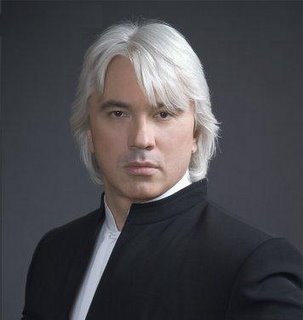

One of the advantages of hearing a string of choruses and arias of Russian operas is the convenient fact that you can enjoy music of some of the more (and rightly so) obscure operas of Rimsky-Korsakov, Rachmaninov, and Rubinstein without having to sit through the whole thing. Also, you get a year's supply of "Slava-Slava" slapped around your ears. In the chorus of the "Procession of the Nobles" from the Rimsky-Korsakov opera Mlada my ‘slava-counter’ broke down at 27. All that before Dmitri Hvorostovsky had even taken the stage on Wednesday at the Kennedy Center’s Concert Hall.

One of the advantages of hearing a string of choruses and arias of Russian operas is the convenient fact that you can enjoy music of some of the more (and rightly so) obscure operas of Rimsky-Korsakov, Rachmaninov, and Rubinstein without having to sit through the whole thing. Also, you get a year's supply of "Slava-Slava" slapped around your ears. In the chorus of the "Procession of the Nobles" from the Rimsky-Korsakov opera Mlada my ‘slava-counter’ broke down at 27. All that before Dmitri Hvorostovsky had even taken the stage on Wednesday at the Kennedy Center’s Concert Hall.The Russian

Moscow Nights, Hvorostovsky / Orbelian Delos     |

“Na vozdushnom oceane” from the same work followed – a most pleasant, lyrical and sweeping passage where baritone, orchestra, and pianist can indulge in melody and more long-held notes that never miss their desired effect. It reminds why Rubinstein’s second symphony is rightly among the more popular of the obscure Russian symphonic works. Perky (or, more honestly, coarse) woodwinds from the Constantine Orbelian-led Philharmonia of Russia jolted the gorgeous and usually calm prelude from Khovanshchina (Mus

Charles T. Downey, Dmitri Hvorostovsky, Rock Star (DCist, January 19) Tim Page, From Russia With Love and Patriotism (Washington Post, January 20) |

The Shostakovich waltz from his film music to “The First Echelon” is anonymously famous. I certainly have never seen that film but the music is hum-along familiar; seemingly the soundtrack to every film where the director wants music that says “Russia.” Although catchy, it’s a reminder that DSCH was not above writing the occasional piece of awful and trite schlock. Allegedly it was Shostakovich’s film music that kept the composer in Stalin’s more-or-less good graces for many years. If true, it is proof that, apart from having attained a secure spot in the triumvirate of 'most horrendous leaders in world history', he also had bad taste. Nothing sours me as much as standing on a heap of 50 million-plus rotten corpses and having a deficient aesthetic.

Noodling off a couple more tearjerkers (if I were Russian, I would have been a sobbing mess, too – I know too well how I react to Bavarian and Austrian folk fare when it smells of Heimat), Hvorostovsky had the audience eating out of his hand. That he was miked for these songs was the necessary compromise of not wanting to have to belch these songs out like opera arias but still being heard in the last rows of the filled hall. Along with him, the Russian folk-instrument ensemble "Style of Five" provided some authentic sounds with bayan (accordion), balalayka, and a balalayka cousin of Mongolian origin, the three-string domra.

Noodling off a couple more tearjerkers (if I were Russian, I would have been a sobbing mess, too – I know too well how I react to Bavarian and Austrian folk fare when it smells of Heimat), Hvorostovsky had the audience eating out of his hand. That he was miked for these songs was the necessary compromise of not wanting to have to belch these songs out like opera arias but still being heard in the last rows of the filled hall. Along with him, the Russian folk-instrument ensemble "Style of Five" provided some authentic sounds with bayan (accordion), balalayka, and a balalayka cousin of Mongolian origin, the three-string domra.Although the chorus’s contribution was well received, I imagine that a Russian Choir might have brought more to the performance than the timid Cathedral Chorus Society’s singing. That full, sonorous and ringing tone was never even approximated. Three encores of the most loved and famous of these “War Songs,” “Katyusha,” “Podmoskovnye Vechera” (Moscow Nights), and “Ochi Chernye” (Dark Eyes), brought the swooning crowd to their feet. Then Elvis Hvorostovsky left the building; alas, not before signing CDs to excited hordes of fans.