I Hear America, Part I I Hear America, Part II I Hear America, Part III |

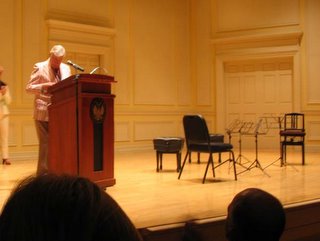

Before the Jupiter Quartet’s concert at the Library of Congress, it was Gunther Schuller’s turn to be honored by the Library of Congress. Apparently America had heard him - and liked what it had heard – and the fresh octogenarian was named a Library of Congress Living Legend. About the medal he received, Schuller said, “Oh, this will go nicely with my twelve honorary doctorates.” That somewhat ambiguous response made for a ripple of laughter before his very short acceptance speech clarified that he was indeed grateful to the Library.

Then rolled out the four string players who had so impressed me with their performances of the second Britten Quartet at the Corcoran Gallery (October 21st, Ionarts review here). The slowly awakening theme of the first movement (Allegro con spirito) in Haydn’s quartet, op. 76, no. 4, gave the work its English nickname, “Sunrise.” The Jupiter Quartet’s first violinist, Nelson Lee, soared above his three colleagues Meg Freivogel (second violin), David McDonough (cello), and Liz Freivogel (viola). I don’t go to the Library of Congress very often anymore, but when I do it is for a good reason. This time I wanted to check up on the viola playing of the Freivogel sister, wondering if the concert at the Corcoran where she had stood out among already excellent performers (including Roger Tapping) and amazed me with a stupendous viola sound, had been a fluke or not.

Playing at the LoC, they were now fitted with different instruments, the library's own Stradivarii: the 1704 “Betts” violin for Meg, the “Castelbarco” violin and cello for Messrs. Lee and McDonough, respectively, and the “Cassavetti” viola (from Stradivari’s golden period – 1727). With an instrument like that, it should have seemed easier yet for the violist to make a splendid sound and easier for me to decide whether to laud her playing, her own instrument, or the Corcoran Gallery’s acoustic for the previous enchantment.

Playing at the LoC, they were now fitted with different instruments, the library's own Stradivarii: the 1704 “Betts” violin for Meg, the “Castelbarco” violin and cello for Messrs. Lee and McDonough, respectively, and the “Cassavetti” viola (from Stradivari’s golden period – 1727). With an instrument like that, it should have seemed easier yet for the violist to make a splendid sound and easier for me to decide whether to laud her playing, her own instrument, or the Corcoran Gallery’s acoustic for the previous enchantment.Amid the well-executed but unremarkable Haydn and seated next to the booming, noisy (gloriously noisy, if you wish) Castelbarco cello, she did not stand out with the new instrument which seemed timid and chorister-voiced compared to my memory of the last concert. Interestingly enough, Mr. McDonough pointed out that a good number of violists that come through the Library end up choosing their own instrument over the small Strad viola – something I readily believed after hearing (or rather, not hearing) Liz Freivogel disappear sonically. I don’t know how hard she has to work on her regular instrument to get it to sound good – but however hard that may be, it’s worth it as far as I, the listener, am concerned.

Dutilleux again after a recent run-in at La Maison Française. Ainsi la nuit and its seven movements are a Koussevitzky Foundation commission (of which Mr. Schuller is the President) and turned out to be a very busy, percussive, and long piece which was good to hear but didn’t catch me either with or in the mood to heed in the way that Trois strophes sur le nom de Sacher had. Schubert’s Death and the Maiden (D810) opened with all the stringent force the Jupiter players could get out of their instruments. The work's beauty can come out in as many interpretive approaches as there are to it. Including the aggressive, nervously jittering way this young foursome opted for. Especially the Allegro, the first movement, was now a show of brilliance; very much ‘in your face’. Short on Viennese languor and devoid of the confident sweetness I missed in it, D.810 turned out more self-conscious than I would prefer to listen to on a regular basis. There is more interpretive depth to be found in this masterpiece even if, for now, it seemed valid enough to brush interpretive complacency aside and err (if err they did) on the side of wild, youthful vigor, even mawkishness. In all that drive, a few squeaks were inevitable. The haunting beginning of the Andante con moto, by the way, was marvelous; it hung in the room as though permanently suspended. The viola was still near inaudible. The blazing Presto energized the crowd. Their excitement (standing ovations, of course) was perhaps more than I expected. But it brought them back for the Intermezzo from Mendelssohn’s A minor quartet, op. 13. For a brief solo moment I heard the viola, too. I wish I hadn’t.

Dutilleux again after a recent run-in at La Maison Française. Ainsi la nuit and its seven movements are a Koussevitzky Foundation commission (of which Mr. Schuller is the President) and turned out to be a very busy, percussive, and long piece which was good to hear but didn’t catch me either with or in the mood to heed in the way that Trois strophes sur le nom de Sacher had. Schubert’s Death and the Maiden (D810) opened with all the stringent force the Jupiter players could get out of their instruments. The work's beauty can come out in as many interpretive approaches as there are to it. Including the aggressive, nervously jittering way this young foursome opted for. Especially the Allegro, the first movement, was now a show of brilliance; very much ‘in your face’. Short on Viennese languor and devoid of the confident sweetness I missed in it, D.810 turned out more self-conscious than I would prefer to listen to on a regular basis. There is more interpretive depth to be found in this masterpiece even if, for now, it seemed valid enough to brush interpretive complacency aside and err (if err they did) on the side of wild, youthful vigor, even mawkishness. In all that drive, a few squeaks were inevitable. The haunting beginning of the Andante con moto, by the way, was marvelous; it hung in the room as though permanently suspended. The viola was still near inaudible. The blazing Presto energized the crowd. Their excitement (standing ovations, of course) was perhaps more than I expected. But it brought them back for the Intermezzo from Mendelssohn’s A minor quartet, op. 13. For a brief solo moment I heard the viola, too. I wish I hadn’t.