There are good concerts, there are excellent ones, and there are life-altering ones. Friday evening's free concert at the Library of Congress was one of the latter, the perfect combination of stellar performers and a killer program. This was, sad to say, the first true high point of what has been a somewhat tepid season at the Library, by comparison to previous ones. Tenor Ian Bostridge joined forces with his frequent accompanist, Julius Drake, and the always strong Belcea Quartet in a program that included the Shostakovich third string quartet, as well as two song cycles accompanied by piano and string quartet. Not surprisingly, the legendary Coolidge Auditorium was nearly full, although there were still a few empty seats here and there, meaning that no one who showed up without a reserved place was turned away.

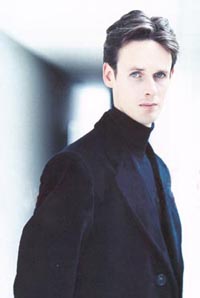

There are good concerts, there are excellent ones, and there are life-altering ones. Friday evening's free concert at the Library of Congress was one of the latter, the perfect combination of stellar performers and a killer program. This was, sad to say, the first true high point of what has been a somewhat tepid season at the Library, by comparison to previous ones. Tenor Ian Bostridge joined forces with his frequent accompanist, Julius Drake, and the always strong Belcea Quartet in a program that included the Shostakovich third string quartet, as well as two song cycles accompanied by piano and string quartet. Not surprisingly, the legendary Coolidge Auditorium was nearly full, although there were still a few empty seats here and there, meaning that no one who showed up without a reserved place was turned away.This British Dream Team of musicians first gave us the delicious song cycle On Wenlock Edge (1908/09), composed for this combination by Ralph Vaughan Williams. The texts are six poems from A. E. Housman's A Shropshire Lad, one of the best collections of poetry from a single author ever, in my opinion. I wish that Vaughan Williams had set the entire book as a single cohesive work. Judging from what he did with just these six poems, the result would have been superlative. The Belcea Quartet added sounds, hues, atmosphere to the nostalgic words, like the thrashing gale in the first song, On Wenlock Edge, first in the whirring opening and later in creepy, near-the-bridge playing. Vaughan Williams divides the instruments in the third song, Is My Team Ploughing, to characterize the two characters in dialogue differently. In the same way, Bostridge used his unusual voice, often ethereal, to create the sense of conversation. This English tenor is the quintessential "intelligent singer," quite literally, given that Dr. Bostridge holds a doctorate from Oxford. His voice may not bowl one over with power, but few sing with more understanding and musical intelligence.

The best song of the Vaughan Williams was the fifth one, Bredon Hill, accompanied by hushed, glassy chords in the strings, punctuated by piano, evoking the distant sound of "The bells they sound so clear." Whereas in some of the louder textures, Bostridge's voice was sometimes covered by his colleagues, here his pure tenor and soft high notes had the perfect sonic envelope for an exquisite sung recitation of this poem. For me, the effect was emotionally overwhelming as the strings began to strike the ostinato of the single funeral bell, rung at the death of the man's beloved. When the narrator has to hear that opening bell theme again, Bostridge captured the tone of mute bitterness in Housman's line, "O noisy bells, be dumb; / I hear you, I will come."

The best song of the Vaughan Williams was the fifth one, Bredon Hill, accompanied by hushed, glassy chords in the strings, punctuated by piano, evoking the distant sound of "The bells they sound so clear." Whereas in some of the louder textures, Bostridge's voice was sometimes covered by his colleagues, here his pure tenor and soft high notes had the perfect sonic envelope for an exquisite sung recitation of this poem. For me, the effect was emotionally overwhelming as the strings began to strike the ostinato of the single funeral bell, rung at the death of the man's beloved. When the narrator has to hear that opening bell theme again, Bostridge captured the tone of mute bitterness in Housman's line, "O noisy bells, be dumb; / I hear you, I will come."Bernard Holland, Ephemeral But Powerful, With Tinges of France (New York Times, March 15) Alex Ross, Songs of Experience (The New Yorker, March 27) Alex Ross, Britten Notes (The Rest Is Noise, March 22) |

| Available at Amazon: Songs of Fauré, Debussy, Poulenc, Ian Bostridge, Belcea Quartet, Julius Drake, Leon Bosch (released on November 2, 2004) |

The technical crew may have been off their game, which is unusual for this most refined of venues. First, the concert was delayed briefly while page-turner Elmer Booze waited for a chair to be placed next to the piano. They also replaced the cellist's chair with a different model after the first piece, and for some reason the house lights were never lowered. (For the vocal selections, this allowed listeners to consult their programs for the song texts -- which they did, with much rustling of pages -- but why during the Shostakovich?) Through the stage door, left slightly ajar, we were able to see the performers hugging one another, visibly moved and happy, after the Fauré. Judging by the ovations each piece received, the audience clearly shared their enjoyment.

Bostridge and Drake were just in New York on Wednesday, for a Britten concert with other musicians at Zankel Hall (see Anthony Tommasini's review for the New York Times and Jay Nordlinger's review for the New York Sun, both published on March 10). Bostridge has planned a whole series of recitals in New York over the next couple months, and he will present this program in Zankel Hall tonight with the same group of musicians. Get there, New Yorkers!

No comments:

Post a Comment