasa, Benjamin Britten Cantus, Gidon Kremer, Keith Jarrett, Alfred Schnittke / Russell Davies |

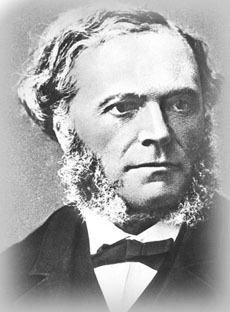

The César Franck sonata is popular and rightly so, if perhaps not for the reasons I deem it great. It’s a work by a 64 year old man never known for any revolutionary sentiment or affect. And yet here he very quietly delivers a sublime work that just as quietly undercuts all convention, that is far ahead of its time while sounding conservative enough on the surface to placate the romantic-music denizens helplessly stuck in their arrested development.

The César Franck sonata is popular and rightly so, if perhaps not for the reasons I deem it great. It’s a work by a 64 year old man never known for any revolutionary sentiment or affect. And yet here he very quietly delivers a sublime work that just as quietly undercuts all convention, that is far ahead of its time while sounding conservative enough on the surface to placate the romantic-music denizens helplessly stuck in their arrested development.With unusual rhythm, unusual mood and flaunting its assigned key more often than heeding to it, the first movement – and indeed the entire sonata – takes (secret) leave of standard form. Yet it never does so with the academic obstinance as so much of modern music deliberately did and does. It charms. Instead of robbing the listeners of their expectations at gun point, it smiles, teary-eyed, and – before they ever know it – manages to have stolen their wallet. And most beguiling as she is (clearly a female sonata; even in its stormy passion full of grace) we listeners don’t even mind when we find out that she stole our heart, too. And all because she is solidly modern under a romantic coat.

Repin and Lugansky clearly did something right to have elicited that much emotion in the first place. Even if that could not quite make up for the fact that too much music became a wash in the venue, it had the sparse audience leap to their feat and applaud and cheer loud enough for all those absent-twice over, absolutely forcing the boys to give two encores. But then, they were playing to a home crowd.