|

|

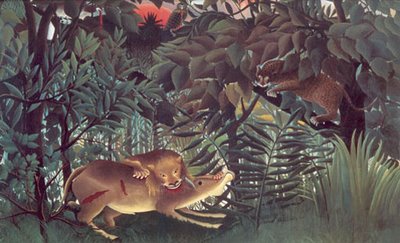

What did Rousseau study when he painted those tropical plants and those jungle animals? He modeled his work on the plant exhibits and the Ménagerie (zoo) at the Jardin des Plantes, as well as illustrated books, magazines, and postcards that had images from it, and the taxidermic dioramas of wild animals at the Muséum d'Histoire naturelle. On the middle floor, there is one such diorama from that museum, a lion attacking a gazelle, which one can compare to a roomful of the jungle scenes with animals, including Le lion ayant faim se jette sur un antélope (1905), which is shown here. When you see these images juxtaposed, suddenly some of the artificiality in Rousseau's work, which so appealed to the Surrealists, makes sense. The same is true of the plants, which are so similar in all of the paintings: he may have seen alive but that he probably painted from postcard or magazine images.

For most of his life, Rousseau was not a full-time painter. He had a career as a city employee, working in an octroi, one of the customs posts at the edge of Paris that imposed a tax on merchandise imported into the city. (This is where he got the nickname Douanier, or customs agent, to distinguish him from the famous Enlightenment writer of the same last name.) Apparently, as there were sometimes long waits at the lonely station, he painted at work and even made a portrait of his post (shown at right). In this way, he was also a documenter of Parisian scenes, as he set up his easel around the city, in roughly the same period as Eugène Atget was making his photographic map of Paris. In fact, the exhibit includes some photographs from this period, including Atget's Porte d'Arcueil (bd. Jourdan), a shot of an octroi post from 1913, which is more or less identical with the one where Rousseau worked, at the Porte de Vanves. (The two portes, or gates into the city, are not far from one another, to the south, at the edge of the 14th arrondissement.)

For most of his life, Rousseau was not a full-time painter. He had a career as a city employee, working in an octroi, one of the customs posts at the edge of Paris that imposed a tax on merchandise imported into the city. (This is where he got the nickname Douanier, or customs agent, to distinguish him from the famous Enlightenment writer of the same last name.) Apparently, as there were sometimes long waits at the lonely station, he painted at work and even made a portrait of his post (shown at right). In this way, he was also a documenter of Parisian scenes, as he set up his easel around the city, in roughly the same period as Eugène Atget was making his photographic map of Paris. In fact, the exhibit includes some photographs from this period, including Atget's Porte d'Arcueil (bd. Jourdan), a shot of an octroi post from 1913, which is more or less identical with the one where Rousseau worked, at the Porte de Vanves. (The two portes, or gates into the city, are not far from one another, to the south, at the edge of the 14th arrondissement.)Gertrude Stein, in The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas (read the review that Edmund Wilson wrote in 1933), wrote about her maid Helene's surprise that the painters who frequented her employer's salon were becoming famous:

To her great regret she left and later she always said that life at home was never as amusing as it had been at the rue de Fleurus. Much later, only about three years ago, she came back for a year, she and her husband had fallen on bad times and her boy had died. She was as cheery as ever and enormously interested. She said isn't it extraordinary, all those people whom I knew when they were nobody are now always mentioned in the newspapers, and the other night over the radio they mentioned the name of Monsieur Picasso. Why they even speak in the newspapers of Monsieur Braque, who used to hold up the big pictures to hang because he was the strongest, while the janitor drove the nails, and they are putting into the Louvre, just imagine it, into the Louvre, a picture by that little poor Monsieur Rousseau, who was so timid he did not even have courage enough to knock at the door.

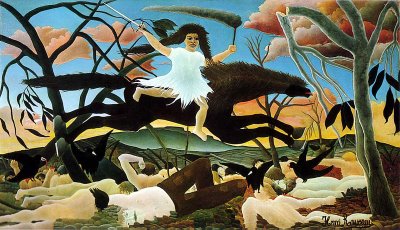

Shortly before Rousseau died, Guillaume Apollinaire and Pablo Picasso organized a famous banquet in Rousseau's honor, which Gertrude Stein also described. It included spontaneous -- mostly drunken -- musical performances, singing by Marie Laurencin, Ms. Stein and Ms. Toklas, and violin solos by the intensely shy dounanier Rousseau himself. In a drunken moment of excess, André Salmon tried to eat Alice Toklas's new hat. It was a legendary party. Rousseau was a modernist without intending to be so. The exhibit has a number of his most famous paintings, including La guerre (1894), one of the most profound visual statements about the scourge of war, up there with Picasso's Guernica, the collective Peace Tower, and others. The imagery -- the subtitle is "the horseride of Discord" -- is probably based on Rousseau's memories of the Franco-Prussian War and the brief domination of the Paris Commune, conflicts that had severely shaken up many Parisians 20 years earlier.

Shortly before Rousseau died, Guillaume Apollinaire and Pablo Picasso organized a famous banquet in Rousseau's honor, which Gertrude Stein also described. It included spontaneous -- mostly drunken -- musical performances, singing by Marie Laurencin, Ms. Stein and Ms. Toklas, and violin solos by the intensely shy dounanier Rousseau himself. In a drunken moment of excess, André Salmon tried to eat Alice Toklas's new hat. It was a legendary party. Rousseau was a modernist without intending to be so. The exhibit has a number of his most famous paintings, including La guerre (1894), one of the most profound visual statements about the scourge of war, up there with Picasso's Guernica, the collective Peace Tower, and others. The imagery -- the subtitle is "the horseride of Discord" -- is probably based on Rousseau's memories of the Franco-Prussian War and the brief domination of the Paris Commune, conflicts that had severely shaken up many Parisians 20 years earlier. There are plenty of those strangely barren landscapes that strike us as similar to Surrealism, too. One I had never known before and really liked, for its quality of medieval pageantry, was La Liberté invitant les artistes à prendre part à la 22ème exposition des indépendants (1906), now in a museum in Tokyo. There is a whole room of gorgeous landscapes, mostly small-format canvases that show scenes of Paris. His paintings of people are no less surreal, including the famous self-portrait, Myself, Portrait-Landscape (1890). The two portraits of women look remarkably akin to Frida Kahlo's stiff self-portraits. Also, La Promenade dans la forêt (c. 1886, now in Zurich) has a paranoid quality that reminded me of Max Ernst's 2 enfants sont menacés par un rossignol. Another favorite was the sphinxian Portait de Monsieur X (c. 1910, now in Zurich), showing a man now identified as novelist Pierre Loti.

This exhibit was at the Tate Modern in London (November 3, 2005, to February 5, 2006) and will come to the National Gallery of Art here in Washington this summer (July 16 to October 15).

It is freaky to see the Lion/Gazelle that R. (who I have always intensely disliked, as a painter) painted so suddenly be so realistic, after all. Still, the two dimensional, flat, naive or faux-naive (does it matter?) style annoyed me, because it always reminded me of similar scenes we were made to paint in school - with the demand to fill out the entire A2 format paper. Big green leaves and absence of the third dimension were key! Rousseau - not Rothko or Pollock or Newman - have ever since represented to me the "Hey, I could do that" type of painter. (Even if, admittedly, I could decidedly NOT paint like Rousseau. [I wish I could, although if I could, I'd still think I suck.]

ReplyDeleteNo you don't jfl, come on, chin up. I would rather see this in Paris, but DC will do just fine. Is that near Baltimore?

ReplyDelete