G.Bizet/J.Serebrier, Carmen Symphony, J.Serebrier / OS Barcelona BIS     |

Speaking of Serebrier, he is a phenomenon unto himself. He must easily be the most successful, most award-winning, most often recorded unknown conductor (and composer). Even in the U.S., the home of most of his success. Perhaps it is different in his native Uruguay. The apprentice of Anatol Dorati, the assistant conductor to Leopold Stokowski (who sent Serebrier into his career proclaiming him “the greatest master of orchestral balance”), 1968 winner of the Ford Foundation American Conductors Award, with over 250 recorded CDs and 33 Grammy nominations (including a Latin Grammy award for best classical album – which strikes me as somewhere between odd and insulting, actually) – and somehow he would not likely make it onto most casual music lovers’ list if they were asked to produce some of the great living conductors (active in America) or composers. Perhaps he is not limelight-seeking enough, perhaps he is neither enough fish (conductor) or fowl (composer) to corner wide popular acknowledgement in either field, perhaps he composed music too tonal, too early. (He actually provided a partial answer on Monday when he introduced a 1965 National Education Television program that showed the premiere of Ives’s fourth symphony, in which he was involved: When Leopold Stokowski first tried to premiere the Ives, he didn’t get beyond the first bar and lacked enough time for rehearsal. Instead of doing Ives, he called upon the 19-year-old Serebrier to have the latter’s first symphony premiered. A long interview with Time Magazine followed and other media attention was assured; alas, the night his symphony premiered, Sputnik was launched into space and occupied the news for the next weeks. The interview in Time never ran. Serebrier’s fame was postponed.)

Speaking of Serebrier, he is a phenomenon unto himself. He must easily be the most successful, most award-winning, most often recorded unknown conductor (and composer). Even in the U.S., the home of most of his success. Perhaps it is different in his native Uruguay. The apprentice of Anatol Dorati, the assistant conductor to Leopold Stokowski (who sent Serebrier into his career proclaiming him “the greatest master of orchestral balance”), 1968 winner of the Ford Foundation American Conductors Award, with over 250 recorded CDs and 33 Grammy nominations (including a Latin Grammy award for best classical album – which strikes me as somewhere between odd and insulting, actually) – and somehow he would not likely make it onto most casual music lovers’ list if they were asked to produce some of the great living conductors (active in America) or composers. Perhaps he is not limelight-seeking enough, perhaps he is neither enough fish (conductor) or fowl (composer) to corner wide popular acknowledgement in either field, perhaps he composed music too tonal, too early. (He actually provided a partial answer on Monday when he introduced a 1965 National Education Television program that showed the premiere of Ives’s fourth symphony, in which he was involved: When Leopold Stokowski first tried to premiere the Ives, he didn’t get beyond the first bar and lacked enough time for rehearsal. Instead of doing Ives, he called upon the 19-year-old Serebrier to have the latter’s first symphony premiered. A long interview with Time Magazine followed and other media attention was assured; alas, the night his symphony premiered, Sputnik was launched into space and occupied the news for the next weeks. The interview in Time never ran. Serebrier’s fame was postponed.)With the National Gallery Orchestra (which seems to be growing from performance to performance), the troublesome acoustic of the West Garden Court, and all-Strauss, I wasn’t expecting too much from the first half – but was proven wrong entirely. First of all, my “there-is-only-one-Strauss-and-his-name-doesn’t-start-with-a-‘J’” attitude is part charade: Johann Strauss’s music does the soul good from time to time; aside, it reminds me of home. Secondly, the National Gallery Orchestra’s very good, precise, and engaged playing – in itself often cause for joy that night – actually sounded pretty good with the super-reverb added from the hall. For one, it made the orchestra seem twice as large than it already is. Sure, it didn’t exactly allow analytical insights into the music with the lush and dense sound produced, but it packed a punch and impressed: a good combination with the Strauss. The non-Strauss interruption of the first half – wedged between Fledermaus overture, Kaiser-Waltzer, Pizzicato-Polka, and Tritsch-Tratsch-Polka – was the thunderously played waltz out of Spyashchaya krasavitsa which rolls more easily off our tongues as “Sleeping Beauty.”

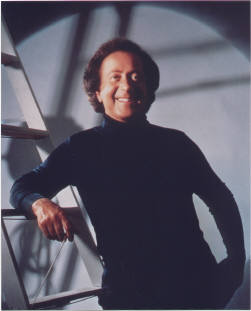

After the greatly enjoyable first half, I looked forward to what had initially attracted me to the concert: Serebrier’s own compositions and arrangements. The conducting composer, who looks a bit like a jolly (but classy) Richard Simmons, gave the U.S. premieres of his 2001 and 2002 compositions Tango in Blue and Casi un Tango. Whereas the mono-melodious Strauss had not suffered (if anything, benefitted) from the acoustic, Tango in Blue got lost in it. One of several short tangos Serebrier composed over the last years, it is a short, ebullient orchestral work with piano that has the entire band dance several tangos with and against each other. I can see how it would make for great encore and fanfare calling cards for Serebrier himself or indeed any orchestra playing tango- or South America-related programs. Casi un Tango was thinner, more lyrical, contemplative - and the high, unisono violin parts often challenged the NGO’s string section while the lamenting cor anglais was unnecessarily out of tune. It struck me as a music that chose a complicated way of saying something simple.

As for Jacob Gade’s (1869-1963) Jalousie from 1936, I have not heard about, but I have certainly heard it before. As a soundtrack to a movie perhaps? It was most agreeable… like sophisticated Henry Mancini, perhaps. Had it not been translated as “Jealousy” in the notes, I would have thought that it was about (window) blinds. Oblivion by Astor Piazzolla was heavenly – assuming a liking of the bandoneon, so expertly and passionately handled by Raul Jaurena. This square, German/Argentine cousin of the accordion that can fold out forever (it only plays when pulled apart and has to be folded together quickly before continuing; as if to catch its breath) has an immediately recognizable sound that is charming, seductive, and mournful all in one. The reaction of the generally very excited crowd, too, declared this contribution unanimously their favorite. Georges Bizet composed the last work on the program, Farandole, taken from the Suite Arlésienne. Serebrier, who led it to a rousing finish, should know Bizet very well; he recently recorded his own arrangement of the Carmen music in a highly acclaimed CD titled “Carmen Symphony” on BIS.

As for Jacob Gade’s (1869-1963) Jalousie from 1936, I have not heard about, but I have certainly heard it before. As a soundtrack to a movie perhaps? It was most agreeable… like sophisticated Henry Mancini, perhaps. Had it not been translated as “Jealousy” in the notes, I would have thought that it was about (window) blinds. Oblivion by Astor Piazzolla was heavenly – assuming a liking of the bandoneon, so expertly and passionately handled by Raul Jaurena. This square, German/Argentine cousin of the accordion that can fold out forever (it only plays when pulled apart and has to be folded together quickly before continuing; as if to catch its breath) has an immediately recognizable sound that is charming, seductive, and mournful all in one. The reaction of the generally very excited crowd, too, declared this contribution unanimously their favorite. Georges Bizet composed the last work on the program, Farandole, taken from the Suite Arlésienne. Serebrier, who led it to a rousing finish, should know Bizet very well; he recently recorded his own arrangement of the Carmen music in a highly acclaimed CD titled “Carmen Symphony” on BIS.Of course no New Year’s concert could be finished without the Donau-Waltzer, and that blue Danube encore did delight under the continuously high-energy, joyful leadership of the conductor. Better still was the return of Mr. Jaurena for an encore and finally there was the wild clap-along of the Radetzky-Marsch where Serebrier pulled all stops and sent the crowd home happy. And a happy start into the 2006 part of the concert season it was, indeed.